Children and violence: an introductory, international and interdisciplinary approach

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 14 May 2024, 12:11 AM

Children and violence: an introductory, international and interdisciplinary approach

Introduction

Children are subject to many forms of adversity, for example, poverty or ill health. However, a significant form of adversity experienced by children in many different regions of the world is violence. The form of violence against children varies widely and is hugely disparate. In this course, the focus is on three different environments where children experience violence: at home, among peers at school and in the wider society (in the context of armed conflicts). The text considers the experiences of children both locally and globally. For this reason, violence against children should not be considered a phenomenon that is remote. Sadly, children may experience violence in their families and among their peers, and may also become involved in armed conflict. The course considers in detail the daily experiences of violence which can have negative impacts on the physical or emotional health of children and moves from ideas about children and violence in very localized contexts – within families and with peers at school – through to the broader community and on to the international perspective. It also analyses the different roles that children take on in relation to violence, such as victim, perpetrator, witness, colluder and peacemaker.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in People, Politics & Law.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

discuss the ways in which children are the victims of violence and the multiple effects that violence has on children, encompassing not only physical pain and injury but also psychological damage

examine the various roles that children play in relation to violence, as victims, perpetrators, witnesses, colluders and peacemakers

analyse the relationship between children as victims of violence and as perpetrators of violence

analyse the role of children in armed conflicts and discuss why children are not only victims in war

examine the ways in which children and their communities have attempted to end violence in their lives.

1 Overview

1.1 Children and violence

Children are subject to many forms of adversity, for example, poverty or ill health. This course examines another form of adversity that many children face, namely violence. This is a huge topic which can be tackled in a number of ways, for example by looking at the effects of war on children in Africa and Asia, physical or sexual abuse of children in the North, structural violence against children in the form of government policies, or symbolic forms of violence, looking at how images and representations of violence in the media affect children. It is difficult to cover all these topics in one course and the focus is necessarily limited. The course concentrates on three different environments where children experience violence: at home, among peers at school and in the wider society (in the context of armed conflicts). There is obviously an overlap between these environments and they are not meant to be mutually exclusive. It is an unfortunate fact that children may experience violence in their families and among their peers, and may also become involved in armed conflict.

This course focuses on children's experiences locally and globally, and emphasizes that violence against children should not be exoticized; it is not something that occurs only in other countries or in other families. Many children experience violence, whether they live in a Sierra Leonean war zone or experience bullying at school or domestic violence in the UK. Although the forms of violence that children experience may be different, the important point is that many children, throughout the world, have daily experiences of violence which can have negative impacts on their physical or emotional health. This course therefore moves from ideas about children and violence in very localized contexts – within families and with peers at school – through to the broader community and on to the international perspective. It also analyses the different roles that children take on in relation to violence, such as victim, perpetrator, witness, colluder and peacemaker.

In Western thought, children and violence exist in an ambivalent, and much debated, relationship with each other which centres around whether children are naturally good, gentle, kind and loving or naturally wicked and cruel (see Woodhead and Montgomery, 2003, Chapter 2). While the image of the gentle, meek child is integral to the Christian New Testament, many other Christian teachings, especially those in the Old Testament book of Proverbs and in the practices of some seventeenth-century Puritan sects, point to the inherent badness of children that must be controlled by punishment. Others have seen in children a particular form of violence, typified by cruelty to animals and to smaller children, which is linked to the innate savagery of children and their existence in a pre-civilized state. Nineteenth-century naturalists and archaeologists pointed to children as the closest available ‘savages’ who, like the ‘exotic primitives’ of Australia and North America, existed in a wilful, amoral and cruel state. C. Staniland Wake, an anthropologist writing in 1878, drew close parallels between children and ‘native peoples’, claiming that both were characterized by an innate viciousness towards others that glorified in violence for violence's sake. He wrote of a ‘cruelty so noticeable among children, so much so indeed, that it may be described as one of the most distinguishing traits of boyhood’ (Wake, 1878, p. 5). While the racism inherent in such statements may sound shocking nowadays, especially when written in such an objective, scientific tone, the casual assumption that violence and children are connected continues. The view that children, and especially boys, are cruel to animals, pulling the legs off spiders or tormenting cats, is commonplace.

However, the idea that children are cruel and violent is countered by the view that children are in fact naturally good and that any cruelty is a result of adult corruption. Ideas of children's innocence, gentleness and kindness can be traced back to the Romantic period in European history, characterized by philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and poets such as William Wordsworth. For the Romantics, children had a visionary quality and represented humanity in its uncorrupted state. They were born good and lacking in all violence and it was civilization that imposed violence on them.

Activity 1 Representations of children and violence

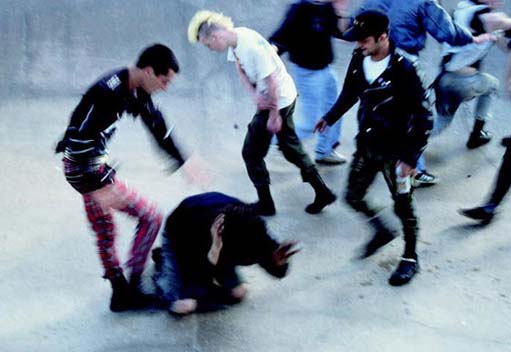

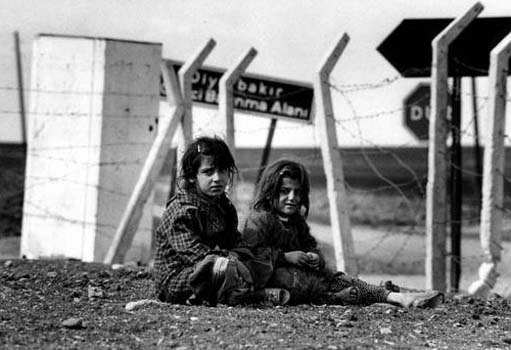

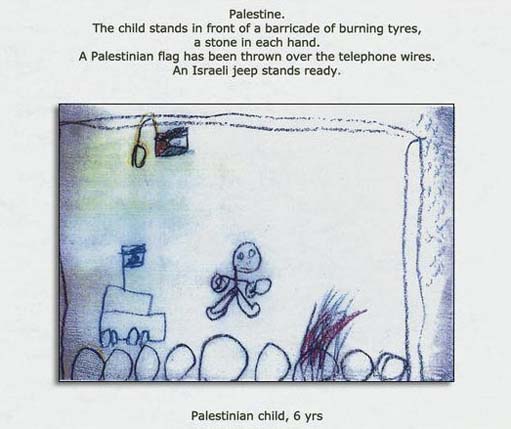

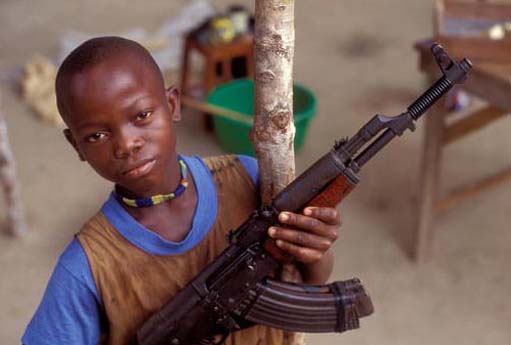

Study the pictures below. How do you react to them? In which do you see the child as innocent and in which do you see them as violent? Why do you feel this?

Discussion

These four pictures convey very different images of children and violence. It is hard to look at them without assigning innocence to some and violent intentions to others. The first image seems to show two girls play-fighting. They are smiling and apparently playing rather than hitting each other in anger. They are more likely to be seen as playing rough-and-tumble or romping than as committing violence. The second picture shows a child who is the victim of violence rather than a perpetrator. It is significant that both pictures show girls, in that, because of their gender, they are more likely to be seen as nonviolent. In Western societies, girls are invariably seen as less aggressive, less violent, more caring and more likely to be the victims of violence than its perpetrators (and this is largely backed up through crime statistics that suggest that girls are less likely than boys to commit violent crimes). In the final two pictures, however, vulnerability and innocence have gone and been replaced with images of children as threatening and dangerous. The fact that they are male might encourage the conclusion that they are violent. Their age is also significant. Teenagers are more likely to be seen as violent, and to pose a greater threat than younger children.

Summary of Section 1

Children and violence exist in an ambivalent relationship to each other.

In Western thought, children can be perceived as inherently violent and naturally cruel. Conversely, they are also seen as inherently gentle and lacking in violence.

Boys are more likely to be seen as violent and aggressive than girls, and teenagers as more violent than younger children.

2 Violence in the home

2.1 Violence towards children

For many children, the place where they experience most violence is in the home. Since the American paediatrician Henry Kempe first publicized the ‘battered child syndrome’ in 1962, the extent and nature of child abuse in the home has increasingly been recognized, and become the subject of research, legislation and social care practice. Following on from Kempe's claims that some children were routinely beaten and ill treated within their own families, other issues such as sexual abuse and emotional abuse have also come to the fore. The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) released a statement in 2002 which said:

Home Office figures show that the rate of child homicide in England and Wales has not dropped over the last 25 years. In each generation of children, more than a thousand will be killed before reaching adulthood. Most will die at the hands of violent or neglectful parents and carers.

(NSPCC, 2002)

The home is still the environment where children are most at risk, despite the widespread fears over ‘stranger danger’. In the UK, in 2001, 65 children under seven were killed by their parents or carers (NSPCC, 2002). Even if children themselves are not the direct victims of violence at home, they can witness domestic violence carried out by one parent on another.

Activity 2 Different forms of violence

Read through the list below. Which of these behaviours do you consider to show violence towards children? Why do you consider some of these to be forms of violence, and some not?

Being hit with a cane

Being shouted at

Overhearing parents arguing

Being told that you are stupid or ugly

Being smacked

Witnessing one parent hit another

Being tied into a cot or high chair

Being told ‘I hate you’ by a parent

Being humiliated in front of friends

Discussion

All the above might be considered different forms of violence against children. Although only hitting with a cane or being smacked involve the imposition of physical violence and pain, it is possible to argue that the others show some form of violence towards children. Humiliating a child or telling them ‘I hate you’ can be seen as a type of psychological violence that damages the well-being of a child. Whether or not these behaviours are seen as violence towards children further depends on cultural attitudes. For example, parents in Vietnam expressed shock and outrage to one researcher over ‘tying’ a child into a pushchair (Burr, 2000), a behaviour seen as so unremarkable in the UK as to be not worthy of comment. Indeed, the issue of restraint is a striking one because it may be seen as protecting children and ensuring their safety in the UK, yet considered inappropriate in Vietnam.

It may also depend on personal interpretation and your own experiences of being either a child or a parent. Furthermore, the intention needs to be taken into account. Many people argue that smacking is an acceptable form of discipline, seeing it as an effective form of training for good behaviour. Those who are opposed to smacking view it as a form of violence and unacceptable.

What constitutes violence towards children must therefore be seen in its cultural context – it must be acknowledged that practices and attitudes will differ markedly even within quite similar cultural contexts. There are some practices that are universally regarded as abusive and constituting violence towards children, such as sustained beating or shaking. However, there are other practices that are more contested. A clear example here is smacking, which remains widely practised in the UK, yet is looked upon with horror in Scandinavia where it is considered violent and abusive. In these countries, it is seen as an abuse of adult power against people who are smaller, weaker and more vulnerable. Similarly, what is considered violence towards children changes over time. In the 1970s in the UK, corporal punishment was widespread in British schools and viewed as a useful disciplinary tool for teachers. Now it is banned and if it occurred would be classified as assault.

While all societies have ideas about what constitutes unacceptable violence towards children, definitions of abuse vary across societies. For example, in certain Inuit societies of Canada, children are ‘toughened up’ from an early age by being made to plunge their hands repeatedly into icy water. Among some groups in Amazonia, boys are encouraged to show the bravery they will need to hunt later on by putting their hands in a wasp's nest and getting stung hundreds of times. From a Western perspective, these practices might seem cruel, or even violent, but amongst the people who practise them they are regarded as a necessary way of disciplining children and teaching them the skills they need to know later. Jill Korbin writes:

The parent who ‘protects’ his or her child from a painful, but culturally required, initiation rite would be denying the child a place as an adult in that culture. That parent, in the eyes of his cultural peers, would be abusive or neglectful for compromising the development of his child.

It is equally sobering to look at Western child-rearing techniques and practices through the eyes of these same non-Western cultures. Non-Western people often conclude that anthropologists, missionaries, or other Euro-Americans with whom they come into contact do not love their children or simply do not know how to care for them properly. Practices such as isolating infants and small children in rooms or beds of their own at night, making them wait for readily available food until a schedule dictates that they can satisfy their hunger, or allowing them to cry without immediately attending to their needs or desires would be at odds with the child-rearing philosophies of most … cultures.

(Korbin, 1981, p. 4)

In short, particular ways of treating children may be seen as violent in one cultural context, but as necessary restraint or even positive training in others. It is important to take account of these different cultural beliefs about violence, especially when making judgements about what counts as abusive. So far we have concentrated on violence towards children in the home. Next we turn to violent behaviour in children themselves. Of course, in practice the two are often connected, especially where a young child's misbehaviour provokes a violent reaction from a parent, initiating an escalating cycle of aggression (Patterson, de Baryshe and Ramsay, 1989).

2.2 Children's violence

There has been a great deal of work done by psychologists on violence and aggression in children, looking at whether this is part of a normal and natural developmental process or whether it is pathological. Cole and Cole define aggression as ‘an act in which someone intentionally hurts another’ (1996, p. 406). They then split this definition to look at instrumental aggression which is committed in order to obtain a specific goal, and hostile aggression which is aimed at hurting another person or showing dominance. They emphasize that intention is important and that discussions of children and violence should distinguish aggression from rough play. One of the earliest studies on this issue was carried out by Nicholas Blurton Jones (1972). He looked at the characteristics of aggression and rough-and-tumble play in an attempt to draw a distinction between violent and non-violent behaviour in children. Based on detailed studies of facial and bodily movements, he claimed that aggression is composed of ‘frown, fixate, hit, push, and take-tug-grab; whereas rough-and-tumble is characterized by laugh-playface, run, jump, hit-at and wrestle’ (quoted in Schaffer, 1996, p. 278).

He also claimed that these behaviours occurred in different contexts. For example, aggression is much more likely to occur when children are competing to play with the same toy, while play-fighting involves cooperating in a shared game. Children taking part in rough-and-tumble tend to play with smiles on their faces and to come back for more, whereas when children perceive aggression they are more likely to stay away from the other child. Blurton Jones also found that children who indulge in rough-and-tumble are no more likely to be violent in other contexts than those who do not.

In situations where children are in conflict, they express aggression in different ways according to their age and gender. Girls are less likely to use physical violence than boys and rely on emotional or psychological violence. Also, children's expressions of aggression become increasingly verbal as they get older. While two year olds will use what physical force they can, by the age of ten children are more likely to tease or humiliate other children. As Durkin suggests, children may have more scope to become aggressive as they get older.

Older individuals have more mechanisms available for acting aggressively. Not only do they have bigger, stronger, and better coordinated bodies, and in some cases access to more dangerous weapons, but they have also increasing competence in nonphysical means of aggression, such as verbal and nonverbal communications, and more sophisticated social understanding (so that, for example, they have a better sense of what will hurt someone else's feelings).

(Durkin, 1995, pp. 397–8)

While this course mainly concentrates on children's differing experiences of violence throughout the world, it is worth briefly noting some of the different hypotheses about why children are violent. Some psychologists and anthropologists have used theories from socio-biology to explain children's violence. These claim that violence is instinctive in humans and part of mankind's adaptive strategies for survival. Furthermore, they claim, boys are more likely to be violent than girls because of the effects of testosterone – their aggression is biologically determined. However, this is problematic, partly because research is inconclusive about the effects of testosterone (Durkin, 1995). Also, not all boys are violent or even aggressive and, in a society where aggression is downplayed, there is little evidence for these ideas. Girls are usually socialized to be less aggressive than boys and physical aggression in girls is viewed differently, and more negatively, than in boys. It is therefore difficult to know if girls are naturally less aggressive than boys or conditioned to be so. Indeed, such ideas do not take cultural conditioning into account and, as this section will go on to show, there are large variations cross-culturally in incidence and type of aggressive behaviour in children.

Other theorists claim that aggression and violence are learned rather than being innate. For example, Albert Bandura put forward a ‘social-learning theory’ of aggression (1977). This, he claimed, showed that children learned to be violent through observation. He pointed to the social factors in their lives and argued against looking at individual predispositions to violence. Bandura considered that violent behaviour is socially transmitted through parents, community and the media. When children see someone they admire or respect being aggressive and getting the results they want, they copy this and become violent themselves.

Most studies on children's violence have been based on children in North America or Europe. The work of anthropologists offers a broader perspective, demonstrating the power of cultural expectations in shaping children's behaviour, and in determining whether children's actions are considered violent. The following quote is from Napoleon Chagnon's Yanamamo: the fierce people (1968), concerning a group of Amerindians in Venezuela whose society is associated with the raiding of neighbouring communities, the killing of rivals, a high level of intra-group violence and physical violence inflicted by men on women.

Despite the fact that children of both sexes spend much of their time with their mothers, the boys alone are treated with considerable indulgence by their fathers from an early age. Thus, the distinction between male and female status develops early in the socialization process, and the boys are quick to learn their favored position with respect to girls. They are encouraged to be ‘fierce’ and are rarely punished by their parents for inflicting blows on them or on the hapless girls in the village. Kaobawä [his father], for example, lets Ariwari beat him on the face and head to express his anger and temper, laughing and commenting on his ferocity. Although Ariwari is only about four years old, he has already learned that the appropriate response to a flash of anger is to strike someone with his hand or with an object, and it is not uncommon for him to give his father a healthy smack in the face whenever something displeases him. He is frequently goaded into hitting his father by teasing, being rewarded by gleeful cheers of assent from his mother and from the other adults in the household.

(Chagnon, 1968, p. 84)

Amongst the Yanamamo, violence is classified as fierceness and is prized and appreciated. Children are therefore encouraged to show violent behaviour, in a way that would be unacceptable in other societies. However, this violence is also highly gender specific; fierceness in girls is not acceptable among the Yanamamo, even in self-defence, and is dealt with severely.

In other societies, a child who lashed out and regularly hit his parents or other children may well be seen as being disturbed or as showing inappropriate levels of violence and aggression. Even within a society, the norms of acceptable behaviour are different for boys and girls, and for younger and older children. Furthermore, different sections of the community, as well as individuals, have differing standards as to what they consider to be violent behaviour. These are also setting-specific, with different behaviours considered to be acceptable or non-acceptable, depending on whether they are occurring in the home, the classroom, the playground or on the football pitch.

Summary of Section 2

Violence against children can take the form of emotional, psychological, sexual or physical abuse.

Children's violence has to be contextualized by reference to the norms of a particular society, while recognizing that, even within a society, these norms may be contested.

Different levels of aggression are often deemed acceptable, according to gender, age and the site of the violence.

3 Violence between peers

3.1 Bullying – children as victims

In countries of the North, much of children's daily life is divided between home and school. It is therefore in schools that many children experience violence between their peers, from either being bullied or themselves bullying.

Click here to view Reading A

Reading

In Reading A (above), Dan Olweus, a psychologist specializing in children and bullying, looks at typical bullies and their victims in Sweden, although what he writes of Sweden is equally applicable to non-Scandinavian countries and North America. Read the extract, looking in particular at the links between home life and school behaviour, and noting the particular characteristics of those who are bullied and those who bully.

Discussion

This extract indicates that there is no clear division between violence between peers at school and violence at home. Olweus makes the point that ‘Violence begets violence’ – children who are exposed to violence at home are more likely to be violent at school. They are also likely to have had insufficient warmth and love from their parents. Later on in the article, Olweus claims that bullies are more likely than others to commit acts of violence later in life. He therefore sees a continuum between aggression at home, bullying at school and later criminality. However, this ‘cycle of abuse’ theory can be contested. Not all commentators agree that children who experience violence go on to commit it. Indeed, their experiences of violence may make them more empathetic and less likely to inflict violence on others. It would also be interesting to speculate on how far these findings could apply to the Yanamamo in Venezuela. Clearly, by Olweus's criteria, Yanamamo male children are very likely to grow up to be bullies but, in a society which encourages fierceness, this may well be seen as positive.

Much of Reading A is about what Olweus calls the typical characteristics of victims and bullies. It is important not to exaggerate these characteristics, implying that some children will inevitably either be bullied or become bullies. This runs the risk of overlooking the fluidity of roles that children take – they can be both victim and bully, depending on the circumstances. There is also a danger of overlooking the other roles that children may play in bullying, such as those of witnesses, peacemakers or colluders (those children who do not actively take part in bullying but encourage it to occur).

Activity 3 The effects of bullying

After reading Olweus's article, think about the effects of bullying. Make two lists – one of the possible physical effects and one of the psychological effects. In his article, Olweus concentrates largely on boys, but think back to the previous section where the differences between girls' and boys' experiences and ways of showing aggression were mentioned. Do you think that there would be any differences between the effects on boys and girls? To what extent do you regard bullying as a form of violence against children?

Discussion

When children are bullied, they may experience physical violence in the form of being hit or threatened. On the psychological level, they can be ostracized from their group, teased, humiliated, belittled or simply ignored, and can suffer loss of self-esteem and confidence. You may have written down other forms of violence present in school bullying.

In general, both boys and girls are subject to all these forms of bullying. However, there are some gender differences. Boys are more likely to commit physical acts of bullying while girls resort to emotional bullying. Girls are at less risk of direct attack from other children but are more subject to indirect attacks in the form of exclusion or ostracism from the group.

Bullying can have very damaging consequences for children. The quotes below are taken from a problem page of the charity Bullying Online. In them, children express their fears of bullying and clearly do see it as a form of emotional, as well as physical, violence.

Dear Liz

I'm 14 in March and I'm being bullied constantly. In nearly every class I sit by myself because nobody wants to sit next to me. One of my few friends hangs around with other people because I think he is frightened if he is with me he will get bullied. Please help me. I'm sick to death and sometimes I feel like killing myself. I wish I was dead. I have been to the doctor.

Mike

Dear Liz,

I go to a village school where there aren't many other children. Some of them are being very spiteful and not letting me play with them. They call me names and hit me when they think the teacher isn't looking. I'm aged 10 and my mum has been trying to get it stopped.

Lucy

(Bullying Online, 2002)

For some children, going to school can be a violent and alienating experience. One survey carried out anonymously in Sheffield, UK, found that 27 per cent of the 6,758 junior and middle school children surveyed were bullied ‘sometimes’ or more often and 10 per cent faced bullying once a week or more (Smith et al., 1999, p. 121). It is further claimed that sixteen children commit suicide in the UK each year as a result of bullying (Marr and Field, 2001). Yet it is only fairly recently that bullying has been recognized as a serious problem and seen as a form of violence against children. There has been a tendency among adults to see it as playing or teasing which occasionally gets out of hand or to see it as an inevitable fact of playground life out of which children will eventually grow (Smith et al., 1999).

Bullying in schools is not only a problem for the North. Although there is little research on the subject, studies from Ethiopia suggest that it is also a serious problem in the South. A study of one classroom in Addis Ababa reported:

Bullying and snatching objects (books, bags, etc.) are the most frequently occurring forms of violence, followed by physical violence (hitting, kicking, etc.). Attempts of rape at school are frequent among students, particularly among high school students (20 per cent of the total violence counted) …

A study in eight schools around Addis Ababa revealed that … [n]early 90 per cent of students reported that they have either repeated classes or dropped out of school due to violence.

(Ohsako, 1999, pp. 363–4)

Within schools, violence may also come from teachers, who bully or humiliate children or use physical punishment. This is especially common where teachers' methods of discipline are subject to few regulations. Many children find school a hostile and violent environment with its rigid hierarchies and punitive sanctions for breaking rules.

The following quotations come from a study of children in countries of the South, many of whom try to combine working with going to school.

[Teachers] pinch us … throw erasers at us … pull our hair … hit us with big sticks … make us kneel, hands raised and put books on our hands. (Philippines)

They beat us with a cane or a bamboo stick on our palms or back … At times they also push our head under a table and hit us on the buttocks. (Bangladesh)

When my parents did not buy exercise books, the teacher beat me. (Ethiopia)

(Woodhead, 1999, p. 42)

3.2 Children as perpetrators

There has been a great deal of research on the personalities of bullies (for an overview, see Smith et al., 1999) and explanations given for their behaviour in terms of family background or attachment to parents. Some of the findings of this research are summarized in Reading A. In another article, Olweus (1993) suggests that bullies are more likely to hold favourable views of violence, have a marked tendency towards aggression towards both adults and other children, have a strong need to dominate and feel more powerful than other children and feel little empathy for those they are bullying. But, as stated earlier, it is important to bear in mind that children can be both bullies and bullied in different contexts. There is also some evidence that children who are bullied may resort to violence themselves as a form of self-defence. Here, a boy in Australia recounts becoming a bully:

Harry: I used to fight all the time in year seven.

Martin: Why was that?

Harry: People didn't like me and they'd try to hit me and I'd react.

Martin: And when did things start to change?

Harry: When I fought back.

Martin: Do you think if you hadn't fought back that would have been a big problem?

Harry: Yeah it would have been.

(Mills, 2001, p. 69)

In other contexts also, children may turn to violence as a form of defence, aiming to be more violent than those of whom they are afraid. For example, street children in Brazil face an often brutal life where they are threatened and susceptible to violence from the police and the wider community, including older street children. Some children therefore turn to violence as a way of protecting themselves, using violence as both self-defence and a way of survival. Here, a child from Recife, Brazil, discusses his use of violence.

Once when I earned money, I bought a Beretta. I spent ten days snatching watches, ‘Pah, pah’ [his onomatopoeic rendition of children stealing watches]. First I bought a Mauser and then I held it against a lady's neck. I swiped her money and a bunch of videocassettes. I spent more than a month with the gun, stealing. Then I sold it and with the money I'd stolen and the money from the gun I bought a thirty-eight. Then I stole some more, sold that gun, and bought the Beretta.

I went to the street and a kid saw that my pockets were bulging, he tried to take my money. I pulled out the gun and pointed it at him. He took my money [anyway]. I said, ‘Give it back you asshole or I'll shoot you. You think I steal so you can come and take my money?’ He gave me the money and I yelled, ‘Run!’ He ran and I went ‘Bam!’ but I missed. ‘Take another!’ I missed again. When I shot again he fell. I said, ‘Shit, I killed a boy.’ I took off. The next day the kid had a Band-Aid on his toe. I only shot him in the toe.

(Hecht, 1998, p. 34)

3.3 Children as peacemakers – peer mediation

One response to witnessing bullying is to stand by and watch it happen. Alternatively, and more positively, children themselves can often act as mediators or peacemakers. Some of the most successful anti-bullying schemes have been those set up or run by children and have involved confronting the bully about the impact of his or her behaviour on others. Other schemes have involved setting up school bullying courts where children are ‘tried’ by a jury of their peers, while in others children counsel victims of bullying. In the following example, pupils at a school in Scotland talk about the anti-bullying programme that they have taken part in, emphasizing their role as peer mediators and counsellors.

You help them [children who are bullied] with a procedure of acknowledging the fact that they're being bullied and the fact that there is somebody who is there to listen to them and who can help them do something about it, and give them different options on different routes that they can take. And they have to choose which is basically what we do here. We don't force them to do things, we simply tell them what can be done and then they decide on the best way of handling their business.

In most cases I did, I found that … there's never a bully who does anything by themselves, there's always a friend who is, the friends are more threatening than actually the bully. And if you actually collar them by themselves, the bully, they eventually become very, very vulnerable and it's, that's when, that's how we basically approach them. You do not approach them with their friends, you approach them by themselves …

There is an advantage of us, the students dealing with the bullying rather than the teachers because students are more likely to open and feel comfortable with other students … Because if there was a scheme where it was just teachers doing it, I assure you, no student would be up there, because why would you want to go up to a teacher and start talking to them unless you are comfortable with them. Because teachers know they have authority over you but other students are on the same level as you and you are more likely to open up to them than you are to a teacher.

(Glenn, quoted on BBC Online, 2002)

The children in this project have tackled the issue of bullying head on and feel that they have made a significant difference to their school and community.

Summary of Section 3

Children take on different but sometimes overlapping roles in bullying, those of victim, perpetrator, colluder, witness and peacemaker.

Bullying can affect children's well-being and is a form of physical and psychological violence.

Children who bully often hold favourable views of violence, show aggression towards both adults and children, have a strong need to dominate and feel more powerful than other children and feel little empathy for those they are bullying.

Bullying is not confined to countries of the North.

Children can act as peer mediators, tackling bullying and holding the perpetrators to account.

4 Violence within armed conflicts

4.1 The effects of armed conflict on children

The final area of violence examined in this course involves children caught up in armed conflict, as victims, perpetrators or witnesses in violence affecting whole communities. It is important to emphasize that the three sites of conflict discussed in this course – family, schools and the community – are in no way exclusive. It is also important to stress that, in some parts of the world, criminal violence and repressive law enforcement measures (including harsh prison regimes) affect children's daily experiences of violence. Furthermore, gun violence against children is not limited to armed conflict. In some cities in the USA, children are as likely to be affected by violent death from guns as children living in a war zone. Psychologist James Garbarino refers to these as ‘war-zone neighbourhoods’, where

almost every fourteen-year-old has been to the funeral of a playmate who was killed, where two-thirds of the kids have witnessed a shooting, and where young children play a game they call ‘funeral’ with the toy blocks in their preschool classroom.

(Garbarino, 1999, pp. 17–18)

This section, however, will concentrate on the effects of armed conflict on children. These go far beyond injury and death to children and cause suffering to many children who are not directly involved. For example, during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, researchers found that children living in Kuwait suffered from anxiety and sleeplessness, loss of appetite, unexplained crying, bed wetting and unexplained physical symptoms such as headaches and stomach problems, even when they had not directly witnessed acts of violence. There were also rises in social problems such as truancy, poor academic performance and verbal and physical conflicts with teachers and other adults (King, 1999). At the end of the Gulf War, concern shifted away from Kuwaiti and on to Iraqi children, both those in the Kurdish and Shia communities of Iraq, who opposed Saddam Hussein and suffered persecution from state sources, and those who suffered as a result of the lack of food and medical care in the country, caused by the embargo on Iraq. These children too may be seen as casualties of war.

4.2 Violence within communities

Click here to view Reading B

Reading

The long-standing conflict in Northern Ireland had many repercussions for children. The effects of the terrorist and counter-terrorist activities have been extensively studied by Ed Cairns, who, in Reading B (above), looks at how violence affected children during the 1970s and 1980s. This reading was published in 1987, and consequently provides an account of Northern Ireland at a particular time in history. Although the situation is different today, the reading gives a good sense of how children experience the everyday effects of living in a civil conflict. It also emphasizes that, even in a modern, wealthy society such as the UK, war affects children's lives. As you read through it, note the various forms of violence that children suffer, both physical and emotional.

Discussion

In this extract, Cairns looks at both the physical and the psychological effects of war on children. The majority of children in Northern Ireland may not have been subjected to actual physical assault or have witnessed it directly, but Cairns points to the stress and difficulties many children faced under these circumstances. Many families were forced to move when they experienced violence because of their religion or their organizational affiliation. War, even a ‘low level’ conflict such as Northern Ireland, disrupts the daily patterns of people's lives, making children's families and homes part of the conflict.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1999 was supposed to bring a formal end to much of the terrorist violence in Northern Ireland. However, several people have been killed since and sectarianism remains entrenched. Other social problems have also become more visible in Northern Ireland since 1999. Crime has risen, drugs have become more widely available and young people have continued to be caught up in violence. Older youths are subject to arbitrary justice from paramilitary squads who threaten and carry out beatings or knee-cappings as punishment for a range of antisocial offences such as joyriding and taking or supplying drugs. Many of the victims of these are young men under eighteen. In 1999–2000, 47 youths under eighteen were punished by Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups, compared with 25 in 1997–98 (BBC Online, 2001). These groups claim to keep law and order in their respective communities, believing that these young people deserve their punishment and that, through such acts, order is kept. In other instances, being from the wrong part of the community in the wrong place is enough to be beaten up. Neville, aged seventeen, expresses this feeling of insecurity well.

They just want to know if you're a Protestant or a Catholic. And if you're in the wrong area, like, that's you hammered. You might as well book your hospital place now.

(Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Once again, in a situation such as Northern Ireland, children cannot be labelled simply as the victims of violence. Some children have also been perpetrators, throwing stones at soldiers or calling abuse. Some were simply passive witnesses to violence, while others were more active colluders. Some have been very politicized, seeing the conflict as a struggle of ideologies, others were socialized into violence by their families or their communities at a very young age. As Ciaran, aged seventeen, told researchers about his own induction into violence.

Time I was sent out, by the father, out to the police, wi' bottle – to throw at them. I was only five or six. I knew, well I knew it was wrong but I thought it was right because that's what I was taught to do.

(Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Activity 4 Children's induction into violence

Read the quotation below and make notes on the questions that follow it.

In Palestine rioting and stone throwing brought the local children to the attention of the world's media. However, far from being a childish behaviour … stone throwing amongst children in Palestine has been elevated to a military art with specific roles assigned to children of different ages. Those aged 7–10 years are given the job of rolling tyres into the middle of the road. These tyres are then set alight in order to disrupt traffic and attract Israeli soldiers. The next youngest age group (11–14 years) use slingshots to attack passing cars. These two groups are used to prepare the ground for … the ‘veteran stone throwers’. These young people use large rocks and inflict the worst damage on passing traffic and hence ‘they are the most sought after by the Israelis’. This command structure is coordinated by older youths who from the vantage points they occupy determine which cars to attack for example, or when to retreat when the soldiers advance.

(Cairns, 1996, pp. 112–13)

Do you see throwing stones at soldiers as ‘childish’ behaviour or is it an example of political violence among children?

Are these Palestinian children victims of violence or perpetrators of it? Should this affect the ways the Israelis treat them?

Discussion

These children have been raised in an atmosphere of violence and, to them, the Israelis are the enemy. They have suffered both direct violence in the form of family members killed or arrested and indirect violence in the form of prolonged curfews. Given this, it seems naive to dismiss their stone throwing as childish behaviour. The Israeli government, like the UK government, has found it very difficult to know how to react to young boys throwing stones at its soldiers. It is hard to know how politically aware and astute these children are, and therefore how knowingly violent, or whether they have been persuaded to take part by peer pressure or the chance to join in a group activity. It depends largely on your perception of children. If you believe that children are innocent, both of bad intent and of ideological motivation, then stone throwing is simply game playing. If, however, you believe that it is possible for children to be politically motivated and committed to a cause, then young people throwing stones are taking part in political violence.

There may also be another explanation for throwing stones at soldiers. In the absence of anything else to do, it may occur due to boredom. The children in Gaza and the West Bank have to cope with long curfews, while children in Northern Ireland also express a sense of frustration about their situation and their inability to change it.

Like something when we throw [things] cos you've nothing to do – the streets are boring … most of the tax money goes on helicopters and paying police. The money could be going on parks and theatres and football grounds and all that there. [I prefer] police out, parks, and all that stuff in.

(Luke, fourteen, quoted in Thomson, 2002, p. 16)

Children who are pictured throwing stones or rioting raise further questions about manipulation, not only by adults within their communities but also by the national and international media. Children may be encouraged to act up for the cameras or their political ideals may not be discussed, leaving their actions uncontexualized. The political beliefs of those who view the images will also alter how these children are seen – whether as nascent terrorists, freedom fighters or vulnerable children playing at war.

4.3 Children and the armed forces

The dual role of children as both perpetrators and victims of violence becomes very clear when looking at child soldiers. Despite international treaties, thousands of children worldwide fight in armies and paramilitary forces. Article 38 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states that no child under the age of fifteen should fight; supplementary international treaties, such as the 1999 Maputo Declaration on Child Soldiers and the 2000 Optional Protocol to the UNCRC on children in armed conflict, state that children under eighteen should not be involved as combatants in armed conflict. However, in 1999 Amnesty International claimed that there were at least 300,000 children under eighteen actively involved in armed conflict in countries as diverse as Sierra Leone, Liberia, Congo, Sudan, Uganda, Sri Lanka and Burma (Amnesty International, 1999). The increase in smaller, lighter weapons has made it easier for children to go into combat and fight alongside adults. Many others are not actual combatants but are used to plant or clear mines, as reconnaissance, as bearers and suppliers to the front line or as general ancillary workers, cooking, cleaning, keeping guard or delivering food.

4.3.1 Child soldiers in Sierra Leone, Burma and Uganda

Concern about child soldiers grew in the 1990s, with the conflict in Sierra Leone in particular providing many iconic images of a child soldier. The image of a child soldier is a difficult one. To see a young child with a machine gun or a rocket launcher is to look at a deeply incongruous and ambiguous image of childhood. Is this child a victim or a perpetrator of violence? Usually the story told of these children is that they were taken unwillingly by an army or quasi-military group and subjected to indoctrination and intimidation, sometimes given drink and drugs and sent out to kill. Two children from Burma and Uganda recount how they became soldiers.

Zaw Tun, aged fifteen, was forcibly conscripted for the Burmese army

I was recruited by force, against my will. One evening while we were watching a video show in my village three army sergeants came. They checked whether we had identification cards and asked if we wanted to join the army. We explained that we were under age and hadn't got identification cards. But one of my friends said he wanted to join. I said no and came back home that evening but an army recruitment unit arrived next morning at my village and demanded two new recruits. Those who could not pay 3,000 kyats had to join the army, they said. I could not pay, so altogether 19 of us were recruited in that way and sent to Mingladon [an army training centre].

(BBC World Service Online, 2002)

Susan, aged sixteen, abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda

One boy tried to escape [from the rebels], but he was caught … His hands were tied, and then they made us, the other new captives, kill him with a stick. I felt sick. I knew this boy from before. We were from the same village. I refused to kill him and they told me they would shoot me. They pointed a gun at me, so I had to do it. The boy was asking me, ‘Why are you doing this?’ I said I had no choice. After we killed him, they made us smear his blood on our arms … They said we had to do this so we would not fear death and so we would not try to escape … I still dream about the boy from my village who I killed. I see him in my dreams, and he is talking to me and saying I killed him for nothing, and I am crying.

(Human Rights Watch, 2001)

Not surprisingly, these children tend to downplay their actual involvement in violence. Their recruitment, they claim, was involuntary and when they took part in atrocities they did so out of fear and coercion. In many cases, no doubt, this is . However, it is also important to note that some children have been willing volunteers, finding in these armies a sense of purpose and comradeship and learning skills of loyalty, teamwork and independence.

The wars in Sierra Leone and Uganda in the 1990s were particularly brutal and it is not surprising that children have been caught up in atrocities. Even so, child soldiers have often provoked particular fear as being exceptionally brutal and without pity or mercy. Children who are recruited into paramilitary or state armies are often brutalized by having seen family members killed. Sometimes they have known nothing other than war and violence. They are seen as easy to manipulate and many have learned to distrust adult authority.

There is therefore another side to child soldiers and while they, and their supporters, claim that they are among war's victims, others have claimed that they are the perpetrators of violence and must be called to account for their actions. Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, has asked the United Nations Security Council to approve the prosecution of those child soldiers in Sierra Leone over the age of fifteen who were involved in murder, mutilation and rape (McGreal, 2000).

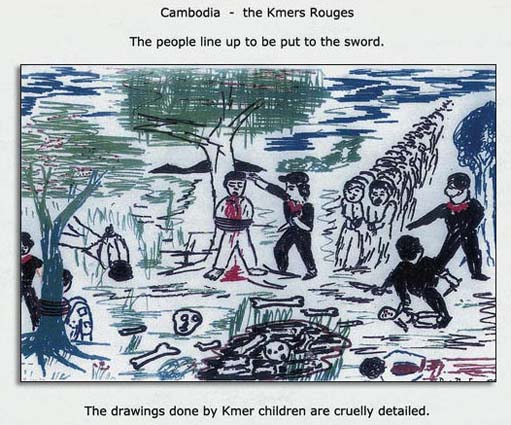

4.3.2 Children in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge

In 1975, Pol Pot's army, the Khmer Rouge, took over Cambodia and attempted to enforce an extreme Maoist communist regime, replacing all that went before. They restarted the calendar, renaming 1975 Year Zero. Their regime was murderous and, over the next four years, over 1 million Cambodians were killed and up to another 2 million died from starvation or exhaustion. The Khmer Rouge emptied the cities of people, forcing everyone to live off the land. Professionals, those who knew a foreign language and, at one time, even those who wore glasses were murdered. Much of this was accomplished by indoctrinating children and forcing them to denounce and kill suspect adults. Family life was discouraged and repressed. Everyone was forced to live in communal work camps, but at the age of eight most children were sent away to live with other children under two or three senior Khmer Rouge officials. Traditional norms of respect for elders were suppressed and the ‘Comrade Child’ was praised as being ‘pure and unsullied by the corrupt past of the adults’ (Ponchaud, 1977, p. 143). Special spy units, Kang Chhlop, were composed mainly of children and were used to spy on adults. One Cambodian woman recalled the power given to children under the Khmer Rouge:

In the Pol Pot times children could catch an adult if they thought they had done wrong. They could beat the adult. For example, if an adult was caught stealing fruit a child could tell the soldiers: ‘look they are our enemies’. Then the soldiers would set a chair for the child to stand on so that they could beat the adult's head.

(Boyden and Gibbs, 1997, p. 44)

Children rose quickly up the ranks of the Khmer Rouge and it was not unusual for children to be in charge of workcamps at the age of twelve. Camps run by these children became notorious for the extreme and arbitrary violence inflicted on the inmates. Children, even more than adults, appeared particularly cruel. Even after Cambodia was liberated in 1979 by the Vietnamese, there remained a ‘residual fear of children’ in the country (Boyden and Gibbs, 1997, p. 98).

4.4 Why shouldn't children fight?

Click here to view Reading C

Reading

There are many reasons why, ideally, children should not be allowed to join armies, but there are also reasons why children might want to fight and to protect themselves and their families. In Reading C (above), John Ryle puts forward a controversial argument about letting children fight and the reasons why, in some instances, they should. His argument is countered by Amnesty International's Martin Macpherson. Which viewpoint do you most agree with? Why?

Discussion

John Ryle argues that if children are in peril, then they have a right to self-defence and to protect their families. To keep them out of the army may compromise other rights, such as the right to have an opinion, to bodily integrity, to protection of life and property. He is particularly concerned to draw a distinction between voluntary and forced recruitment, claiming that this is more of a problem than age. In contrast, Martin Macpherson argues that children should never fight and sees the distinction between voluntary enrolment and force as untenable. He defines a child as any person under eighteen and feels that this line can, and must, be drawn to protect children from armed conflict.

Part of the idea of childhood innocence is the notion that children should be free from ideological motivation or political involvement. Yet, as John Ryle argues, there may be circumstances in which children should fight for a cause in which they believe. An important case here is that of the role of youth movements against the apartheid regime in South Africa. Children took an active part in the struggle, raising questions about whether, in the face of an illegal and brutal regime, it is morally right for children to fight. Often children were specifically targeted by the police and subjected to arbitrary whippings, detentions, tear-gassing or shootings. Between 1984 and 1986, 300 children were killed by the police, 1,000 wounded, 11,000 detained without trial, 18,000 arrested on charges related to protesting and 173,000 held in police cells (Cairns, 1996, p. 113). Given these statistics, it can be argued that South African children had no choice but to fight back. They were being directly targeted and their actions were in self-defence. Since the end of apartheid, the Truth and Reconciliation Committee has been set up to examine the injustices of the apartheid era. However, rather than celebrating children's resistance and their important role in the struggle, it has reduced many children to the role of victim, looking at crimes against them but not always recognizing their organization, their political commitment or their bravery.

Although the majority of child soldiers are in countries of the South, historically child soldiers and sailors have played an important part in European military history. One of the first acts of the Duke of Wellington when leading troops during the Napoleonic Wars was to put a stop to boys under eighteen (often in fact aged between ten and twelve) buying commissions in the army and leading troops into battle. More recently, in Europe during the First World War, children as young as fifteen signed up to fight and, even when they were obviously under age, the authorities turned a blind eye to their recruitment. Similarly, towards the end of the Second World War, Nazi Germany conscripted fifteen-year-olds into the army to make up for the numbers lost on the Russian front. There is also a long tradition in the UK of sending children to sea as a form of education and apprenticeship, from all classes – even royal children, such as Edward VII, who was sent to sea at fourteen in 1855.

Activity 5 Child soldiers in Britain

In the UK, in 2001, there were 6,000 soldiers under the age of eighteen serving in the armed forces. In March 2002, under pressure from the European Union, the government stated that these soldiers would no longer be sent into combat positions. However, Article 38 of the UNCRC states that fifteen is the minimum age for recruitment and there is no law which forbids children under eighteen to fight. What do you think are the arguments for and against keeping soldiers under eighteen out of armed combat?

Discussion

Until March 2002, the British government argued that, as there was no conscription, serving in the military was voluntary and therefore it was allowing young people the choice to serve their country if they so wished. Critics of this policy pointed to the discrepancy between children being allowed to fight in the UK army at sixteen, while still being considered children under international law. Furthermore, during the Gulf War, five British child soldiers were killed in action, which many saw as unacceptable. Barry Donnan, a young man who signed up to join the British Army at sixteen and saw combat in the Gulf War at seventeen, clearly sees this policy as potentially damaging to young people.

Perhaps if I'd been a bit older then, you know I'd probably have had a better chance of getting back to a bit of normality afterwards. And I think, being so young, with so many multiple incidents, effectively, you know you're at a point where … your nature's changing, your character's changing, and I think probably that will just stay with me for the rest of my life … I would say being young … made its differences.

(The Open University, 2003)

The accounts of child soldiers in Asia, Africa and Europe all draw attention to the ambiguous status of young people who take up arms. These ambiguities also surface when deciding how they should be treated. This is the topic of the next section, which looks at strategies for re-integrating child soldiers, especially in Africa.

4.5 Strategies for reintegrating child soldiers

Activity 6 Rehabilitating child soldiers

Child soldiers in several African countries have been guilty of committing atrocities against civilians. To what extent do you feel that child soldiers ought to be held accountable for their crimes?

Discussion

For many, the rehabilitation of child soldiers is very problematic. The term ‘rehabilitation’ is itself contested, as it implies that responsibility is removed from the society that generated the violence in the first place and that it is the individual children who are at fault and need to be resocialized. Others have argued that, whatever they have done, they are still children and cannot be held responsible for actions that they did not necessarily understand. However, many of those who have suffered because of the violence of child soldiers believe that they should be tried and punished. There is a great reluctance to see them as anything other than the perpetrators of particularly gruesome acts. As one child soldier told a researcher:

I am eleven years old now. Five years of my life was characterized by cutting limbs, killing, raping and drug abuse. Here I am. I cannot trace my relatives. I beg for food in the streets of Freetown. Even if I find my relatives, who will want to take a child like me? … My innocence was exploited, my development was violently suppressed, my identity contaminated almost irreparably; my parents and anything that gave me a sense of safety was annihilated.

(International Bureau for Children's Rights, 2000)

The issue of rehabilitating child soldiers is a very fraught one. Successful rehabilitation depends strongly on the circumstances of the war and the actions of the children.

Communities that have been caught up in war view children's involvement in violence in ways that are contingent on the nature, length and ferocity of the conflict; the choice or lack of choice the young had in participating; the actions they carried out; and the consequences for members of the family. Clearly attitudes to the young who fight against oppression and for liberation differ profoundly from attitudes to the young who kill and maim as members of warring groups.

(Reynolds, 2001)

However, there is a recognition that these children must be returned to their communities in order to break the cycle of violence. For example, encouraged by local mosques and churches, some adults in Sierra Leone have become foster parents to former child soldiers, attempting to teach them about family life and to trust adults again. Nevertheless, in some cases in Sierra Leone and Uganda communities have not felt able to have child soldiers back among them until they have been disarmed and debriefed by an outside agency. In this instance, healing cannot take place only in the community and a third party is involved. To this end, some agencies have set up camps where children are counselled and reintegration is attempted. This may involve children confronting their victims and being forced to account for themselves and ask for forgiveness. But many of these children also need to come to terms with what happened to them and to forgive those who forced them into becoming child soldiers. In one such centre in Uganda, thirteen-year-old Charles Oranga describes meeting the man who kidnapped him and forced him into becoming a soldier:

I felt like killing my kidnapper when I first met him … But then I was told that he had only done it because he was forced to – and I later did the same thing as well.

That made me see the other side: it is not hard to forgive someone when they tell you that. We ended up playing football together. He's not a friend, but I have no hatred anymore.

(Wazir, 1999, p. 1)

At the time of writing, in Uganda and Sierra Leone, such projects are having some success, but the number of children involved is still small. The scale of the problem is also overwhelming. Not only do these children have emotional scars but they often have physical ones too. One project in Sierra Leone removes the tattoos and scars that children were marked with (or in some instances inflicted on themselves) which branded them as members of a particular militia. By getting rid of these markers, it is hoped that children will not be permanently reminded by their bodies of the atrocities that they witnessed and committed.

There is, however, no one acknowledged model of how to treat child soldiers or indeed any children so dramatically affected by violence, especially those caught up in brutal conflicts in Africa and Asia. While Western experts tend to look to therapy and counselling, some commentators have begun to question whether this is an appropriate response. Indeed, many now prefer to emphasize models of healing and forgiveness rather than counselling or psychological help (see Reynolds, 2001). Community mediation has had some successes and some non-governmental organizations support it as a way of ending the violence that dominates those countries. The role of children themselves in this is also crucial. They must be seen not as passive victims who need to be ‘rehabilitated’ but as active agents who can rebuild their communities and act as peacemakers in the reintegration process.

However, this is far from straightforward. When resources are scarce, as they usually are in war-torn countries, rehabilitation of child soldiers is often a low priority. When communities have been destroyed, it is impossible to reintegrate a child into a community that no longer exists. Furthermore, many wars in which children are involved do not have a clear ending, so that anxiety remains entrenched. Community mediations and child peacemakers are therefore no panacea. They must be seen as one more strategy alongside rebuilding communities and countries destroyed by war, supporting people's attempts to work and to gain education for their children. Helping child soldiers should be seen in the context of the resources that a country has and the way it chooses to spend them.

Summary of Section 4

War affects many aspects of society and therefore all children in societies at war are affected by violence, even if they do not experience violence directly.

Children are involved in armed conflict in many countries, not only in the South. In Northern Ireland, children have suffered as a consequence of the military and paramilitary presence.

Children can be targeted directly by military and paramilitary groups and be either forced to become involved or punished for not doing so.

Some child soldiers join for ideological reasons or to protect their homes and families.

It is very difficult to reintegrate children into their communities if they are perceived to have been responsible for violence against it. Western-style counselling has proved inappropriate in many instances. Community reintegration programmes, where the emphasis has been placed on healing and forgiveness, have had greater success in some African countries.

5 Conclusion

This course has concentrated on three main environments for violence and the roles that children play within these environments: victim, perpetrator, witness, colluder and peacemaker. It has looked at individual and social experiences of violence, examining what is normal and abnormal child behaviour and whether violence is innate or learned. It has also broadened out these discussions to look at the ways child violence is differently understood in a range of cultural contexts. What is clear from this examination is that children at both a local and a global level experience multiple and complex forms of violence which shape their experiences of childhood, and which constitute, for many, an extreme form of adversity.

This course and the previous two have looked at three different forms of adversity as they affect children. Clearly there is an overlap between them: children suffer health consequences as a result of war and they may become impoverished if they are forced to flee their homes as a result of armed conflict. Similarly, poverty can lead to civil unrest and uprising which in turn place children at risk from armed conflict.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Course image: Maximilian Imran Faleel in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Reading A: Olweus, D. (1999) ‘Sweden’, The Nature of School Bullying, Smith, P. K. et al. (eds), Routledge, Taylor and Francis Books Ltd;

Reading B: Cairns, E. (1987) Caught in Crossfire: children and the Northern Ireland conflict, Appletree Press Ltd;

Reading C: Ryle, J. (1999) ‘Children at arms’, The Guardian, 25 January 1999. Copyright © John Ryle;

Reading C Postscript: Macpherson, M. (1999) ‘Letter to the editors of the New York Review’, New York Review of Books, 4 March 1999, reproduced by permission of Martin Macpherson.

Figure 1 Christa Stadtler/Photofusion;

Figure 2 Colin Edwards/Photofusion;

Figure 3 S. Scott-Hunter/Photofusion;

Figure 4 Giacomo Pirozzi/Panos Pictures;

Figure 5 Bryan and Cherry Alexander Photography;

Figure 5 Richard House/Hutchison Picture Library;

Figure 6 John Maier/Still Pictures;

Figure 7 Roy Peters/Report Digital;

Figure 8 Howard Davies/Exile Images;

Figure 9 Associated Press, AP;

Figure 10 Scott Nelson/Getty Images;

Figure 11 Dr Alfred Brauner;

Figure 12 Giacomo Pirozzie/Panos Pictures;

Figure 13 Dr Alfred Brauner;

Figure 14 Jim Holmes/Panos Pictures.

Giacomo Pirozzie/Panos Pictures;

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University