Project governance and Project Management Office (PMO)

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 2:04 PM

Project governance and Project Management Office (PMO)

Introduction

This free course, Project governance and Project Management Office (PMO), introduces you to the important Project Management topic of project governance and how a Project Management Office can support governance. Project governance may be highly formalised, within the organisational governance, for large projects, or programmes or portfolios of projects. In smaller organisations, perhaps with less complex projects, some of the governance and support for the project may be undertaken by the project manager themselves. Whatever the context, the roles and responsibilities for project governance need to be clear and appropriate for the project and the organisation.

This OpenLearn course is an extract from the Open University course M815 Project Management. You may also be interested in the OpenLearn course Managing virtual project teams, which looks particularly at leadership and communication in project team which are not collocated.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the principles of effective governance of projects

be aware of the roles and responsibilities of those involved in project governance such as project board, project sponsor, project manager and Project Management Office

recognise the different types of Project Management Office and the services they provide

identify good governance or make recommendations to improve governance by using project experience

understand the importance of good communication between all stakeholders in project governance.

1 Governance

The governance of a project is much like the governance of an organisation.

Project governance is:

The set of policies, regulations, functions, processes, and procedures and responsibilities that define the establishment, management and control of projects, programmes or portfolios.

Some projects are run solely by the project manager. Where this is appropriate for the type of project, and the organisation, it is not necessary to have all the aspects of governance that are discussed in this section.

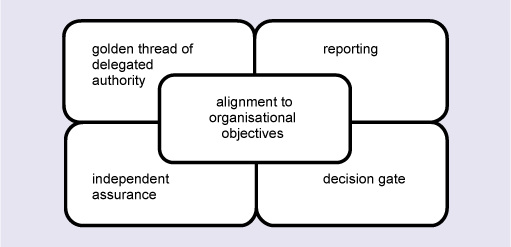

Figure 1 illustrates good governance as explained by Murray (2011). Murray’s explanation is compatible with the APM definition but focuses just on projects rather than including programmes or portfolios too. He gives five elements, based on project governance or project management governance, with emphasis on alignment to organisational objectives as a central aspect of good governance. He uses the term ‘decision gate’ in place of a stage gate or approval gate.

The diagram illustrates the five elements of project governance as explained by Murray (2011). The diagram shows four rounded rectangles arranged to form the four quarters of a larger rectangle. Each rectangle is labelled with one of the elements of project governance. Starting with the top left rectangle, the rectangles are labelled, clockwise, as follows:

- Golden thread of delegated authority

- Reporting

- Decision gate

- Independent assurance

The fifth element of project governance is shown in a rounded rectangle in the centre of the larger rectangle, superimposed over the four quarters of the larger rectangle. The central rectangle is labelled:

- Alignment to organisational objectives

- Alignment to organisational objectives means that the projects undertaken by an organisation should be able to demonstrate, in the business case, the contribution to the organisation’s objectives. With this contribution clearly stated then the project context is clear and governance of the project can ensure that the project is focused on the outcome rather than activities.

- The golden thread of delegated authority is a direct chain of accountability. Within this chain each person needs to know what their authority is and what needs to be referred to a higher level of authority within the chain.

- Reporting – those to whom responsibilities have been delegated should periodically report on progress. In addition to period reporting, additional reports need to be made if the person with delegated responsibility is unable to fulfil that responsibility, or if conflicts of interest arise.

- Independent assurance is a counterbalance to self-reporting, and is an independent check of the structures and processes to review whether the objectives will be met.

- Decision gates – at specified points in the project life cycle − provide formal points of control where a decision is made to grant or renew authority for the project to continue.

The strategic management of an organisation identifies and implements the long-term goals of that organisation. The choice of projects (in programmes or portfolios if appropriate), and carrying them out successfully, is part of the organisation’s activities to achieve those goals. Therefore the organisation, at the strategic level, typically needs to establish the governance structures for the management of projects. Organisations have corporate governance, of which project governance is a subset. Project management incorporates those aspects of project governance that are at the project level, as well as managing the detail of the project.

The APM identifies the following ways in which good governance can be demonstrated:

- The adoption of a disciplined life cycle governance that includes approval gates at which viability is reviewed and approved.

- Recording and communicating decisions made at approval gates.

- The acceptance of responsibility by the organisation’s management board for project governance.

- Establishing clearly defined roles, responsibilities and performance criteria for governance.

- Developing coherent and supportive relationships between business strategy and projects.

- Procedures that allow a management board to call for an independent scrutiny of projects.

- Fostering a culture of improvement and frank disclosure of project information.

- Giving members of delegated bodies the capability and resources to make appropriate decisions.

- Ensuring that business cases are supported by information that allows reliable decision making.

- Ensuring that stakeholders are engaged at a level that reflects their importance to the organisation and in a way that fosters trust.

- The deployment of suitably qualified and experienced people.

- Ensuring that project management adds value.

You will see from this list that demonstrating good governance is about clarity of roles and responsibilities, about processes, and about the relationships between people and within an organisation. The list is applicable for any context and any size of project, and other factors may be important for specific projects and specific contexts. A key factor is the role of the host organisation and the senior management. This applies whether the project reports directly to the board or through a management structure for programmes and/or portfolios of which the project might be a part. Organisations that are less oriented to projects may leave more of the project governance to the project team, which is acceptable provided this is agreed by the project sponsor. The project sponsor also needs to ensure that the agreed governance processes are being followed and this scrutiny should be carried out by someone external to the project team. This scrutiny is known as ‘project assurance’ and is likely to be part of the host organisation’s corporate quality assurance.

The APM also emphasises the importance of the relationship between the project sponsor and the project manager (APM, 2012a). Good inter-personal skills are needed, together with clarity about responsibilities. The project sponsor is accountable for the achievement of the project objectives as specified in the business case, and providing senior management level support for the project. The project manager is responsible for the daily management of the project. The appropriate choice of a project management approach or method can support the governance of projects by defining the structure for the management of the project, including options for customising or adapting the approach or method for the particular project.

1.1 The project board

The project board, also known as the project steering committee, is responsible for ensuring that the project is properly managed. The project board may be for that specific project, or a board may look after a group of projects in the organisation. Such a group of projects might be a programme or a group of individual projects. For a smaller project, the sponsor may undertake all the responsibilities for that project. For a larger project, the responsibilities may rest with a project board of which the project sponsor may be the chair. In an organisation without the infrastructure to support projects, the governance may be undertaken by the project manager who would then be directly responsible to the organisational management. However, in a large, project-oriented organisation, the project board sits between any projects and the organisational senior management.

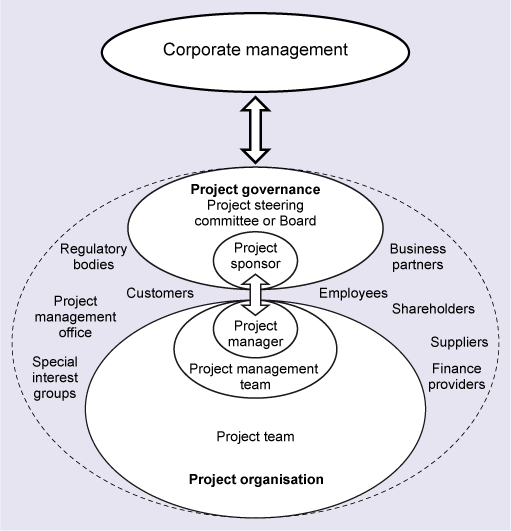

The diagram shows the relationships between stakeholders in a project, from ISO21500. Three ellipses are positioned vertically above each other. The smallest diameter of each ellipse is from top to bottom through the centre of the shape.

The three ellipses are labelled, in order:

- Corporate management

- Project Governance

- Project Organisation

The largest ellipse at the bottom of the diagram represents ‘Project Organisation’ and the ‘Project team’ are shown within this space. Within this large ellipse there is a smaller ellipse and the ‘Project management team’ is shown within this space. Within this ellipse there is another smaller ellipse and the ‘Project Manager’ is shown within this space. These three ellipses which describe the stakeholders in the ‘Project Organisation’ are joined at the upper point of each ellipse.

The ellipse in the middle of the diagram representing ‘Project Governance’ shows ‘Project Steering Committee or Board’ within this space. Within this ellipse there is a smaller ellipse and the ‘Project Sponsor’ is shown within this space. These two ellipses which describe the stakeholders in ‘Project governance’ are joined at the lower point of each ellipse.

A double-headed broad arrow links the ellipses showing ‘Project Sponsor’ and ‘Project Manager’.

An ellipse formed by a dashed line surrounds the ellipses for ‘Project Governance’ and ‘Project Organisation’. The ellipse formed by a dashed line is joined to the top of the ellipse for ‘Project Governance’ and is joined to the bottom of the ellipse for ‘Project Organisation’. Within the space formed by this ellipse but external to the ellipses for ‘Project Governance’ and ‘Project Organisation’, other stakeholders are shown.

On the left the following stakeholders are shown:

- Regulatory Bodies

- Project Management Office

- Special Interest Groups

- Customers

On the right the following stakeholders are shown:

- Business Partners

- Shareholders

- Suppliers

- Finance providers

- Employees

The ellipse at the top of the diagram, which is roughly equal in size to the middle ellipse, is labelled ‘Corporate management’.

A double-headed broad arrow links the ellipse showing ‘Corporate management’ and the ellipse formed by a dashed line.

Figure 2 is adapted from the International Standard ISO 21500 Guidance on Project Management (ISO, 2012). Senior management can be grouped together, but in Figure 2 the Corporate management stakeholders, who are part of the project and organisational infrastructure, are shown separately outside the system boundary of the project, although it may be appropriate to represent them inside the boundary, depending on structures within a particular organisation. The project sponsor is part of the project board or project steering committee. Following the definition of roles within ISO 21500:

- The project sponsor authorises the project, makes executive decisions, and solves problems and conflicts beyond the authority of the project manager.

- The project board contributes to the project by providing senior level guidance to the project.

PRINCE2 published by The Office of Government Commerce (OGC, 2009a) expresses the project board differently, including an executive, senior users and senior suppliers. The suppliers may be external to the organisation, or may be internal managers of the resources needed for the project. Senior users would usually be the customer, or representing views of the customer, whether this is an internal customer or an external customer. This is an example of governance applied across organisational boundaries and it can facilitate formal mapping of roles such as technical specialists communicating directly with each from different areas. The common aspect of the project board from both the ISO standard and PRINCE2 is that the project manager is responsible to the board, but is not part of the board. The project board may establish a ‘project assurance team’ that represents the three interests and performs this role working separately from the project team.

The project sponsor is the individual who has responsibility for ensuring that:

- appropriate governance mechanisms are in place for the project

- project assurance processes take place through periodic monitoring of the governance mechanism.

The monitoring may be by the project sponsor themselves, or by someone to whom the authority has been delegated. If delegated, this should be to someone who is external to the project.

1.2 The project sponsor

We have explained the APM articulation of how good governance is demonstrated, however, it is less straight forward to explain how this is achieved, although clear roles and responsibilities have been highlighted. In Crawford et al. (2008) a survey across five continents with several projects or programmes based in each is described. This research is interesting because it builds on the recognition that the sponsor can be crucial to the success of a project, and it investigated the role of the sponsor and the connection between the sponsor and governance of projects. Crawford et al. make a distinction between two perspectives that may exist at the interface of the act of governing the project:

- governance, in the interests of the host organisation – governing the project that requires looking at the project from the perspective of the host organisation

- support, in the interest of the project – top management support that requires looking at the host organisation from the perspective of the project.

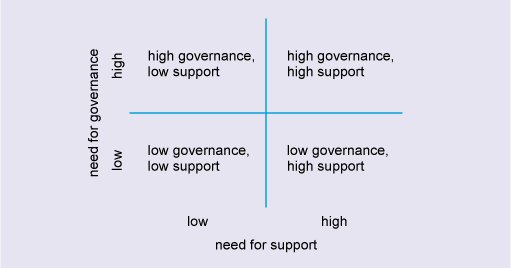

The sponsor both ensures that governance requirements are met and provides support to the project. Crawford et al. (2008) suggest the model shown in Figure 3 as a way of clarifying the role and responsibility of the project sponsor. They suggest that this clarification is needed because the sponsor’s role has informal aspects as well as formal responsibilities. The corporate and project governance define the formal aspects, and the model is intended to support the understanding of the balance of support and governance needed in the effective performance of the sponsor’s role. To identify which quadrant is applicable for a particular project the perspectives of the organisation and the project need to be considered.

Figure 3 shows a conceptual framework for examining the two perspectives in the context of the project sponsorship. The role of project sponsor is ongoing, and continued engagement with the project is likely to be essential. However, what that engagement needs to be will vary between projects, and is also likely to vary over the life cycle of a single project. The primary responsibility of the sponsor, to ensure that the project objectives are set within the business case, should not be lost in the other considerations addressed by this conceptual framework.

The diagram shows a framework for examining the need for governance and the need for support in the context of project sponsorship. The diagram shows four squares formed by a vertical line and a horizontal line, crossing at a mid-point. The ‘need for support’ is shown along the bottom of the diagram, with the two left-hand squares labelled ‘low’ need for support, and the two right-hand squares labelled ‘high’ need for support. The ‘need for governance’ is shown along the left-hand side of the diagram, with the two top squares labelled ‘high’ need for governance, and the two bottom squares labelled ‘low’ need for governance.

The four squares are labelled:

Top left: high governance, low support

Top right: high governance, high support

Bottom left: low governance, low support

Bottom right: low governance, high support

It is also possible for the project sponsor to change over the lifetime of a project. For longer projects this becomes more likely, and may arise from change of staff within the organisation, or even where the strategic priority attached to a project changes so that the sponsor also changes.

1.3 Communication of governance arrangements

Four principles of effective project governance are given in the book Project Governance: A Practical Guide to Effective Project Decision Making (Garland, 2009), but the communication of governance arrangements is not included. Nor is communication specifically identified in the APM list of how good governance is demonstrated. In the context of governance, the communication skills of the project sponsor and the project manager need to be very effective. Good communication can help to reduce conflict in many contexts, and clear governance policies enable communication of problems and concerns in a formal and constructive way. The route for escalation is made clear in the governance, so that problems can correctly be communicated upwards. To communicate upwards may mean through the project manager to the project sponsor or project board, or to external functions within the organisation.

Activity 1

How is project governance communicated and implemented in the projects you work on? Are there standards, methods or organisational requirements that are well known, with roles and responsibilities clearly defined, or is governance something that is ‘done by someone else’? Is the route for communicating upwards clear to you, whether within the project, or between the project manager and the project sponsor?

If your study has introduced you to new ideas about governance can you suggest principles that your organisation or your project need to consider to improve the governance of projects? Might you be able to discuss this with work colleagues?

Discussion

In this section of this course, communication of governance arrangements is last but this may be the section that is most relevant to this activity. How easily you were able to address the first part of the activity probably depends on how well governance arrangements are communicated, and you need to have been able to do this before you could consider the final question in the activity.

Communication is a topic that is important throughout project management.

2 The Project Management Office (PMO)

Good governance, as discussed earlier, requires clear roles and responsibilities and this may be achieved through a permanent structure within the host organisation. This structure then supports the temporary structure of each project that is undertaken. In an organisation that has portfolios and programmes, the permanent structure will usually support all the projects, programmes and portfolios. This section considers the support structure, i.e. the infrastructure, required where an organisation undertakes various projects and has a PMO.

The Association for Project Management (APM) states:

Infrastructure provides support for programmes, portfolios and projects, and is the focal point for the development and maintenance of P3 management within an organisation.

The definition of a PMO by the Project Management Institute (PMI) is more specific:

A Project Management Office (PMO) is a management structure that standardises the project-related governance processes and facilitates the sharing of resources, methodologies, tools, and techniques. The responsibilities of a PMO can range from providing project management support functions to actually being responsible for the direct management of one or more projects.

The role of the PMO is a difficult one to define accurately due to the variations in approach by organisations and individuals. This section gives generic classifications to define the main aspects of the role and to discuss the possible variations in structure, approaches and responsibilities. The terms Enterprise Project Management Office (EPMO), Project, Programme or Portfolio Support Office (PSO), Project Services or Centre of Excellence are all in common use (APM, 2012a). The Project Support Office (PSO) is sometimes focused on administrative functions and may be for a specific project, although some authors use PMO and PSO synonymously. A Centre of Excellence is organisation-wide and has a much broader remit as the name suggests.

In larger, more mature organisations, the PMO has grown as a separate body from the management of the project. It can be a career path in itself or it can be an opportunity for a project manager to bring their own experience into a PMO at the same time as refreshing their own skills.

2.1 To have a PMO or not

To have a PMO or not depends on the size and type of the projects, the available resource pool within the organisation and the skills of those resources. Routine administration is required on all projects, programmes and portfolios. On small projects this may be performed by the project manager, possibly supported by a deputy project manager, but on medium to large projects and all programmes and portfolios, a project manager (and the programme and portfolio manager) needs support in handling day-to-day administration. There may also be a need for specialist knowledge, for example, in risk, quality or finance. These skills may be beyond the skills of the project manager, especially early in their career, and may therefore need to be resourced from elsewhere, either inside or outside of the organisation.

Additional support for the project manager may be available from the operational functions of an organisation, for example in finance or procurement. Alternatively, a support office may be set up for the specific project and then disbanded when that project is completed. A permanent PMO is likely to be established when a role is recognised that exists beyond the lifetime of an individual project. An example of this would be where there are organisational requirements for standard documentation. This may be time consuming for a project manager, who might need to familiarise themselves with each type of documentation as the project progresses, whereas a PMO that handles the documentation for several or many projects would build experience in completing the documentation.

There is also a need for a PMO where there are programmes and portfolios of projects (so that the support for a project is provided by the programme or portfolio office) or where there is a group of independent projects that can benefit from sharing the expertise and resources of a PMO. This is common in large government contracts, such as the armed forces, or the larger government departments, such as the Department of Environment. The construction and utility supply (electricity, oil and gas) industries are two other examples of the type of project that requires dedicated support facilities with specialist skills, experience, expertise, tools and techniques to help in their management. Experience in a PMO can be accumulated in many aspects of project work within the organisation so the PMO may develop over time to become a Centre of Excellence.

A permanent PMO has a place within the development of project management skills for the organisation, not just for individual projects. As well as supporting organisational and project governance it may also act as the knowledge broker for learning from projects and coordinate training and staff development for projects.

Without a PMO, the project manager will need to ensure that the necessary support services are in place for the particular project. The project manager may take on these activities themselves or make sure team members are available. For a small standalone project, there may not be sufficient resource for a specific support function. The APM recommends that in this case the project manager should seek as much support as possible with the project administration, and that the project sponsor should support the project manager in this (APM, 2012a).

When a PMO or other support function is decided upon, its purpose, roles and responsibilities need to be clearly defined and be communicated effectively to the support function and the project, or projects, they are supporting. The scope needs to be clearly understood by all so that the relationship between the support function and the projects has the opportunity to be mutually beneficial. PMO relationships with the project manager, the project and the organisation are discussed later.

2.2 Types of PMO

There are different ways to classify a PMO. This section uses generic classifications depending on the level to which the PMO is responsible for the development of the project management function within the organisation.

Basic PMO or PSO

The basic PMO, which might be called a Project Support Office (PSO), provides basic administrative support to the project manager. It has no responsibility for development of the project management function. In the basic PMO or PSO the stress is on support and the responsibilities are of a lower order than for a PMO where the emphasis is on the management of the project. In the latter case the responsibilities are more stringent and managerial than pure support. It is important that the responsibilities of the PMO or PSO of any type are defined by the organisation and are clear and unambiguous.

A basic PMO typically exists for a specific project and is likely to undertake, for example:

- administration of the record keeping, such as filing and change management of project documents

- general communication with the project team

- less high profile, administrative tasks such as meeting and travel arrangements.

Intermediate PMO

The intermediate PMO has some responsibility for the development of the project management function within the organisation. It needs to maintain and promulgate the processes, procedures and other mechanisms to enable the operation of common standards of project management within all projects undertaken by the organisation. This includes use of standard tools, and possibly specialist tools, existing within the organisation to facilitate the monitoring, control and status reporting of projects: scheduling, financial, risk management, document management, status recording and governance, for example.

Advanced PMO

An advanced PMO may have wide-ranging responsibilities for the setting up and development of the project management function within the organisation. In this case the PMO will lead on the design, and develop, implement, operate, maintain and communicate the processes, procedures and other mechanisms needed to enable the operation of common standards of project management within all projects undertaken by the organisation. This includes the definition, selection, introduction, implementation and use of standards, tools, processes, procedures, modes of operation deemed necessary by and within the organisation to facilitate the monitoring, control, management and status reporting of the projects in question (e.g. scheduling, financial, risk management, document and configuration management, status recording and governance).

To enable an advanced PMO to carry out these tasks, the knowledge and skills of the PMO personnel need to be superior to those required for the basic and even intermediate PMO. The selection, education, training and continuous development of the PMO personnel required to carry out these tasks is also the responsibility of the PMO.

2.2.1 PMO within organisational culture

An alternative approach to classifying the type of PMO is to consider the degree of control and influence that the PMO has on the projects within the organisation. This is the approach recommended by the PMI:

Supportive. Supportive PMOs, or PSOs, provide a consultative role to projects by supplying templates, best practices, training, access to information and lessons learned from other projects. This type of PMO serves as a project repository. The degree of control provided by the PMO is low.

Controlling. Controlling PMOs provide support and require compliance through various means. Compliance may involve adopting project management frameworks or methodologies, using specific templates, forms and tools, or conformance to governance. The degree of control provided by the PMO is moderate.

Directive. Directive PMOs take control of the projects by directly managing the projects. The degree of control provided by the PMO is high.

2.3 PMO services

The services provided by a PMO depend strongly on the size, maturity and capability of the organisation. A smaller and/or less mature organisation may undertake fewer projects, and therefore the PMO in such an organisation will have less capability to provide a full range of services. The larger the organisation, the more projects they undertake and therefore there is a greater need for project support. Consequently the capability grows to provide more, and higher level, support.

The following descriptions are drawn primarily from the APM Body of Knowledge (APM, 2012a) and PMI Body of Knowledge (PMI, 2013). Which services are included in the responsibilities of the PMO for each type of activity will depend on the type of PMO and their role within the organisation and the function of the organisation.

Planning and scheduling

All types of PMO, whether basic, intermediate or advanced, will be involved with planning and scheduling. For a basic PMO this may be entering and updating information generated by the project manager, whereas an advanced PMO may take the lead in actively seeking information from different parts of the project team, drafting schedules and recommending resources drawing on experience from similar projects already undertaken within the organisation.

Administration

Again, all types of PMO will be involved in administration, but the degree of administration and the level of autonomy of the PMO will vary. A basic PMO will provide the necessary administrative support to the project manager but the authority will remain with the project manager. An advanced PMO may have a high level of influence or authority when interacting with the project manager. For example, an advanced PMO may collate the information and prepare documentation for the project board when assessing the continued financial viability of the project compared with the business case at gate reviews or stage reviews.

Reporting

Reporting is a key service provided by the PMO, however, the degree of reporting will depend on the type of PMO. A basic PMO typically reports only to the project manager, who then reports to the project sponsor and senior management. The way in which an intermediate or advanced PMO and the project manager interact to produce reports, for example, who takes the lead and who supports, will depend on the roles and responsibilities of both the project manager and the PMO within the organisation and the governance structure.

Specialist skills

In bid management the organisation’s business development department would take the dominant role, and the project sponsor is usually the lead for the business case. A basic PMO may undertake the purely administrative support, whereas an advanced PMO may be involved in the collating and reporting to senior management responsible for the prioritisation of projects and the allocation of resources. At this level the advanced PMO is supporting decision making at the executive level.

Professional development

This group of services is firmly in the realm of the advanced PMO and has a broader function in supporting the development of organisational maturity within the field of project management.

Financial control

‘The rise of the PMO’ contains an answer to the question: ‘What advice would you give to PMOs to develop their capability?’ It highlighted the important role that the PMO might play, or might aspire to, as the repository of knowledge and skills within an organisation.

2.4 PMO relationships

The PMI classification shows that PMOs can be powerful and, in some activities and situations, may have more control over a project than the project manager. Therefore, the roles and responsibilities between the project manager, the PMO and other parts of the organisation (such as project sponsor and senior management) need to be clearly defined and effectively communicated. The PMOSIG mentions ‘wariness of PMOs’ by the project management profession, rather than ‘curtail(ment) of autonomy’. It is more often concerned with increased bureaucracy and constrained decision making.

Demarcations between PMOs and project managers are an interesting question for stakeholder management and the balance of power between them. The need for clearly defined roles and responsibilities had already been mentioned. Earlier in this course we highlighted the need for good communication skills and these are equally needed in stakeholder management and in communicating and negotiating with senior managers.

The PMI (2013) refers to the PMO as the liaison between the corporate management systems and the project management (and portfolio and programme management), particularly in bringing together the data and information needed by organisational senior management. In undertaking this, and other support roles, the PMO brings together projects within the organisation that may not be related to each other in any way except being supported or administered by the PMO. It is therefore essential that the PMO functions and structures are defined by the needs of the organisation. This is especially important where the PMO itself is a stakeholder and decision maker.

As a decision maker a PMO is likely to be making recommendations about the continuation, or not, of projects to ensure that organisational activities, and the deployment of organisational resources, remain aligned with the business objectives. In this context, the PMO and the project manager are pursuing objectives that may not be the same; whereas the PMO is concentrating on the strategic organisational objectives, the project manager is focused on the objectives of the specific projects. For example, from PMI (2013) these differences might include:

- The project manager focuses on the specified project objectives, while the PMO manages major programme scope changes, which may be seen as potential opportunities to better achieve business objectives.

- The project manager controls the assigned project resources to best meet project objectives, while the PMO optimises the use of shared organisational resources across all projects.

- The project manager manages the constraints (scope, schedule, cost, quality, etc.) of the individual projects, while the PMO manages the methodologies, standards, overall risks/opportunities, metrics, and interdependencies among projects at the enterprise level.

This is not to suggest that the PMO and the project manager are frequently in conflict. The decision to go ahead with a specific project would have been part of the business strategy but there may be changes in the business environment that might give rise, from time to time, to differences. Communication between the PMO and the project manager is needed to discuss and resolve such differences.

There will be a relationship between the PMO and the organisational quality assurance team and when working well this will be symbiotic, so that experience of one supports the other and problems identified in one area, which might impact elsewhere, can be shared, explored and resolved. The PMO or other members of specific project teams may be represented on the quality assurance team. When an audit is due, the project manager typically prepares the project team. This preparation can build the team confidence in responding to the auditor. The PMO may support the project manager in audit preparation.

An advanced PMO will have organisational oversight for quality assurance within the governance structure. This will include spot checks and scheduled audits. Since audits are undertaken by someone outside of the project, a member of the PMO may be the auditor. Training PMO staff as auditors develops this expertise within the organisation and also can support sharing of good practice.

2.5 Designing a PMO

Organisations with a history of undertaking projects probably already have a PMO or an equivalent. This section initially takes the approach of designing a PMO, so we can think about what project managers and project teams want from the PMO. The PMO also has responsibilities to the organisation, which should not be dismissed.

The first question is whether a PMO is needed at all. A PMO is probably not needed if the organisation is small, deals mainly with smaller projects, and the departments in the organisation interface effectively with projects. In such a case it might increase the bureaucracy of projects without adding value.

Activity 2

You are an experienced project manager in a large and mature organisation. To encourage the sharing of good practice between the PMO and project managers, project managers work for a period of two to six months within the PMO at least once every three years. You are currently working within the PMO and have been invited to give a talk at the local university to project management students. The topic you have been invited to talk on is: ‘How to establish a PMO in an organisation’. What do you think you would say in your talk?

Discussion

Does your organisation need a PMO? When considering the support needed for projects within an organisation the following questions need to be asked:

- What is the size of the organisation − large, medium or small?

- What type of organisation is it? Does it only do one thing or many different things?

- What does the organisation do? In particular, what types of projects and of what scale?

- How are projects supported now? Is this from the rest of the organisation or is support embedded in the projects themselves? Or perhaps support is bought in from elsewhere (i.e. some service provision).

If the organisation is considering setting up a PMO then firstly you need to look at what is ‘the big picture’ for this organisation and its interest in PMO?

- Do you need a PMO?

- Why do you need a PMO?

- What sort of PMO do the project managers need?

- What does the PMO need to do to provide support to the organisation?

All these different attributes, conditions and criteria will determine the need for a PMO and the shape that the PMO needs to take. If your organisation already has a PMO then similar questions can be asked to review whether the PMO provides the support needed and identify any changes which might be required.

Whether setting up an new PMO or reviewing an existing PMO it will be important to look at two key aspects:

- Who does it need to employ within itself to provide the support that the organisation has identified is needed for its’ projects? What skills, expertise and experience do its people need and what is the extent of its remit?

- How is,or does, the PMO going to interact with project managers and with the rest of the organisation?

This is a high level approach. The stakeholders would all need to be consulted and an approach agreed by all major stakeholders. Without this commitment the introduction of a PMO, or changes to an existing PMO, might be resisted and the opportunities to add value would be reduced.

Advantages and disadvantages of a PMO within an organisation

Advantages have been explained so far and there is the potential for many:

- strong governance processes and support

- routine and specialist support for the project manager

- consistency of approach across an organisation, commonality of documentation

- focus of reference to standards, methods, tools, etc.

- development of skills and sharing of best practice.

Disadvantages might relate to:

- the PMO will not necessarily have the support services available to deal with potential difficulties of projects that do not fit the organisational pattern and require new skills and processes

- the specific needs of particular projects might be compromised by employing standard practices across an organisation, for example, it might be difficult to prioritise smaller projects.

Conclusion

This free course, Project governance and Project Management (PMO), has introduced you to the principles of effective project governance, and the roles and responsibilities of the project board, the project sponsor, the project manager and the Project Management Office. A PMO or Project Support Office may provide a range of services, and these need to be agreed and understood by all the project stakeholders. As for all governance within organisations, effective communication is very important and is a key skills for all project managers. The topics we have discussed, such as the different types of PMO and the types and variety of services that they may provide, will enable you to reflect on your own experience of project management administration and support, and identify possible improvements.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Kay S. Bromley.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course Image © Rawpixel/iStockphoto.com

Figure 1: adapted from Murray, A. (2011) White Paper: PRINCE2 and Governance, November 2011, London, The Stationary Office.

Figure 2: from: ISO (2012) ISO 21500 Guidance on Project Management, London, International Organization for Standardizationhttp://www.iso.org/ iso/ home/ standards.htm

Figure 3: Adapted from Crawford, L. et al. (2008) ‘Governance and support in the sponsoring of projects and programs’, Project Management Journal, Vol. 39, Issue no. S1, Supplement, pp. S43-S55, doi: 10.1002/pmj.20059.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

1. Join over 200,000 students, currently studying with The Open University – http://www.open.ac.uk/ choose/ ou/ open-content

2. Enjoyed this? Find out more about this topic or browse all our free course materials on OpenLearn – http://www.open.edu/ openlearn/

3. Outside the UK? We have students in over a hundred countries studying online qualifications – http://www.openuniversity.edu/ – including an MBA at our triple accredited Business School.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University