Week 2: Essential numerical skills for accounting

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 6:12 PM

Week 2: Essential numerical skills for accounting

Introduction

Expertise in mathematics is not required for you to succeed as an accountant. The core skill needed is the confidence and ability to be able to add, subtract, multiply, divide as well as use decimals, fractions and percentages. The learning material this week thus covers the basic numeracy skills from multiplication and division, through to decimals, percentages, fractions and negative numbers. It is expected that you will use a calculator for most of the activities but you are also encouraged to use mental calculations.

An important skill in accounting is also the ability to manipulate simple equations. This week you will also be introduced to the accounting equation which is the foundation of the double-entry system of accounting. Being able to understand and express the accounting equation in different forms is crucial to understanding and preparing the balance sheet (the principal financial statement) and the income statement.

2.1 Mastering accounting numeracy

Competent accountants should be able to use mental calculations as well as a calculator to perform a range of numerical tasks.

In the modern world, the assumption is that we use calculators to save the tedious process of working out calculations by hand or mentally. The danger, of course, is that you may use a calculator without understanding what an answer means or how it relates to the numbers operated upon. For example, if you calculate that 8% of £20 is £160 (which can easily happen if either you forget to press the percent key or it is not pressed hard enough), you should immediately notice that something is very wrong.

Using a calculator requires certain skills in understanding what functions the buttons perform and in which order to carry out the calculations. Your need to study this material is dependent on your mathematical background. If you feel weak or rusty in basic arithmetic or maths, you should find this material helpful. The directions and symbols used will be those found on most standard calculators. If you find any of the instructions contained in this material do not produce the expected answer, please look at the instructions for your calculator and amend the instructions in this week so that they match those for your own calculator.

There are four basic operations between numbers, each of which has its own notation:

Addition 7 + 34 = 41

Subtraction 34 – 7 = 27

Multiplication 21 x 3 = 63, or 21 * 3 = 63

Division 21 ÷ 3 = 7, or 21/3 = 7.

The next section will examine the application of these operations and the correct presentation of the results arising from them.

2.2 Use of BODMAS and brackets

When several operations are combined, the order in which they are performed is important. For example, 12 + 21 x 3 might be interpreted in two different ways:

(a) add 12 to 21 and then multiply the result by 3

(b) multiply 21 by 3 and then add the result to 12.

The first way gives a result of 99 and the second a result of 75. We need some way of ensuring that only one possible interpretation can be placed upon the formula presented. For this we use BODMAS, which give us the correct sequence of operations to follow so that we always get the right answer:

(B)rackets

(O)rder

(D)ivision

(M)ultiplication

(A)ddition

(S)ubtraction.

According to BODMAS, multiplication should always be done before addition, therefore 75 is actually the correct answer using BODMAS.

(‘Order’ may be an unfamiliar term to you in this context but it is merely an alternative for the more common term, ‘power’, which means a number is multiplied by itself one or more times. The ‘power’ of one means that a number is multiplied by itself once, i.e., 2 x 1, 3 x 1, etc., the ‘power’ of two means that a number is multiplied by itself twice, i.e., 2 x 2, 3 x 3, etc. In mathematics, however, instead of writing 3 x 3, we write 32 and express this as three to the ‘power’ or ‘order’ of 2.)

Brackets are the first term used in BODMAS and should always be used to avoid any possibility of ambiguity or misunderstanding. A better way of writing 12 + 21 x 3 is thus 12 + (21 x 3). This makes it clear which operation should be done first.

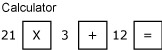

12 + (21 x 3) is thus done on the calculator by keying in 21 x 3 first in the sequence:

This calculation shows:

21 times key

3 plus key

12 equals key.

The next activity will test your ability to use brackets properly.

Activity 1 Use of BODMAS

Complete the following calculations.

- (13 x 3) + 17

Answer

56

- (15 / 5) - 2

Answer

1

- (12 x 3) / 2

Answer

18

- 17 – (3 x (2 + 3))

Answer

2 (Did you enter the expression in the inner brackets i.e. (2 + 3) first?)

- (13 + 2) / 3 - 4

Answer

1

- 13 x (3 + 17)

Answer

260

2.3 Use of calculator memory

A portable calculator is an extremely useful tool for a bookkeeper or an accountant. Although computers normally provide computer applications, there is no substitute for the convenience of a small, portable calculator or its equivalent in a mobile phone or tablet.

When using the calculator, it is safer to use the calculator memory (M+ on most calculators) whenever possible, especially if you need to do more than one calculation in brackets. The memory calculation will save the results of any bracket calculation and then allow that value to be recalled at the appropriate time. It is always good practice to clear the memory before starting any new calculations involving its use. (Consult your own calculator manual for its method of storing any calculation in memory as well as its instructions for clearing memory.)

Box 1 The memory function in a scientific calculator

The scientific calculator memory is particularly useful for more complex calculations in accounting. Such a calculator has a number of different memories of which the ‘M’ memory is the most commonly used in accounting calculations. Like most calculators, the ‘M’ memory is accessed using the M+ key. Only the most basic calculator is needed for this course but a scientific calculator should be strongly considered for any future study in accounting.

Activity 2 Use of calculator memory

Use the memory on your calculator to evaluate each of the following:

- 6 + (7 – 3)

Answer

10

- 14.7/(0.3 + 4.6)

Answer

3

- 7 + (2 x 6)

Answer

19

- 0.12 + (0.001 x 14.6)

Answer

0.1346

2.4 Rounding

For most business and commercial purposes the degree of precision necessary when calculating is quite limited. While engineering can require accuracy to thousandths of a centimetre, for most other purposes tenths will do. When dealing with cash, the minimum legal tender in the UK is one penny, or £00.01, so unless there is a very special reason for doing otherwise, it is sufficient to calculate pounds to the second decimal place only.

However, if we use the calculator to divide £10 by 3, we obtain £3.3333333. Because it is usually only the first two decimal places we are worried about, we forget the rest of them and write the result to the nearest penny of £3.33.

This is a typical example of rounding, where we only look at the parts of the calculation significant for the purposes in hand.

Consider the following examples of rounding to two decimal places:

1.344 rounds to 1.34

2.546 rounds to 2.55

3.208 rounds to 3.21

4.722 rounds to 4.72

5.5555 rounds to 5.56

6.9966 rounds to 7.00

7.7754 rounds to 7.78

Rule of rounding

If the digit to round is below a 5, round down. If the digit is 5 or above, round up.

Activity 3 Use of rounding

Part A

Round the following numbers to two decimal places:

- 0.5678

Answer

0.57

- 3.9953

Answer

4.00

- 107.356427

Answer

107.36

Part B

Round the same numbers as above to three decimal places:

- 0.5678

Answer

0.568

- 3.9953

Answer

3.995

- 107.356427

Answer

107.356

2.5 Fractions

So far we have thought of numbers in terms of their decimal form, e.g., 4.567, but this is not the only way of thinking of, or representing, numbers. A fraction represents a part of something. If you decide to share out something equally between two people, then each receives a half of the total and this is represented by the symbol ½.

A fraction is just the ratio of two numbers: 1/2, 3/5, 12/8, etc. We get the corresponding decimal form 0.5, 0.6, 1.5 respectively by performing division. The top half of a fraction is called the numerator and the bottom half the denominator, i.e., in 4/16, 4 is the numerator and 16 is the denominator. We divide the numerator (the top figure) by the denominator (the bottom figure) to get the decimal form. If, for instance, you use your calculator to divide 4 by 16 you will get 0.25.

A fraction can have many different representations. For example, 4/16, 2/8, and 1/4 all represent the same fraction: one quarter or 0.25. It is customary to write a fraction in the lowest possible terms. That is, to reduce the numerator and denominator as far as possible so that, for example, one quarter is shown as 1/4 rather than 2/8 or 4/16.

If we have a fraction such as 26/39 we need to recognise that the fraction can be reduced by dividing both the denominator and the numerator by the largest number that goes into both exactly. In 26/39 this number is 13 so (26/13)/(39/13) equates to 2/3.

We can perform the basic numerical operations on fractions directly. For example, if we wish to multiply 3/4 by 2/9 then what we are trying to do is to take 3/4 of 2/9, so we form the new fraction:

3/4 x 2/9 =(3x2)/(4x9) = 6/36 or 1/6 in its simplest form.

In general, we multiply two fractions by forming a new fraction where the new numerator is the result of multiplying together the two numerators, and the new denominator is the result of multiplying together the two denominators.

Addition of fractions is more complicated than multiplication. This can be seen if we try to calculate the sum of 3/5 and 2/7. The first step is to represent each fraction as the ratio of a pair of numbers with the same denominator. For this example, we multiply the top and bottom of 3/5 by 7, and the top and bottom of 2/7 by 5. The fractions now look like 21/35 and 10/35 and both have the same denominator, which is 35. In this new form we just add the two numerators.

(3/5) + (2/7) = (21/35) + (10/35)

= (21 + 10)/35)

= 31/35

Activity 4 Use of fractions

Part A

Convert the following fractions to decimal form (rounding to three decimal places) by dividing the numerator by the denominator on your calculator:

- 125/1000

Answer

0.125

- 8/24

Answer

0.333

- 32/36

Answer

0.889

Part B

Perform the following operations between the fractions below, giving your answers in fraction form:

- 1/2 x 2/3

Answer

1/3

- 11/34 x 17/19

Answer

187/646 = 11/38 (if top and bottom both divided by 17)

- 2/5 x 7/11

Answer

14/55

- 1/2 + 2/3

Answer

7/6 or 1 1/6 (intermediate step is 3/6 + 4/6)

- 3/4 x 4/5

Answer

12/20 simplified to 3/5 (12÷4 / 20÷4 = 3/5)

2.6 Ratios

Ratios give exactly the same information as fractions but expressed in a different form. Accountants make extensive use of ratios in assessing the financial performance of an organisation.

A supervisor’s time is spent in the ratio of 3:1 (spoken as ‘three to one’) between Departments A and B. (This may also be described as being ‘in the proportion of 3 to 1.’) Her time is therefore divided: 3 parts in Department A and 1 part in Department B.

There are 4 parts altogether and:

3/4 time is in Department A

1/4 time is in Department B

If her annual salary is £24,000 then this could be divided between the two departments as follows:

Department A 3/4 X £24,000 = £18,000

Department B 1/4 X £24,000 = £6,000

Activity 5 Use of ratios

A company has three departments that make use of the canteen. Running the canteen costs £135,000 per year and these costs need to be shared out among the three departments on the basis of the number of employees in each department.

| Dept | Number of employees |

| Production | 125 |

| Assembly | 50 |

| Distribution | 25 |

How much should each department be charged for using the canteen?

Answer

| Production | (125 / (125 + 50 +25)) x £135,000 | = £84,375 |

| Assembly | (50 / (125 + 50 +25)) x £135,000 | = £33,750 |

| Distribution | (25 / (125 + 50 +25)) x £135,000 | = £16,875 |

2.7 Percentages

Percentages also indicate proportions. They can be expressed either as fractions or as decimals:

45% = 45/100 = 0.45

7% = 7/100 = 0.07

Their unique feature is that they always relate to a denominator of 100. Percentage means simply ‘out of 100’, so 45% is ‘45 out of 100’, 7% is ‘7 out of 100’, etc.

A business is offered a loan to a maximum of 80% of the value of its premises. If the premises are valued at £120,000 then the company can borrow the following:

£120,000 x 80% = £120,000 x 0.80 = £96,000.

Fractions and decimals can also be converted to percentages.

Box 2 Changing decimals or fractions to percentages

To change a decimal to a percentage you need to multiply by 100:

0.8 = 80%

0.75 = 75%

To change a percentage to a decimal you need to divide by 100:

60% = 0.6

3% = 0.03

To convert a fraction to a percentage it is necessary to first change the fraction to a decimal:

4/5 = 0.8 = 80%

3/4 = 0.75= 75%

If a machine is sold for £120 plus VAT (Value Added Tax – an indirect tax in the UK) at 20% then the actual cost to the customer is:

£120 x (20% of 120) = £120 + (0.20 x 120) = £144

Alternatively, the amount can be calculated as

£120 + (100% + 20%) = £120 x (1.00 + 0.20) = £120 x 1.20 = £144

If the machine were quoted at the price including VAT (the gross price) and we wanted to calculate the price before VAT (the net price), then we would need to divide the amount by (100% + 20%) = 120% or 1.2. The gross price of £144 divided by 1.2 would thus give the net price of £120. This principle can be applied to any amount that has a percentage added to it.

For example, a restaurant bill is a total of £50.40 including a 12% service charge. The bill before the service charge was added would be:

£50.40 / 1.12 = £45.00

Activity 6 Use of percentages

- Convert the following to percentages:

- a.0.9

Answer

90%

- b.1.2

Answer

120%

- c.1/3

Answer

33.33%

- d.0.03

Answer

3%

- e.1/10

Answer

10%

- f.1 1/4

Answer

125% (i.e. 100 x 1.25)

- A company sells its product for £65 per unit. How much will it sell for if the customer negotiates a 20% discount?

Answer

£65 x (1 – 0.2) = £52

- If a second product is sold for £36.18 including 20% value added tax, what is the net price before tax?

Answer

£36.18 / 1.2 = £30.15

2.8 Negative numbers and the use of brackets

Numbers smaller than zero (shown to the left of zero on the number line below in Figure 2) are called negative numbers. We indicate they are negative by enclosing them in brackets as shown in Figure 2.

There are numbers in a horizontal line.

In the centre is a zero.

To the left of the zero are the numbers 1 to 7 each in brackets. These represent negative numbers.

To the right of the zero are the numbers 1 to 7 without brackets. These represent positive numbers.

You may be used to seeing negative numbers indicated by the use of a minus sign ‘–’. However, because accountants conventionally use brackets so as to make it more obvious that a value is negative; this is the convention we adopt in this OpenLearn course. Negative numbers can be manipulated just like positive numbers and the calculator can deal with them with no difficulty as long as they are entered with a ‘–’sign in front of them.

Box 3 Rules of negative numbers

The rules for using negative numbers can be summarised as follows:

Addition and subtraction

Adding a negative number is the same as subtracting a positive

50 + (-30) = 50 – 30 = 20

Subtracting a negative number is the same as adding a positive

50 – (-30) = 50 + 30 = 80

Multiplication and division

A positive number multiplied by a negative gives a negative

20 x -4 = -80

A positive number divided by a negative gives a negative

20 / -4 = -5

A negative number multiplied by a negative gives a positive

-20 x -4 = 80

A negative number divided by a negative gives a positive

-20 / -4 = 5

Try to confirm the above rules for yourself by carrying out the following activity either manually or by means of a calculator.

Activity 7 Use of negative numbers in maths operations

Calculate each of the following. (In this activity we will assume the convention that if a number is in brackets it means it is negative.)

- (2) x (3)

Answer

6

- 6 – (8)

Answer

14

- 6 + (8)

Answer

(2)

- 2 x (3)

Answer

(6)

- (8) / 4

Answer

(2)

- (8) / (4)

Answer

2

Box 4 An important note about the use of brackets

Always remember that while a single number in brackets means that it is negative, the rule of BODMAS means that brackets around an ‘operation’ between two numbers, positive or negative, means that this is the first operation that should be done. The answer for a series of operations in an example such as 12 + (- 8 – 2) would thus be 2 according to the rules of BODMAS and negative numbers. It should be also noted that if 12 + (- 8 – 2) was given as 12 + ( (8) – 2) the answer would still be 2 as (8) is just another way of showing -8.

2.9 The test of reasonableness

Applying a test of reasonableness to an answer means making sure the answer makes sense. This is especially important when using a calculator as it is surprisingly easy to press the wrong key.

An example of a test of reasonableness is if you use a calculator to add 36 to 44 and arrive at 110 as an answer. You should know immediately that there is a mistake somewhere as two numbers under 50 can never total more than 100.

When using a calculator it is always a good idea to perform a quick estimate of the answer you expect. One way of doing this is to round off numbers. For instance if you are adding 1,873 to 3,982 you could round these numbers to 2,000 and 4,000 so the answer you should expect from your calculator should be in the region of 6,000.

Test your ability to perform the test of reasonableness by completing the following short single-choice quiz. Do not calculate the answer, either mentally or by using an electronic calculator, but try to develop a rough estimate for what the answer should be. Then determine from the choices presented to you which makes the most sense, i.e., the choices that are most reasonable.

Activity 8 Use of test of reasonableness

a.

18

b.

180

c.

0.18

The correct answer is a.

a.

44.2

b.

442

c.

4,420

The correct answer is b.

a.

8.5

b.

85

c.

0.85

The correct answer is a.

a.

277.2

b.

2,772

c.

27,772

The correct answer is b.

a.

547

b.

647

c.

747

The correct answer is b.

a.

194

b.

294

c.

394

The correct answer is b.

2.10 Table of equivalencies

The next activity in developing your numerical skills required for accounting is to give you practice in converting between percentages, decimals and fractions. It is a very useful numerical skill to be able to know or to work out quickly the equivalent between a number given in percentage form and in other forms.

Activity 9 Use of equivalencies

Fill in the correct answers for the gaps in table below. The first one is done for you. Answers required in decimals should be rounded off to two decimal points. Answers required in fractions should be written in the lowest possible terms.

Table 3 Completion of missing equivalencies

Answer

| Percentage | Decimal | Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 0.01 | 1/100 |

| 2% | 0.02 | 1/50 |

| 5% | 0.05 | 1/20 |

| 10% | 0.1 | 1/10 |

| 20% | 0.2 | 1/5 |

| 25% | 0.25 | 1/4 |

| 33 ⅓ % | 0.33 | 1/3 |

| 50% | 0.5 | 1/2 |

| 66 2/3 % | 0.67 | 2/3 |

| 75% | 0.75 | 3/4 |

| 100% | 1.0 | 1/1 |

| 200% | 2.0 | 2/1 |

2.11 Manipulation of equations

An equation is a mathematical expression that shows the relationship between numbers through the use of the equal sign. An example of a simple equation might be 3 + 2 = 5.

An equation could also be in the form of £5,000 - £2,000 = £3,000 to express mathematically the accounting fact that sales of £5,000 minus costs of £2,000 equals a profit of £3,000. (An important aspect of mathematics, but not of accounting, is that £5,000 - £2,000 = £3,000 can be simplified as 5 – 2 = 3.) Another well-known use in accounting of an equation is the accounting equation, which you will learn in more detail next week. The accounting equation is the basis of the balance sheet, which you will learn how to produce in Week 4.

Box 5 The relationship between numbers in the accounting equation

The accounting equation states that Assets (A) = Capital (C) + Liabilities (L). Such an equation, which can also be abbreviated as A = C + L, can be stated in financial terms for a particular business at a particular time:

£100,000 of Assets (A) = £80,000 of Capital (C) + £20,000 of Liabilities (L)

The accounting equation can be expressed in the different forms below, which are all correct for the example of our business with assets of £100,000:

A = C + L or £100,000 = £80,000 + £20,000 (accounting equation)

C + L = A or £80,000 + £20,000 = £100,000

C = A - L or £80,000 = £100,000 - £20,000

L = A - C or £20,000 = £100,000 - £80,000

A – L = C or £100,000 - £20,000 = £80,000

A – C = L or £100,000 - £80,000 = £20,000

The simple equation of 3 + 2 = 5 is true as long as each of the three numbers does not change. If one number is hidden, as long as the other two numbers are known in our example, then the hidden third number can be worked out easily. For example, if ‘3’ is hidden in 3 + 2 = 5, we know that this number must be 3 in order to make the equation true.

A special type of equation is an algebraic equation where a letter, say ‘x’, represents a number i.e. in x + 2 = 5, ‘x’ represents 3 in order to make the equation true.

Algebraic equations are solved by manipulating the equation so that the letter stands on its own. This is achieved in the equation x + 2 = 5 by the following two steps.

x = 5 – 2

x = 3

The principal rule of manipulating equations is whatever is done to one side of the equal side must also be done to the other as was shown in step 1 above i.e.:

x = 5 – 2 is achieved by subtracting 2 from both sides of the equation x + 2 = 5 i.e.

x + 2 - 2 = 5 – 2

x = 3

Manipulating an equation to get the algebraic letter to stand on its own involves ‘undoing’ the equation by using the inverse or opposite of the original operation. In the example of x + 2 = 5, the operation of adding 2 must be undone by subtracting 2 from either side of the equal sign.

The following table shows a number of examples of how equations are manipulated to solve the correct number for the algebraic letter.

| Operation | Inverse | Equation | Manipulation to solve algebraic letter |

| add 7 | subtract 7 | a + 7 = 9 | a + 7 - 7 = 9 – 7 a = 2 |

| subtract 5 | add 5 | b - 5 = 6 | b – 5 + 5 = 6 + 5 b = 11 |

| multiply by 3 | divide by 3 (or multiply by 1/3) | c x 3 = 18 | c x 3 / 3 = 18 / 3 c = 6 |

| divide by 6 | multiply by 6 | d / 6 = 2 | d / 6 x 6 = 2 x 6 d = 12 |

An equation such as a x 3 = 12 can also be expressed as a3 = 12 or 3a = 12, i.e., if an algebraic letter is placed directly next to a number in an equation it means that the letter is to be multiplied by the number. (By convention, the number is always put before the letter i.e. 3a not a3).

The correct number for the algebraic letter ‘a’ in the equation 3a = 12 will be obtained thus:

3a = 12

3a / 3 = 12 / 3

a = 4

2.11.1 Manipulation of formulae

Manipulating or rearranging formulae involves the same process as manipulating or rearranging equations.

In the formula S = D / T, S is the subject of the formula. (This simply means that S stands on its own and is determined by the other parts of the formula. By convention the subject is always placed on the left-hand side of the equal sign, although S = D / T means the same as D / T = S)

To rearrange or manipulate an equation, the formula S = D / T can also be manipulated to make D or T the subject.

S = D / T

D / T = S (turning the formula around)

D = S x T (multiplying both sides of the formula by T)

Or, from D = S x T

D / S = T (dividing both sides of the formula by S)

T = D / S (turning the formula around)

Box 6 An important note about formulae

A formula is simply an equation that states a fact or rule, such as S = D / T or Speed is equal to Distance divided by Time. The accounting equation you will learn about in Week 3, although always described as an ‘equation’ by convention, could be more accurately described as the ‘accounting formula.’

Activity 10 Use of equations and formulae

Part A

Solve the following algebraic equations:

c + 9 = 11

Answer

c = 2

a - 15 = 21

Answer

a = 36

d x 7 = 63

Answer

d = 9

b / 13 = 13

Answer

b = 169

Part B

Rearrange the formula h = 3dy - r to make:

r the subject

Answer

h = 3dy - r

h + r = 3dy

r = 3dy – h

y the subject

Answer

h = 3dy - r

h + r = 3dy

3dy = h + r

y = (h + r) / 3d (Did you remember to use brackets?)

Summary of Week 2

A competent accountant should have the confidence and ability, both mentally and using a calculator, to be able to add, subtract, multiply, divide as well as use decimals, fractions and percentages. Completing tables of equivalencies is a good way of practising converting between percentages, decimals and fractions. All accountants should be able to manipulate simple equations and formulae. The most important equation in accounting is the accounting equation, which states that Assets (A) = Capital (C) + Liabilities (L).

You can now go to Week 3: Double-entry accounting.

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Jonathan Winship.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2015 The Open University