Dutch painting of the Golden Age

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 24 April 2024, 8:49 PM

Dutch painting of the Golden Age

Introduction

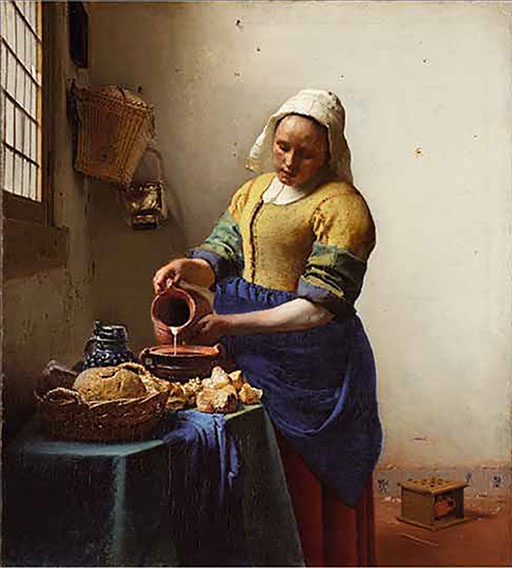

In this free course, Dutch painting of the Golden Age, you shall be exploring issues of meaning and interpretation with specific reference to Dutch seventeenth-century painting. Works by artists such as Johannes Vermeer (Figure 1), Pieter de Hooch (Figure 2), Gabriel Metsu (Figure 3), Jacob van Ruisdael (Figure 4) and Jan Steen (Figure 5) are now among the best-known and most admired possessions of major public collections. Unlike elaborate decorative schemes or complex mythological subjects, these comparatively small-scale paintings appear to require little prior knowledge on the part of the viewer. We have no difficulty making out the scene that is represented and although the costumes and setting may be unfamiliar, we are offered a view on to a world that is recognisably continuous with our own. Even where an artist depicts activities that belong to a different era, such as the bleaching of cloth in the fields surrounding the city of Haarlem (Figure 4), this simply adds a further element of interest and value. It is therefore perhaps surprising to learn that there has been vigorous debate among art historians about the possible meanings that might be attributed to these paintings and that there is, as yet, no consensus as to the correct approach to interpreting the wide range of images that were produced in the Netherlands in its socalled ‘golden age’. As you shall see, much of the debate has centred on the purported realism of these paintings and the highly problematic assumption that they provide a comprehensive ‘pictorial record’ of life in the Dutch Republic (Slive, 1995, p. 1).

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A226 Exploring art and visual culture.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

explore recent debates around the interpretation of seventeenth-century Dutch painting

consider the strengths and limitations of iconology as an art-historical approach

examine the notion of ‘realism’ as applied to works of art

address the relevance of social and cultural context for interpreting works of art

analyse works of art in terms of different ideas and approaches.

1 ‘A new state, a new art’

The political and geographical entity that has come to be known as the Netherlands – and more popularly, although incorrectly, as Holland – emerged through a protracted struggle to gain independence from Spain. A confederation of Northern Provinces came together in 1579 in order to resist Habsburg rule, but it was not until the signing of a truce in 1609 and then the peace of the Treaty of Münster in 1648 that the Dutch Republic gained official recognition as a sovereign state. The early years of the seventeenth century are generally seen to mark the beginning of the Dutch golden age, when this small area of northern Europe became a flourishing centre of trade, shipping and finance, and made significant contributions to the domains of science, technology and culture. Through its large naval fleet, the Dutch Republic dominated world trade and established extensive colonial holdings, which formed the basis of its great wealth and power.

Two defining features served to distinguish the Dutch Republic from the predominantly Catholic and absolutist structures of neighbouring European powers. First, although a central administrative body was established in The Hague, each of the Provinces that made up the Netherlands was largely self-governing, allowing for greater independence and the development of strong local identities and traditions, particularly in large cities such as Amsterdam, Utrecht, Leiden, Haarlem and Delft. While agriculture and livestock remained important, it was a predominantly urban society, with a dense network of canals connecting the major trading centres. Second, Protestant Calvinism rather than Catholicism was adopted as the state religion. Since Calvinist theology prohibited the use of images in churches and other places of worship – though not in secular buildings such as homes or civic buildings – this had a significant impact on the forms of art that were produced. By contrast with Rome, and indeed most other European centres of art at the time, where artists could hope to gain substantial commissions from the church or the state, and were more or less dependent on aristocratic patrons, the Netherlands was a highly commercialised society that supported a growing independent art market. This is one reason why portable easel-painting, rather than more costly media such as sculpture or grand architectural projects, became the dominant form of visual art in the Netherlands.

It has been estimated that in the twenty-year period from 1640 to 1659 alone, between 1.3 and 1.4 million paintings were produced in the Netherlands – a remarkable figure given that the population at mid-century numbered approximately 2 million. Contemporary reports describe large numbers of paintings on display even in relatively modest households, and inventories show that oil paintings were well within the reach of the broad middlestrata of Dutch citizens, costing in some cases less than household linen or a piece of furniture (Grijzenhout and van Veen, 1999, p. 1). One consequence of the development of an open market, in which artists had to find buyers for their work, was an increase in specialisation. By concentrating on a particular subject, such as landscape or still life, or even the representation of a particular type of animal or fabric, artists could carve out a reputation and occupy a profitable niche. The troubling effect that such specialisation had on later viewers can be discerned in the observations of the president of the British Royal Academy of Arts, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), in his Journey to Flanders and Holland of 1781:

Two fine pictures of Terburg; the white sattin remarkably well-painted. He seldom omitted to introduce a piece of white sattin in his pictures.

Dead swans by Weeninx, as fine as possible. I suppose we did not see less than twenty pictures of dead swans by this painter.

The two artists Reynolds identifies are Jan Weenix (Figure 6) and Gerard ter Borch (Figures 7–9). Weenix (1621–?1660/61) specialised in game birds rather than swans exclusively – Figure 6 shows a very fine painting of a dead partridge – and he also produced paintings depicting human figures. However, both artists do seem to have sought, wherever possible, to choose subjects that allowed them to display their virtuosity in their chosen field.

While Reynolds admires the level of artistry and technical accomplishment to be found in the work of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, he notes that ‘their merit often consists in truth of representation alone’ and that it ‘is to the eye only that the works of this school are addressed’ (Alpers, 1983, p. xviii). The implicit contrast here is to painting in the ‘grand style’ associated with the Italian Renaissance and sustained through the teaching and patronage of state-sponsored Academies of Art across Europe. A central tenet of academic art theory, which Reynolds did much to promote, was that artists should demonstrate a capacity for ‘invention’ and ‘design’ by depicting elevated subjects derived from biblical, historical and mythological sources – capacities that were valued more highly than the ‘mechanical’ skill of imitation. Like others who adhered to this classicist and idealising conception of art, Reynolds measured Dutch painting against the expectations derived from a different tradition and found it wanting. What troubles him is not simply its sheer abundance and apparent repetitiveness, but what he sees as its merely imitative character.

It was not until the nineteenth century that a more positive evaluation of Dutch art began to emerge. When the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831) gave a series of lectures on aesthetics in Berlin in the 1820s he drew a close connection between the social and political emancipation of the Dutch Republic, emphasising the ‘overcoming of the Spanish despotism of church and crown’, and the development of a new form of art that was rooted in the activities and accomplishments of its citizens. Hegel contends that the ‘final achievement’ of Dutch painting lies in ‘its utterly living absorption in the world and its daily life’ and that we should therefore not ‘suppose that they should have avoided such subjects and portrayed only Greek gods, myths, and fables, or the Madonna, the Crucifixion, martyrs, Popes, saints male or female’ (Hegel, 1975, pp. 884−5). Like Reynolds, Hegel is fascinated by the detailed attention that Dutch artists bestowed on the visual appearance of even the most mundane objects:

Velvet, metallic lustre, light, horses, servants, old women, peasants blowing smoke from cutty pipes, the glitter of wine in a transparent glass, chaps in dirty jackets playing with old cards – these and hundreds of other things are brought before our eyes in these pictures, things that we scarcely bother about in daily life.

Rather than decrying the apparently vulgar or trivial nature of such preoccupations, Hegel interprets the turn towards contemporary subjects as an expression of pride in Dutch citizenship and the hard-won freedoms of civil society.

Hegel gives his argument an unexpected twist by making a further observation that came to play an important role in later accounts. He notes that when we look at depictions of everyday scenes, the very prosaic and apparently insignificant character of the subject matter can help to draw our attention to the manner in which the painting has been produced and thus to the artist’s technical skill in rendering appearances. We are made more insistently aware of the art of painting as something that is valuable in its own right. Hegel puts this by saying that what enchants us ‘is not the subject of the painting and its lifelikeness’, but rather ‘the pure appearance which is wholly without the sort of interest that the subject has’ (Hegel, 1975, p. 598). In more straightforward terms, we might say that our interest in the painting is not identical with our interest in what it depicts. The depiction of a white satin dress, such as we find in The Paternal Admonition (Figure 7) and Curiosity (Figure 8) by Gerard ter Borch (1617–81) engages our attention in ways that things in the world do not, for we admire not merely the lustre of the material and the way that it reflects the light, but also the artist’s ability to capture these effects in the medium of paint. Hegel speaks of ‘the existent and fleeting appearance of nature as something generated afresh by man’, thereby drawing attention to the fact that a depicted object such as a wine glass or a satin dress is made twice over, once by the maker and once by the artist (Hegel, 1975, p. 162). The painting, too, is an ‘appearance’, which owes its existence to the artist’s deployment of the resources of his medium, and we can take pleasure in this independently of what it represents.

Many of Hegel’s arguments were recast in more accessible form by the French artist and critic Eugène Fromentin (1820–76), who published a highly influential account of Dutch seventeenth-century painting in his book Les Maîtres d’autrefois (The Masters of Past Time) in 1876. Under the slogan ‘a new state and a new art’, Fromentin celebrated the emergence of ‘a national and free school of painting’, which liberated itself from foreign models and ‘ceased to borrow from Italy its style and poetry, its taste for history, for mythology and for the Christian legends’ (Fromentin, 1948 [1876], p. 91, 95 and 98). According to Fromentin, we need to recognise the close connection between art and society if we are to appreciate the distinctive character of Dutch seventeenth-century painting:

The revolution which had just made the Dutch people free, rich and so ready to undertake everything, stripped them of that which everywhere else made up the vital element of the great schools … Dutch painting, as one very soon perceives, was not and could not be anything but the portrait of Holland, its external image, faithful, exact, complete, lifelike, without any adornment. The portrait of men and places, of bourgeois customs, of squares, streets, and countryside, of sea and sky – such was bound to be, reduced to its primary elements, the programme adopted by the Dutch School; and such it was, from its first day until its decline.

Here we have a clear statement of the view that what distinguishes Dutch painting from other traditions is its realism. Fromentin characterises Dutch painting as a ‘portrait’ of urban and rural life in the Netherlands and claims that it provides us with an ‘external image’ that is ‘faithful, exact, complete, life-like, without any adornment’ (Fromentin, 1948 [1876], p. 97). The art historian Svetlana Alpers, whose ideas shall be discussed later in this course, has drawn attention to the underlying convergence between Fromentin’s views and those of Reynolds: although they differ in their evaluation of Dutch painting, both agree that its character is primarily descriptive (Alpers, 1983, p. xvii). What Reynolds criticises, Fromentin praises. It seems likely that Fromentin’s admiration for this aspect of Dutch art was informed by recent developments in French painting and the development of a nineteenth-century school of realist painters, foremost among them Gustave Courbet (1819–77). Although Fromentin and Reynolds adhere to very different notions of art, and thus offer contrasting valuations of the significance of Dutch seventeenth-century painting, their accounts coincide in emphasising its ostensible ‘truthfulness’ and lack of idealisation.

2 Realism and art-for-art’s sake

From the late nineteenth century through to the mid twentieth century, it was widely accepted among art historians that Dutch painting of the golden age was distinguished from other national traditions by its realism. Thus, for example, the German art historian Wilhelm Bode, in his 1883 Studien zur Geschichte der holländischen Malerei (Studies in the History of Dutch Painting), declared: ‘It is evident that the fundamental tendency of this painting is above all realistic.’ (Bode, 1883) Realism here seems to have meant two different but closely related things. On the one hand, the term was used to describe the choice of subject matter taken from everyday life, such as domestic and tavern scenes, rather than classical or mythological subjects. Here realism is a matter of what is represented. On the other hand, the term was used to characterise a form of painting that purportedly offered a more truthful or exact imitation of visual appearances. Here realism serves to identify how an object or scene is represented (Białostocki, 1984). Although these two forms of realism frequently appear together, there is no necessary connection between them: it is possible to produce an idealised image of a street urchin (such as those painted by the seventeenth-century Spanish artist Murillo), just as it is possible to produce a realistic image of a king. However, the double meaning of the term allowed art historians to extend its use to accommodate a broad spectrum of Dutch paintings. The subject of ter Borch’s Boy Delousing a Dog (Figure 9) could not be further removed from the elaborate display of finery in his Curiosity (Figure 8), but the capacious term ‘realism’ allowed the one to be praised for its humble subject matter and the other for the verisimilitude, or truthfulness, with which the artist has rendered the textures of different fabrics and materials.

We have already seen that for Hegel the turn away from religious, historical and mythological subjects towards scenes of everyday life is closely allied to an interest in painting for its own sake – as if artists were liberated to pursue their own preoccupations by no longer having to depict weighty and important themes. This view is at variance with other conceptions of realism that took hold in the mid to late nineteenth century, which tended to emphasise the overriding importance of the artist’s social and political concerns and hence the incompatibility of realism with the notion of art-for-art’s sake. Despite the example of an artist like Courbet, whose work combines realism with political commitment, Hegel’s ideas seem to have struck a chord with Fromentin, who, if anything, provides an even more radical version of his argument. Fromentin contends that ‘the great Dutch school seemed to think of nothing but painting well’ and that it is characterised by ‘the total absence of what today we call a subject’ (Fromentin, E., 1948 [1876], p. 108). Here the term ‘subject’ doesn’t simply mean the painting’s depicted content but rather the moral, emotional or intellectual message that it is intended to convey. Fromentin is pointing up a contrast between the requirements of academic history painting, in which the artist was expected to depict noble and heroic individuals engaged in actions of emotional or intellectual significance, and the mundane and seemingly inconsequential incidents and events depicted in many Dutch paintings, among which he lists ‘drinking, smoking, dancing, kissing the maids’ (Fromentin, E., 1948 [1876], p. 112).

Fromentin contends that rather than looking for any deeper meaning we should recognise that these paintings are valuable first and foremost as art and that the quality of a painting is therefore independent of the subject that is represented:

What motive had a Dutch painter in painting a picture? None. And notice that he never asked for one. A peasant with a drunken red nose looks at you with his heavy eye and laughs with open mouth showing his teeth, raising a jug; if it is well painted, it has its value.

It is not clear whether Fromentin had any particular painting in mind when he wrote this passage, but it may be useful to consider it alongside a work by Adriaen van Ostade (Figure 10). Ostade (1610–85) specialised in the depiction of peasants drinking, merry-making and fighting, both out of doors and in dimly lit interiors (Figure 11). Despite a tendency towards caricature in the treatment of the figures, his work is characterised by subtle chiaroscuro effects and a remarkably delicate use of colour. Paintings such as these raise interesting questions about their intended audience and how they might have been viewed at the time. One possibility is that the intensive urbanisation of Dutch society created a market for images of rural life, including the imagined ‘freedoms’ that were permitted outside the more tightly regulated civic environment. However, it also seems likely that they catered to an urban disdain towards humble rural folk and thus served to reinforce the self-perception of city dwellers as more cultivated and sophisticated than those who lived in the countryside. This ambiguity is central to the significance of paintings of rural life in seventeenth-century Holland, which were largely purchased by those who had left this life behind.

3 Dutch history painting

Nineteenth-century Dutch nationalism helped to shape a canon based on the idea that authentically Dutch art is realist, allowing artists such as Johannes Vermeer (1632–75) (Figures 1, 29 and 30) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–84) (Figure 2) to be admired precisely on account of what is seen as their typically Dutch realism. Until comparatively recently art historians paid little attention to paintings produced in the Netherlands that could not be subsumed under the twin rubric of ‘realism’ and ‘art-for-art’s sake’. It is important to recognise, however, that schools of Italianate and classical painting continued to flourish in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century and that Dutch artists also depicted historical and mythological scenes. The Judgement of Paris by Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638) (Figure 12), which hangs in the same rooms of London’s National Gallery as works by Vermeer and de Hooch, is a good example of what is termed Dutch ‘mannerism’. Style labels such as this have to be applied with caution but there are marked differences in both subject matter and treatment that distinguish Wtewael’s painting from the more familiar examples of Dutch art that have been discussed so far. The term ‘mannerism’ is employed here to identify a self-consciously refined and artificial manner of painting (maniera) whose origins can be traced back to sixteenth-century Italian art. Another important school of artists based in Utrecht, a bishop’s seat with strong links to Rome, became known as the Caravaggisti because of their indebtedness to the work of the Italian artist Caravaggio (1571–1610). The Concert (Figure 13), by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629), also in the National Gallery, employs dramatic light effects to explore the contrast between areas of bright illumination and deep shadow. The tendency of art historians up until recent decades to marginalise these works or to treat them as somehow insufficiently ‘Dutch’ was corrected by an important exhibition entitled Gods, Saints and Heroes: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt which was shown in both America and the Netherlands in 1981 (Blankert, 1980).

It is noteworthy that in order to establish his claims concerning the appearance of ‘a double and very concordant product – a new state and a new art’, Fromentin was obliged to characterise Rembrandt (1606–69) as ‘an exception in his own country and everywhere else’ (Fromentin, 1948 [1876], p. 91). Rembrandt’s extraordinary range as an artist makes him hard to categorise under any schema, but the difficulty of extending the realist interpretation to accommodate a work such as Belshazzar’s Feast (Figure 14) – which combines careful attention to the play of light over different textures and surfaces with the dramatic re-imagining of a story taken from the Old Testament – should give us pause for thought. The re-assessment of Dutch art that has taken place in recent years has opened up the field of study to include the full range of subjects, themes and types of painting that were made and purchased in the Netherlands. However, the main challenge to the realist interpretation came not from this more inclusive approach but from the development of an alternative way of understanding the small-scale paintings of domestic scenes and unprepossessing tracts of land on which Hegel and Fromentin had focused their attention.

4 Disguised symbolism and ‘seeming realism’

Doubts about the validity of the realist interpretation had already been expressed in scattered form by a number of writers, but it was not until the completion of the so-called ‘iconological turn’ in Dutch art history in the second half of the twentieth century that a viable alternative was established. Iconologists are primarily concerned with the content or subject matter of an artwork rather than its style or technique, and they draw on a wide range of sources, including contemporary writings and documents, in order to elucidate the significance of particular subjects and motifs. The leading proponent of the use of this approach to elucidate Dutch seventeenth-century painting, Eddy de Jongh, defines iconology as ‘the branch of art history that seeks to explain the content of representations in their historical context, in relation to other cultural phenomena and to specific ideas’ (Jongh, 1999, p. 200). However, the key difference from both realist and art-for-art’s sake approaches is best captured in his observation that the iconologist ‘sees works of art as vehicles of meaning’ (Jongh, 1999, p. 200).

The modern use of the term ‘iconology’ derives from the work of the art historian Erwin Panofsky, whose book Studies in Iconology was published in 1939 (Panofsky, 1972 [1939]). He originally developed iconology as a tool for interpreting Renaissance art, which provided rich material for the detection and decoding of symbolic and allegorical concepts. However, in his book Early Netherlandish Painting (1953) he sought to show that iconology could also be applied to northern art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, despite its outwardly naturalistic appearance. Panofsky introduced the idea of ‘disguised symbolism’ to explain how apparently realistic representations of everyday objects and motifs, such as flowers, fountains and enclosed gardens, could take on symbolic significance, standing for example as symbols of the Virgin’s purity. It was de Jongh, however, who first extended this approach to the study of seventeenth-century Dutch painting, which had previously seemed so recalcitrant to any search for deeper meanings.

In accordance with the requirement cited above that the iconologist should place artworks in their original ‘historical context’ and draw on ‘other cultural ideas’ to explain their content, de Jongh drew attention to two important features of seventeenth-century Dutch culture. First, he observed that in this predominantly Calvinist society there was a pervasive tendency to moralise, expressed through exhortations to live a virtuous life and reminders of the transience of worldly pleasures. Second, he drew attention to a wide range of literary and other sources that delighted in word play, metaphor, riddles and rebuses. This allowed him to suggest that there was a ‘marked preference for disguising, veiling, allegory, and ambiguity, in short, for all that is enigmatic’, and that this could also be found in seventeenth-century painting (Jongh, 1971, p. 21). Of particular significance for his account is the great popularity of emblem books, a form of illustrated literature in which images of everyday objects and other motifs were given multiple interpretations through the addition of mottos and poems that expounded a diversity of possible meanings. Jacob Cats (1577–1660), one of the most widely read authors of such works, wrote of the ‘agreeable obscurity’ that arises when a maxim or proverb appears to mean one thing but in reality contains another, claiming that ‘Experience teaches us that many things gain by not being completely seen, but somewhat veiled and concealed.’

By putting these two things together – the moralising tendency of Dutch society and the predilection for hidden or covert meanings – de Jongh developed a new framework for interpreting Dutch seventeenth century painting. His core thesis is that rather than offering a ‘reflection of reality’, as the realist account supposes, Dutch paintings of this period contain only a ‘seeming realism’. The Dutch term he uses is schijnrealisme, which might also be translated as the ‘semblance’ or ‘mere appearance of realism’. According to de Jongh, schijnrealisme ‘refers to representations which, although they imitate reality in terms of form, simultaneously convey a realized abstraction’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 21). What he means by this is that although the outward appearance of a painting might provide a realistic representation of, say, figures in a domestic interior, this can be used to communicate abstract ideas, which the viewer grasps by interpreting the painting’s symbolic or allegorical content. The painting appears to be a representation of an everyday scene, but it contains hidden meanings that the iconographer must seek to decode. The best way to understand this argument is to consider an example, which you will do so in the next section.

Clues to interpretation

We shall focus on Merry Company (Figure 15), a painting by the little-known Haarlem artist, Isaac Elias, dating from c.1620, since de Jongh presents his analysis of this painting as a ‘demonstration’ of his theory of seeming realism.

The painting depicts a group of figures engaged in a variety of activities, seated or standing around a table in a well-appointed interior. The title, Merry Company, would have been given at a later date, and is often used to describe paintings that show finely dressed people relaxing together, eating, drinking and sometimes playing music. De Jongh begins his analysis by drawing attention to the two paintings that are shown hanging on the wall behind the figures. These are difficult to make out in reproduction, and are of small size even in the original, but the rectangular picture on the left depicts the biblical theme of the Deluge and the oval picture on the right a battle scene. De Jongh describes the device of including a painting-within-the-painting as a traditional seventeenthcentury means of ‘admonishing’ the depicted figures. He notes that there is nothing ‘merry’ about these two images: the Deluge alludes to Divine punishment for the sinfulness of mankind, while the battle scene can be related to biblical texts that describe life on earth as a struggle or conflict in which our moral fortitudeis tested.

De Jongh’s second main contention is that there is an important difference between the two figures standing on the right and the other figures in the painting. He identifies them as a couple and observes that they do ‘not partake in the meal, but rather stand and look out of the picture plane toward the viewer’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 24). Once we note this difference, it is possible to interpret the scene beside them not as a realistic representation of figures who are in the same room as them at the same time, but as an allegorical representation of the temptations facing a wedded pair, who must use their resolve to ensure the virtuous conduct of their future life together. In particular, de Jongh claims that the diners in the painting are an allegory of the Five Senses of sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing, and that each of these would have been understood by contemporary viewers as symbolising various sinful possibilities. The diners function both as a ‘moral mirror’ and as ‘hidden persuaders’, who prompt the couple – and by extension the viewer – to resist the seduction of worldly pleasures.

In support of this interpretation, de Jongh observes that whereas in other countries ‘allegorical concepts were almost always cloaked in the form of fantastical personifications, in Holland they generally appeared as “normal” people in everyday garb’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 21). The meanings of such paintings are thus ‘hidden’ in a double sense. On the one hand, they were veiled or disguised for contemporary viewers, who were expected to use clues within the painting, such as the pictures on the wall, to work out the moral message. On the other hand, they are hidden in a second and stronger sense from later viewers, who take Dutch paintings to be straightforwardly ‘realistic’ depictions of scenes from everyday life.

Once the viewer is alert to the possibility of hidden meanings, even familiar paintings can start to look very different. Some art historians have suggested that we need to look for a clavis interpretandi or ‘key to interpretation’, which is often tucked away in a remote corner. A particularly telling example is given by de Jongh in his analysis of a painting by Jan Steen (1626–79), which he refers to by the title The So-Called Brewery of Jan Steen (Figure 16).

Activity 1

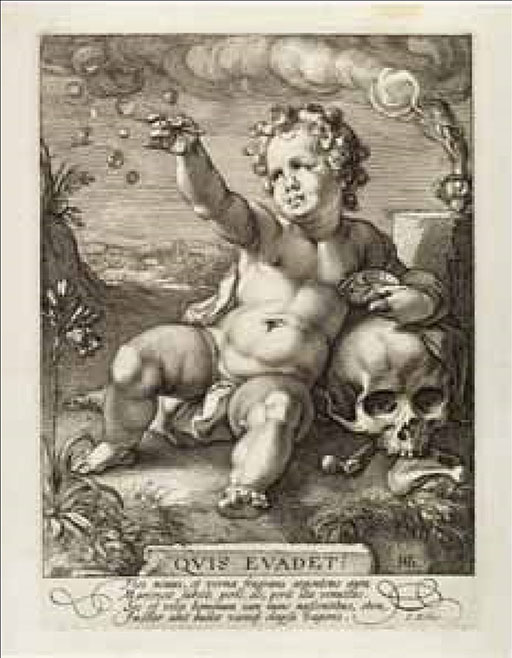

Look carefully at the reproduction of this painting in Figure 16 and say what you think the subject of the painting might be. Then look at Figure 17, which shows a detail of the painting in which a boy, tucked away in the loft, blows bubbles next to a skull. What meaning might be attributed to this motif and how might this influence your interpretation of the painting?

Discussion

The painting depicts a spacious interior, illuminated by a window to the left, in which several groups of people are engaged in various activities. It looks more like a room in a domestic house than a brewery (the title may have been given because Jan Steen’s father was a brewer and the painter himself for a short time ran a brewery). However, the room is very large by modern standards and it is crowded with figures who are shown relaxing with music, food and other diversions. On the left, there is a seated man eating oysters, more of which are being prepared by a young woman in the foreground. On the right are figures seated at a table, including a woman singing with an oyster in her left hand, and a lute player half turned towards her. The composition of the painting encourages us to move from one group of figures to another to discover what each is doing, and we are rewarded by plenty of incidental detail, such as the boy encouraging a cat to ‘dance’ on its hind legs. It would seem, then, that the subject of the painting is merry-making in one form or another, and that we are offered a view of Dutch citizens contentedly fulfilling their hours of leisure. The boy blowing bubbles in the upper storey seems fully continuous with this theme until we notice the skull beside him. In western painting, the incorporation of a skull into a picture often serves as a memento mori, a ‘memento of death’, which reminds the viewer of the transience of worldly pleasures. The presence of this overtly symbolic motif suggests that the painting may not be a straightforwardly ‘realistic’ representation of an everyday scene and alerts us to the possibility that it may contain a moral dimension.

In his discussion of this painting, de Jongh argues that the depiction of the boy blowing bubbles is closely linked to the memento mori theme. He interprets it as a visual representation of the Latin phrase homo bulla, ‘man is [fragile] as a soap bubble’: just as a bubble floats into the air and catches the radiance of light, only to burst into nothing, so human life is brief and evanescent. The location of this image near the centre of the painting, at a point where several lines converge, gives credence to de Jongh’s proposal that Steen has provided us with a necessary clue to interpret the painting. The prevalence of this image in other paintings and in emblem books and engravings, where its meaning was sometimes made explicit through textual commentary (Figure 18), suggests that contemporary viewers would have been able to discover this clue. De Jongh also points out that oysters, which were thought to be an aphrodisiac, were popularly associated with licentiousness, and that the female figure standing by the window is probably a matchmaker carrying out her trade. He therefore concludes that the subject of the painting is contained in its moralising message: it condemns the frivolousness of the various pastimes it depicts.

De Jongh’s analysis is open to challenge. In particular, it is curiously at variance with the mood of the picture and the lively way in which the artist has painted such a busy scene crammed with life. However, whether or not one agrees with his conclusions, his approach successfully draws attention to the artificiality of the representation. We are led to wonder why certain objects, such as cups and a spoon, are scattered on the floor and whether a milk pail would have been left standing unattended where it could easily be knocked over. It is as if each object or figure in the painting has been carefully placed to invite interpretation and is thus the result of deliberation by the artist rather than a reflection of the haphazard contingencies of a ‘slice of life’. Most striking of all is the large piece of cloth draped over the balcony, which can be read both as a naturalistic representation of an object within the depicted scene and as a curtain in front of the painting that is pulled up in a theatrical way to reveal what lies behind.

Having looked closely at this painting by Jan Steen, we can now return to his The Effects of Intemperance (Figure 5). What initially appears to be a ‘realistic’ image of a scene from everyday life turns out to be full of artful contrivances. That the woman’s slumber is caused by the effects of alcohol is suggested by the image of the girl encouraging a parrot to drink from a wine glass. The resulting disorder is illustrated through the small child picking the woman’s pocket as she sleeps and the older children feeding a pie to the cat. The pig standing before a rose refers to a Dutch proverb about tossing roses before a swine, whose meaning is analogous to the English proverb ‘pearls before swine’. Above the woman’s head hangs a basket, which contains a birch switch, a crutch and a leper’s clapper, objects associated with punishment, infirmity and disease. In this case, it seems clear that the painting does contain a moral message or, at least, takes moral themes as part of its subject matter. Although the clues to interpretation can scarcely be said to be ‘hidden’, the baleful consequences of intemperance are shown through everyday actions and objects such as might have been seen at the time Steen was painting rather than through ‘fantastical personifications’ based on classical mythology.

So far we have only considered examples of interior and exterior scenes with multiple figures. However, de Jongh contends that his analysis of the ‘seeming realism’ of Dutch seventeenth-century painting can also be applied to other types of painting, including portraiture, still life and landscape painting. Artists who specialised in ‘flower pictures’ depicted costly bouquets of rare and exotic flowers with the occasional addition of a stray butterfly or beetle. Although these bouquets look highly realistic, and seem to have been painted from life, they frequently include flowers that bloom at different times of the year and so could not have been seen together. De Jongh contends that flower pictures would have been understood in relation to contemporary mottos such as Sic transit gloria mundi (‘So passes away the glory of the world’) and were intended to evoke an awareness of transience. In support of this contention he draws attention to the figure and inscription embossed on the terracotta pot depicted in Jan van Huysum’s Flower Still Life (Figure 19). This contains part of a verse from Matthew 6, ‘Consider the lilies of the field; even Solomon in his glory was not arrayed like one of these.’ However, de Jongh notes that such overt references were unusual and that ‘symbolism in seventeenth-century flower pieces is usually cloaked in a realistic disguise’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 29). He contends that even without the presence of a ‘key to interpretation’, such as van Huysum provides, educated contemporary viewers would have been expected to grasp the connection between the ephemeral beauty of flowers and the brevity of human life. De Jongh’s account of the deeper significance accorded to flower paintings is at variance with the low evaluation accorded to still-life painting within the academic hierarchy of the genres, which was still upheld by Reynolds when he travelled to Holland. We might also ask whether there may have been other, less weighty reasons why affluent city dwellers wanted to place images of flowers on their walls. Horticulture was highly developed in the densely urbanised Netherlands and flowers such as tulips were greatly prized and sought-after.

5 ‘To instruct and delight’

The iconographic method rapidly established itself as the dominant approach to seventeenth-century Dutch painting and was taken up by a large number of art historians, both in the Netherlands and elsewhere. In 1976, exactly one hundred years after the publication of Fromentin’s book, de Jongh and his colleagues curated a major exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, to which they gave the title Tot Lering en Vermaak (‘To instruct and delight’). In the wall captions and the accompanying catalogue, they sought to show that by placing familiar artworks in their original historical context, and by drawing on a wide range of contemporary literary sources, it was possible to discern ‘hidden meanings’ that had previously been overlooked or lost from view. These hidden meanings were principally of a moral or didactic nature, and could be related directly to Calvinist teachings on virtuous conduct and the need to reflect on the transience of worldly goods. The curators claimed that the seductively pleasing appearance of Dutch paintings cloaked an important moral message and that they were intended not only to ‘delight’ the eye but also to ‘instruct’ the mind. The title of the exhibition can thus be taken as a radically different answer to the question that Fromentin had put one hundred years earlier. When Fromentin asked ‘what motive had a Dutch painter in painting a picture?’, he answered ‘None’. De Jongh and his colleagues claimed that there was a motive: to instruct and delight.

The contrast between these two approaches becomes all the more marked when we observe that the iconographic method is deeply rooted in the humanist tradition of classical learning. The motto ‘to instruct and delight’ derives from the Latin docere et delectare and the sentiment it embodies can be traced back to the declaration by the Roman poet Horace (65 BCE–8 CE): Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci (‘He who unites the useful with the pleasant is praised’). Moreover, the identification of a close connection between textual and visual sources was a mainstay of classicist art theory, which frequently referred to the idea of the ‘sister arts’ expressed in Horace’s dictum ut pictura poesis (‘as is a picture, so is a poem’). Whereas the nineteenth-century realist and art-for-art’s sake interpretation emphasised the ‘new’ character of Dutch art and society, insisting that the urban and commercial nature of the Netherlands made it unlike other cultures, the iconographic method reintegrated the study of Dutch painting into mainstream art history. For the art historian who seeks to track down recondite allusions and decipher visual puzzles by studying paintings alongside literary texts and documents, the extension of iconography to seventeenth-century Dutch art allows a return to business as normal.

You will now consider some of the criticisms to which the ‘disguised symbolism’ interpretation is exposed. The main focus of the discussion will be on landscape painting, since it is here that the most interesting debates have been generated.

6 Landscape painting and the limitations of the iconological approach

When de Jongh first drew the distinction between ‘realism’ and ‘seeming realism’ in his landmark essay of 1971, he was careful to point out that while he had found evidence of disguised symbolism in all the main types of Dutch seventeenth-century painting, including interior scenes, still life, portraiture and landscape, it would be wrong to assume that every painting of this period was ‘infused’ with hidden meanings. Other art historians have suggested that there may have been different degrees of disguised symbolism: whereas some artists, such as Jan Steen, made overt reference to moralising Dutch proverbs and emblem books, other artists, such as Vermeer, cloaked their ideas in forms that are harder to decode (Renger, 1978, pp. 12–13). However, given the extraordinarily varied and wide-range of subjects to be found in Dutch seventeenth-century painting, the question arises whether it is plausible to assume that artists working in different places and in different genres over such a long period could have been involved in the same basic enterprise. As Mariët Westermann puts it:

Could all these very different pictures, made by different hands, in very different styles, for very different eyes, possibly come down to the same moral essence? Were that plausible … was there nothing to distinguish these paintings, as paintings, from the prints, emblems, plays, treatises, and sermons used to gloss them?

The iconographic method is thus potentially reductive in at least two senses: not only does it presuppose that the great variety of Dutch painting possesses the same basic moralising content – itself often reducible to familiar homilies about the transience of worldly pleasures – it also appears to limit the interest we take in such paintings to their hidden moral message. In so far as the ‘meaning’ of a painting is treated as something that can be isolated from the form in which it is expressed, the painting itself becomes little more than a ‘vehicle’ for communicating ideas that could readily be found elsewhere. The iconographic method thus risks losing sight of those features of Dutch painting towhich Hegel had drawn attention, such as the artist’s ability to capture the play of light on different surfaces and the distinctive pleasure we take in the ‘appearance’ of an artwork. Although de Jongh and his colleagues claimed that the artist’s purpose was ‘to instruct and delight’, the iconographic method seems better equipped to explain the way in which a painting might ‘instruct’ the viewer rather than how it might serve as a source of pleasure.

A further problem with the disguised symbolism interpretation is that almost everything seems to be open to interpretation as a symbol of something else, making it very hard to determine whether a depiction of, say, a flower or rising smoke, was actually intended to be interpreted in a particular way. Consider, for example, the following passage from a book by the Dutch writer Levinus Lemnius published in 1587, in which he observes that a man’s life can be compared

to a Dreame, to a smoke, to a vapour, to a puffe of winde, to a shadow, to a bubble of water, to hay, to grasse, to an herb, to a flower, to a leafe, to a tale, to vanitie, to a weaver’s shuttle, to a winde, to dried stubble, to a post, to nothing.

Given this propensity to attribute symbolic meanings not only to natural phenomena (‘a puffe of winde’) but also to human inventions (‘a weaver’s shuttle’), it is possible that even paintings showing the most ordinary looking scenes might have been interpreted in symbolic terms. De Jongh, for example, suggests that Winter Landscape of 1624 by Esaias van de Velde (1587–1630) (Figure 20) refers to the ‘passage of the seasons’ and that ‘the waxing and waning of nature, could be seen as parallel to the course of man’s life from the cradle to the grave’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 27). His argument is not that we know for certain that the artist was inspired by this idea, but that we cannot exclude the possibility that contemporary viewers saw the painting in these terms: this realisation should give us pause for thought and prompt us to question the realist assumption that the painting is simply a faithful report of a scene viewed by the artist with no further significance.

De Jongh’s discussion of the ‘seeming realism’ of van de Velde’s Winter Landscape is carefully hedged with doubts and qualifications. By reminding the reader that seventeenth-century viewers may have been responsive to analogies and correspondences that are unfamiliar to us today, he provides an alternative interpretative framework that encourages us to consider the differences between the way in which we view the painting and the way it may have been viewed at the time. However, other art historians have applied the iconographic method to Dutch landscape paintings in a much more determinate way and have sought to identify a detailed programme of specifically religious symbols that can be decoded through reference to textual sources. The adoption of this approach by the art historian Joseph Bruyn in an essay published in the catalogue to an exhibition entitled Masters of Dutch Seventeenth-Century Landscape Painting, which was shown in both America and the Netherlands in 1988, awakened a great deal of controversy. For many art historians, Bruyn’s attempt to provide a ‘scriptural reading’ of landscape paintings by artists such as Jan van Goyen (1596–1656) and Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/29–82) proved a step too far, and it helped to stimulate critical reflection on the limits of the iconographical method.

As we might expect, Bruyn was able to identify plentiful textual sources in which, for example, a forest is presented as a symbol of sinful life or a river as a symbol of transitoriness. However, it is one thing to point to the prevalence of such symbols in treatises, sermons and emblem books, and another thing to establish that this provides the key to interpreting their appearance in a landscape painting. The theory seems to be self-confirming, for it is hard to conceive how any landscape painting could be produced that did not include things such as trees, rivers and hills, for these are the constituents of the landscape itself and thus always available for analysis in such terms.

Interpreting the Dutch landscape

We can bring these issues into focus by considering Bruyn’s analysis of two small landscapes by van Goyen: Farmhouses with Peasants, which is variously dated to 1630 or 1636 (Figure 21) and Landscape with Two Oaks of 1641 (Figure 22). These paintings belong to the so-called ‘tonal phase’ of Dutch landscape painting, characterised by the use of a restricted palette to depict unprepossessing tracts of land, including river scenes and the dune landscape by the coast, with its sandy soil, scarce vegetation and scattered human dwellings. Bruyn acknowledges that it ‘may come as a surprise to learn that van Goyen’s images dealt so often – or even as a rule – with the transience of a vain world’, but he goes on to identify a number of specific motifs that can be used to support this interpretation. In his account of Landscape with Two Oaks he claims that:

the weather-beaten trees are treated as protagonists, thus emphasizing their symbolization of vanitas. Equally clear is the meaning of the idle, chatting figures, and perhaps the interpretation of the horizon as the end of life, which appears in [a printed text by Jan] Luyken, could be applied to such a panorama. The traveller descending a hill with his back to the viewer might well be the pilgrim, approaching the church in the distance to the left.

Bruyn applies the same reading to Farmhouses with Peasants, arguing that the two tiny figures walking away from the farmhouses should be interpreted as pilgrims. Having noted that one of them carries a long stick with a sack, he observes that ‘It can hardly be fortuitous that the pilgrim on his life’s journey towards heavenly paradise was described during the late Middle Ages as carrying a sack containing his sins on his right shoulder.’ (Bruyn, 1987, p. 95) The weakness of this sort of interpretation lies not so much in the proposal that seventeenth-century viewers may have looked for religious symbolism even in apparently commonplace scenes, but in the way in which it isolates specific motifs from the painting as a whole, which is thereby reduced to a mere composite of elements that can already be found elsewhere. There is little interest in the painting as a painting or the way in which van Goyen has sought to communicate his own particular vision of the Dutch countryside.

In the same exhibition catalogue in which Bruyn’s essay appears, the historian Simon Schama offers a markedly different account of the possible meanings that these paintings may have had for contemporary viewers. Like Bruyn, Schama rejects the realist assumption that Dutch landscape paintings are simply an ‘arbitrary inventory of topographical data’ and both Schama and Bruyn are agreed that such images would have been interpreted in ways that may not be obvious to us today (Schama, 1987, p. 71). However, Schama is far more attentive to the innovative pictorial characteristics of early Dutch landscape painting, recognising that ‘these repeated images of sand, scrubby vegetation, bleak, wind-torn trees, and tattered dwellings’ are without precedent in the art of any other country. For Schama, the explanation for the development of this new type of painting, in which native scenes and habitats are depicted with great intimacy and feeling for locality, is to be found in Dutch patriotism and a ‘loyalty to the homely’ awakened by the vicissitudes of the early seventeenth century (Schama, 1987, p. 68 and 79).

The popularity of dune landscapes, which were also produced by other artists such as Pieter Molyn (1595–1661) and Salomon van Ruysdael (?1600/03–1670) (Figure 23), can be connected not only to the struggle for independence from Spanish rule, but also to the great land reclamation projects through which the Netherlands recovered substantial tracts of land from inland seas. Schama concludes that these paintings must be seen as ‘a highly selective and value-laden presentation of a particular kind of native habitat’ and that they testify to ‘the emergence of a native aesthetic, poetically expressed but normative in its associations’ (Schama, 1987, p. 71). In short, if we wish to discover the meanings that van Goyen’s work possessed for his contemporaries, we should look not – or not only – to the scriptural associations that might have been prompted by Calvinist theology, but also to the rise of Dutch nationalism and to the ‘political geography’ of a country in the process of self-formation.

7 The role of conventions

Schama’s approach represents a partial return to the position adopted by earlier writers such as Hegel and Fromentin, who drew a close connection between the emergence of the Dutch nation state and characteristic features of Dutch seventeenth-century painting. However, Schama’s recognition that the paintings he discusses are ‘highly selective and value-laden’ also accords with more recent studies that emphasise the role played by ‘conventions’ – or what we might term shared strategies of representation – in shaping both the form and the content of seventeenth-century Dutch paintings.

A remarkable study by the art historian Lawrence O. Goedde, in which he focused his attention exclusively on depictions of storms at sea and shipwrecks in Netherlandish art (Figure 24), revealed that out of the several hundred such pictures that still survive the vast majority conform to just six major types. According to Goedde, ‘Each type possesses a distinctive range of incident, setting, and weather and a characteristic treatment of composition and light, giving each a consistent range of expression and meaning.’ (Goedde, 1997, p. 129) In the paintings that Goedde examined, the same basic structures and motifs reappear again and again, suggesting that artists were working in accordance with a recognisable set of conventions that governed what could and, equally importantly, could not be represented. Moreover, by comparing the paintings with first-hand accounts of sea voyages and the numerous documents relating to maritime trade, he was able to demonstrate how much is not shown and how limited is the selection of suitable subjects.

The issue of selectivity casts further doubt on the ‘realism’ of Dutch art. Contemporary observers have noted the paucity of images that depict the Netherlands’ colonial exploits, even though this was one of the main sources of its trading and financial power. Paintings by artists such as Frans Post (1612–80) (Figure 25) and Albert Eckhout (1610–66), who travelled to the Netherlands’ colonies in Brazil, are an important exception, but here, too, artists seem to have relied on formulaic models to describe an unfamiliar environment. There are also surprisingly few paintings that record contemporary historical events, such as naval battles and other military conflicts. Despite his description of Dutch art as ‘the portrait of Holland, its external image, faithful, exact, complete, life-like’, Fromentin noted that although the country was involved in continual war in the seventeenth century, there is little trace of this in its painting (Fromentin, 1948 [1876], pp. 96–7 and pp. 109–11). More recently, Seymour Slive has written of ‘the false impression we get of life in the republic after the signing of the Peace of Münster if we derive it from celebrated Dutch paintings of tranquil domestic scenes’ (Slive, 1995, p. 3) . Once we recognise that pictures construct as well as reflect meaning, it is clear that, for all its apparent directness, Dutch seventeenth-century painting cannot be interpreted as a ‘neutral’ representation of contemporary life.

7.1 Landscape conventions and the question of meaning

Examination of the role of conventions in determining the content and format of Dutch paintings can also help us to identify the significance that may have been attached to the representation of particular subjects and motifs, and the ways in which artists modified existing forms of depiction in pursuit of new expressive possibilities. We shall conclude this discussion of landscape painting by comparing two paintings that depict the quintessentially Dutch subject of a windmill in a rural setting. Summer Landscape (Figure 26) by Adriaen van de Venne (1589–1662) is a pendant to his Winter Landscape (Figure 27); both are signed and dated 1614 by the artist. Venne’s painting pre-dates the ‘tonal phase’ of Dutch landscape painting, in which artists such as van Goyen employed a muted palette of browns, greys and greens, and it retains the bright sky and busy activity to be found in the work of earlier Dutch and Flemish landscape painters. Jacob van Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede (Figure 28), painted about 1668–70, belongs to the later, so-called ‘classical phase’, in which artists strove to achieve a grander and more monumental type of landscape painting.

Activity 2

Look carefully at the reproductions of van de Venne’s Summer Landscape (Figure 26) and Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk (Figure 28). Windmill at Wijk depicts a real place, the village of Wijk bij Duurstede on the river Lek as viewed from the south, but Ruisdael has altered the topography by omitting the Vrouwen Port (Women’s Gate), which would have been positioned where the three women walk. It is uncertain whether Summer Landscape also depicts an actual location; it appears to be a composite of elements, which the artist has fused together in the studio.

How would you characterise the features that the two paintings have in common and what would you say were the most important differences, bearing in mind the problems of meaning and interpretation discussed in this section?

Discussion

The most obvious shared feature is the prominence given to the windmill, which in both cases is seen from below and set against the sky. Moreover, in both paintings the viewpoint is located at a distance that allows the artist to show the windmill in relation to the surrounding landscape. The windmill in Ruisdael’s painting is built of stone, whereas the windmill in van de Venne’s painting appears to be made of wood. There is a great deal of activity in Summer Landscape: a beggar stretches his hand towards a wagon crossing a stream, on the left hunters are shown under trees and on the right a quarrel has broken out over a dropped basket of eggs. Windmill at Wijk also contains human figures, but the man on the platform of the mill and the three women walking beside the water provide little narrative interest. Attention is focused instead on the dramatic contrast between the solid form of the windmill and the vast expanse of the cloud-filled sky. In both paintings the motif of the windmill can be given a symbolic reading. Art historians might look to emblem books, sermons and other religious texts to discover a ‘hidden’ moral and religious significance, noting, for example, that the blades of a windmill form a cross and that the grinding of corn can be related to the Eucharist.

Rather than treating the windmill in isolation as a transplantable symbol it is important to examine the way it actually appears in each of the two paintings and its role within the expressive organisation of the image as a whole. In van de Venne’s Summer Landscape the windmill is integrated into a richly populated landscape in which emphasis is placed on the time of year and the characteristic human activities associated with it. By contrast, in Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk the windmill dominates the surrounding landscape, taking on a heroic, monumental quality that is reinforced by powerful oppositions of light and dark. Both paintings accord with the convention in Netherlandish painting of showing the windmill from a low viewpoint and both invite a wide range of different responses, ranging from awareness of nature’s providence and the rewards of human industry through to a more specific appreciation of the windmill’s contribution to Dutch prosperity and economic success. Contemporary viewers, especially among the predominantly urban population, whose experience of the countryside derived primarily from travel and excursion, could have found in these images a powerful assertion of Dutch nationalism. However, the presence of divergent and sometimes conflicting allusions and associations is resistant to any attempt to impose a single, determinate meaning.

8 Realism reconsidered

This course has argued that recent work on Dutch landscape painting reveals some of the limits of the icononological approach and that it redirects our attention once again to those aspects of Dutch art that so intrigued Hegel and Fromentin. An important difference is that scholars now place greater emphasis on the selective and constructed nature of the ‘realist’ dimension of Dutch painting; they seek to identify the ways in which images were used to shape contemporary views rather than simply ‘reflecting’ the social and physical environment. One of the most innovative and challenging approaches to the art of this period is to be found in Svetlana Alpers’s controversial book The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, in which she seeks to identify a distinctive northern tradition of ‘descriptive’ art that can be distinguished from the predominantly ‘narrative’ art of Renaissance Italy (Alpers, 1983, pp. xx–xxii). Characterising ‘iconicity’ as a ‘pervasive and limiting assumption of the study of art history’, Alpers contends that the search for meanings hidden beneath the surface of Dutch paintings led art historians to overlook ‘the pictorial mode itself – the reality effect – so basic to these pictures’ (Alpers, 1997, p. 57).

By locating what she terms the ‘visual culture’ of the Netherlands in the context of the growth of scientific knowledge and the development of new experimental technology, Alpers explores the idea that the ‘descriptive’ character of Dutch painting is closely tied to the ‘advancement of learning’ and the authority invested in visual as opposed to textual forms of knowledge. Just as technological innovations such as the microscope and the telescope, along with developments in cartography, helped to extend vsual knowledge of the world, painting also functioned as an ‘intermediary’ through which nature could be represented. On this sophisticated account, a concern with the ‘truth’ of images need not commit us to a naive form of realism, for pictorial depiction is identified as just one among many means of ‘representing’ the visual world.

Here we can take as an example Alpers’s analysis of the relationship between pictures and maps, which she investigates under the common heading of ‘the mapping impulse in Dutch art’. She notes that ‘In the study of images, we are used to treating maps as one kind of thing, and pictures as something else.’ (Alpers, 1997, p. 124) ‘ However, in some of Vermeer’s best-known paintings, including Young Woman with a Water Jug (Figure 29) and The Art of Painting (Figure 30), a map is included as a wall-hanging, creating a complex, nested relation between the painted surface and the depicted content. The inclusion of two different modes of representation within one and the same image draws attention to the artifice of depiction while at the same time blurring the boundaries between the pictorial and the cartographic. For Alpers, both are ‘forms of description’ that are ‘engaged in gaining knowledge of the world’ (Alpers, 1997, p. 57). Her aim is not to erase the difference between artworks and forms of representation that are normally categorised as ‘scientific’ but to show that both are rooted in a common endeavour of empirically based visual enquiry.

Alpers places great emphasis on the fact that whereas academic art practice, with its roots in the art of the Italian Renaissance, relied heavily on classical and biblical texts and, in turn, generated a large body of textual commentary and theory, the northern tradition of ‘descriptive’ art did not generate a comparable written discourse. Moreover, since most artworks were produced for the market rather than commissioned, we cannot look to contracts between artists and patrons as a source of information. Alpers uses this to support her claim that Dutch culture was predominantly visual rather than textual. However, the absence of documentary information telling us how works of art were interpreted and understood by contemporary viewers cuts both ways, since it means that there is a lack of reliable evidence to confirm or disconfirm the various competing strategies for explaining seventeenth-century Dutch painting.

8.1 The artifice of verisimilitude

The theoretical treatises on art that were published in the Netherlands do little to clarify the situation, since they tended to be written by authors who were indebted to academic and Italian art theory. For this reason, considerable significance has been accorded to a text by the painter Philips Angels (1616–83) that was originally presented as a lecture to the painters’ guild of Leiden in 1641 and was published the following year under the title Lof der schilder-konst (Praise of Painting). Angels seeks to entertain and, perhaps, to flatter his audience of fellow artists by extolling the virtues of painting and demonstrating its advantages over other art forms such as poetry and sculpture. As Eric J. Sluijter has pointed out, Angels’s arguments for the pre-eminence of painting are based not on the assertion that it can fulfil especially elevated or didactic aims – whether it be the encoding of hidden moral meanings or the pursuit of visual knowledge – but rather on its ability to imitate everything that is visible in nature (Sluijter, 1988, pp. 80–1). In order to establish the superiority of painting over sculpture, Angels delights in enumerating the variety of phenomena, both tangible and intangible, that painting alone is able to imitate:

in addition to depicting every kind of creature like birds, fishes, worms, flies, spiders and caterpillars it can render every kind of metal and can distinguish between them, such as gold, silver, bronze, copper, pewter, lead and all the rest. It can be used to depict a rainbow, rain, thunder, lightning, clouds, vapor, light, reflections and more of such things.

Detailed attention to the accurate representation of the individuating shape and texture of objects is undoubtedly a characteristic feature of the work of Leiden artists, who acquired the title fijnschilders or ‘fine painters’. The highly finished paintings produced by the artist Gerrit Dou (1613–75), who is thought to have been among the audience for Angels’s lecture, were particularly highly sought after and commanded correspondingly high prices. His Cook at the Window of 1652 (Figure 31) is a virtuoso display of the artist’s ability to depict an astonishing range of textures and surfaces, including fabric, feathers, fur, scales, metal, cabbage leaves and human flesh, and the different ways in which these reflect or absorb the play of light. The treatment of individual objects can certainly be described as ‘realistic’. Nonetheless, Peter Hecht is surely right to observe that while this painting ‘no doubt contains all sorts of information relevant to the history of Dutch seventeenth-century culture … [it] does not portray anything like a real cook in the window of a contemporary kitchen’ (Hecht, 1992, p. 89). Once our attention is drawn to the ‘fantasized stone niche with its sculpted relief parallel to the picture plane’, and the way in which this directly comments on the rivalry between painting and sculpture, the artificiality of the composition immediately becomes apparent. Dou employs a similar framing device, which itself forms part of the picture, in other paintings such as The Grocer’s Shop (Figure 32).

These paintings make it clear that realistic effects can be combined with a high degree of artifice, allowing the viewer to delight in the verisimilitude or ‘true-seeming’ quality of the representation without confusing art and reality. Some scholars have even suggested that in light of the diversity of Dutch seventeenth-century painting, and the complex issues of meaning and interpretation that are raised by such seemingly straightforward depictions of middle-class domesticity and sociability, we should speak instead of the ‘manifoldness of realism’ (Smith, 2009, p. 79). It is open to question whether the idea of a plurality of realisms can be sustained, for this seems to undercut the very notion of realism itself, but it does point up the need to sustain a variety of interpretative strategies, no one of which can claim to offer a comprehensive account of Dutch pictorial culture.

Conclusion

In this free course, Dutch painting of the Golden Age, you have examined a range of different strategies for interpreting Dutch seventeenth-century painting: the ‘direct realist’ interpretation, defended by Hegel and Fromentin, which treats Dutch painting of this period as a documentary portrait of a people, its landscape and its customs; the ‘disguised symbolism’ interpretation, defended by de Jongh, which employs the iconographic method to identify a hidden didactic or moralising content; and the ‘art of describing’ interpretation, defended by Alpers, which identifies close connections between Dutch visual culture and scientific enquiry. Each of these approaches has its strengths and weaknesses, and no interpretative strategy has succeeded in establishing its pre-eminence over the others. The absence of consensus among art historians reveals the difficulty of attributing meanings to works of visual art and the extent to which one and the same artwork can sustain divergent interpretations. The debate surrounding Dutch seventeenth-century painting is, perhaps, unusual in having such clearly defined contours, but the issues addressed in this course have a wider relevance in so far as they encourage us to think about the complex task of establishing the meaning of a work of visual art and the variety of approaches that are available to us.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A226 Exploring art and visual culture.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Jason Gaiger.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Course image: Photo: © Wallace Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 1: Photo: Collection Rijksmuseum.

Figure 2: Photo: © Wallace Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 3: Photo: Musée du Louvre/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 4: Photo: Kunsthaus, Zurich/ Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 5: Photo: The National Gallery/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 6: Photo: Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis.

Figure 7: Photo: bpk/ Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders.

Figure 8: Photo: © 2010 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Figure 9: Photo: Alte Pinakothek/Giraudon/ The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 10: Photo: © 2010 The National Gallery/Scala, Florence.

Figure 11: Photo: © Private collection/Johnny Van Haeften Ltd, London/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 12: Photo: © 2010. The National Gallery/Scala, Florence.

Figure 13: Photo: © 2010 The National Gallery/Scala, Florence.

Figure 14: Photo: © 2010 The National Gallery/Scala, Florence.

Figure 15: Photo: Collection Rijksmuseum.

Figure 16: Photo: Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis.

Figure 18: Photo: bpk/Kupferstichkabinett, SMB/ Jörg P. Anders.

Figure 19: Photo: © Amsterdams Historisch Museum.

Figure 20: Photo: Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis.

Figure 21 : Photo: Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Figure 22: Photo: Collection Rijksmuseum.

Figure 23: Photo: © 2010. The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Figure 24: Photo: courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art.

Figure 25: Photo: © 2010 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Figure 26: Photo: bpk/ Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders.

Figure 27: Photo: bpk/ Gemäldegalerie, SMB/Jörg P. Anders.

Figure 28: Photo: Collection Rijksmuseum.

Figure 29: Photo: © 2010 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/ Scala, Florence.

Figure 30: Photo: © Kunsthistorisches Museum/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Figure 31: Photo:akg-images.

Figure 32: Photo: The Royal Collection © 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Text

Extracts from: Fromentin, E. (1948 [1876]) The Masters of Past Time: Dutch and Flemish Painting from Van Eyck to Rembrandt (trans. A. Boyle), London, Phaidon.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University