1.5 Organisational objectives

Objectives are those things the organisation wants to achieve, the ‘whats’ of the organisation. A typical top-level objective in a profit-oriented organisation might be to increase profit. In a producer cooperative a top-level objective might be to improve the standard of living among our members and their families. In a campaigning organisation with a ‘green’ outlook a high-level objective might be to encourage the public to reduce their dependence on the private motor car.

Activity 4

Think of a group of which you are a member; it could be any group such as a group where you work, your family or a club. Write down three to five high-level objectives you think such a group would have.

Discussion

For a family group, three high-level objectives might be:

- to provide financial security for each family member

- to provide an environment of peace and safety, away from the world at large

- to provide a sound educational and social upbringing for any children.

Notice that all the objectives mentioned so far contain verbs such as to improve, to encourage and to provide. This is because objectives imply that action is required in order to achieve a goal. A goal might be ‘a happy family life’, but the members will need to take action to provide the financial security, the peaceful, safe environment and the sound upbringing of any children. Goals mark the general outcome of some effort or express the desired state that you would like to achieve. In contrast, objectives are often required to be SMART:

- Specific: be precise about what you want to achieve.

- Measurable: quantify your objectives.

- Achievable: are you attempting too much?

- Realistic: do you have the resources to reach the objective?

- Timed: state when you will achieve the objective.

For example, an internet-based mail order company might instigate a project with an objective to reduce delivery costs by 12 per cent by the end of the current financial year.

Identifying objectives

As we have mentioned earlier, it is usually the function of the board of directors or a similar stakeholder grouping to determine what the high-level objectives should be. There are a number of techniques for achieving this, which we illustrate below. In practice, there is a balance to be struck in order to achieve a set of objectives. For example, how much should be done individually or collectively? There will also be a variety of factors affecting the dynamics of achieving a result such as the tendency to value consensus at the price of the quality of a decision or to make more extreme decisions as a group than as individuals working alone (see, for example, McShane and Von Glinow, 2004, pp. 307–9).

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is one of the most popular techniques for generating a large number of ideas for the solution to a problem. The technique, which originated in the advertising industry in the 1930s, has three phases. In the first phase, participants, ideally a close-knit group of five or six people working in a private area and without interruptions or interference, call out ideas (usually in response to a question that identifies the problem). A facilitator or compère, who encourages participation and discourages criticism at this stage, writes the ideas on a black-or whiteboard, on a flipchart, on notes stuck to a bulletin board, or any combination of these, where every participant can see them all. When the pace of the interaction among the participants begins to falter or when the participants agree to stop presenting ideas, the group can move to the second phase, where they discuss the products of the first phase and can reject (possibly with reference to the mission statement) or keep individual ideas. Those which are kept can then be criticised constructively and roughly ranked in order of importance, interest or feasibility. A suitable form of criticism is to ask whether an idea can be developed in some way to make it more usable. The process may be repeated, which may involve rejecting some of the ideas kept in the first round of this phase. In the final phase the participants seek consensus on a form of ranking and use this to develop a ranked set of objectives.

Part of the preparation for a brainstorming session is to have a clear definition of the problem you want to solve and, if possible, identify any criteria that have to be met. The facilitator can use that definition to keep the group focused, especially when a particular train of thought takes the group away from the problem.

It is possible to brainstorm by yourself. While you can generate lots of ideas, it is not the same as working in a group. Working in a group is useful when individuals reach their limit on an idea. Another member of the group, with a different background and experiences, will often pick up the idea and take it forward. You need to remember that brainstorming is a lateral thinking activity that encourages you into new ways of looking at the problem. You are trying to open up possibilities and challenge assumptions.

The leader of a brainstorming session should encourage all of the members of the group, especially the quieter ones, to contribute. By relaxing the normal rules of work, the group has freedom to explore those wild and wacky ideas as well as the solid and practical ones. You can have fun, but the creative atmosphere can be stifled when ideas are criticised.

One of the problems of brainstorming with a group of people in a room is not getting all the ideas down on paper. When a group is very lively there is a chance that one voice might not be heard. So, some organisations try electronic forms of brainstorming such as email. The facilitator begins the process by posing a question. Each participant is then able to record their ideas as soon as they occur, which can lead to a greater number of ideas in comparison with brainstorming with a group in a single location. There are also dedicated software applications that let all the participants share ideas anonymously, which is a benefit for those who may be reluctant to contribute in a group environment. In contrast, some participants may feel threatened by some of the statements generated through the anonymity of individual contributions. So, the participants’ contributions may need to be moderated to guard against flaming and any other overt attempts to gain undue power and influence over the group.

In a conventional face-to-face session where all the participants are in the same place for a finite period of time, other things can be used to stimulate the discussion. For example, experts from a completely different domain may be brought in to demonstrate their products or ways of working. Because of the dislocation in time and place, electronic brainstorming requires more coordination and needs some planning to introduce extra examples and activities. There are some tricks that work in either environment when the ideas generation gets stuck. For example, you can consider how to prevent something from happening and reverse the ideas – sometimes called negative brainstorming, which follows the maxim:

In every opportunity there is a threat. In every threat there is an opportunity.

Nominal group technique

Another technique for obtaining objectives is the nominal group technique, developed by Delbecq et al. (1986). Once the problem is defined, the members of the group independently and silently write down as many ideas as possible over a set period of time (typically an hour or so). Then the group comes together in order to discuss the ideas. As with brainstorming, criticism and debate are discouraged although members can ask for clarification of ideas. In the next stage, members record their votes on the ideas in order to achieve a rank ordering or rating. Thus it is similar to but not as freewheeling as brainstorming. Its higher degree of structure is thought to maintain a higher task orientation and reduce the potential for conflict in comparison with brainstorming. However, the reduced social interaction in a nominal group can be a problem when the members are expected to produce more creative ideas.

Affinity diagrams

Both brainstorming and the nominal group technique result in a ranked list of objectives. The group can then classify their organisational objectives using affinity diagrams – drawing connecting lines between different objectives that are related in some way. A thick line can be used to indicate a strong affinity, and a thin line a weaker affinity. This helps to group related objectives together. Once these affinities have been identified, objectives can be classified under descriptive headings. An example of headings under which objectives were classified by an organisation devoted to promoting quality assurance and management techniques is:

- to increase the effectiveness of the service provided

- to increase customer satisfaction

- to increase profitability

- to increase job satisfaction

- to build a strong, global organisation.

We are less interested in how these objectives are identified and codified within an organisation than in how these objectives, which describe what the organisation wants to do, are developed into proposals (and ultimately into project plans) which enable the organisation to achieve its objectives. From a quality point of view, we are also concerned with how the organisation and the people working within it can ensure their activities, including project activities, all work towards achieving their objectives.

Towards project proposals

Objectives are what the organisation wants to achieve. The effort required to do so occurs within some period of planning: this year, over the next five years, over the next decade.

Turning objectives, the whats of an organisation, into plans, which are the highest-level hows, is the next task. We all have objectives we want to achieve. Say, for example, that we want to eat. We might plan how to achieve this objective by preparing a meal at home or going to a restaurant. Even this simple example shows us something important: there is almost always more than one way to achieve an objective. When there is more than one way to achieve an objective and more than one person or group involved, some degree of disagreement or conflict may arise. Someone who likes home-cooked food may well want to prepare a meal at home, but another person who is tired of eating the same sorts of food so frequently may want to visit a restaurant that serves exotic cuisine. Even one person can feel ambivalent about how an objective is to be accomplished: a tired parent may welcome a trip to a restaurant as a break from cooking, but may also dread having to deal with their small children in a public setting. These disagreements, conflicts and ambivalences can adversely affect the outcome of any decision. In organisations, they can cause a programme or project to stray from the spirit of the objectives it was designed to achieve and thereby can seriously compromise the quality of the result.

The use of organised brainstorming and group planning, particularly if widely practised in an organisation at all levels, will generally have two beneficial effects: people will feel that their attempts to contribute are welcomed and treated seriously; a good chance therefore exists that they will feel a measure of support for the outcome. People will be clearer about what the desired outcome is and how individuals and groups should work towards achieving it. Both these factors are unquantifiable, but contribute to the achievement of quality.

Matrix diagrams

The brainstorming technique together with an organising principle can be used to achieve the next level of planning within an organisation. This may still be a rather high and strategic level of planning, but the techniques described here can be repeated at lower levels where more detailed work is done to develop programme and, finally, project plans.

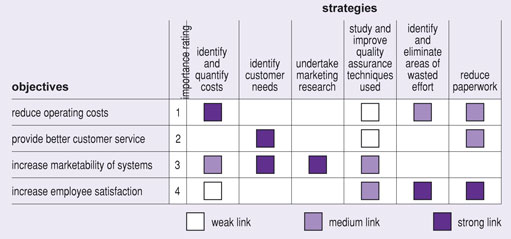

Identified objectives form the ‘what’ column in a matrix diagram, as shown in Figure 4. Scale ratings are given to indicate the importance of each objective based on an analysis of organisational requirements. A group (which may not be the same group that has identified the objectives) then brainstorms as described above, but the goal of this brainstorming session is to identify key strategies (‘hows’) to meet the already identified objectives. Strategies are then linked to objectives by placing them in the other dimension of the matrix diagram and indicating whether links are non-existent, weak, medium or strong.

Reiterating this process can be used to identify lower-level objectives and lower-level strategies and finally tactics. Taking Figure 4 as a brief example, in the next iteration the strategy of identifying and quantifying costs can become an objective, and a group can brainstorm or otherwise identify strategies for doing so: for example, looking at past invoices for certain items, identifying cheaper sources, identifying handling costs for those items and so on. You might ask customers to participate in this process, perhaps through market research or by direct participation in identifying and ranking objectives.

A project manager may have no input at all at the strategic level. However, as the key strategies are identified and increasingly refined through iteration, strategies can turn into programmes of change, and the tactics of realising those strategies can become projects. A project, to give yet another definition, becomes a way of employing a strategy or strategies to achieve an objective or objectives. This process – identifying objectives, refining and classifying them, rating them according to an agreed scale of importance, brainstorming key strategies and establishing the links between objectives and strategies – can also be used at the project level.

One clear advantage of carrying out planning in this top-down fashion is that it helps to keep people’s minds focused on the mission and key objectives of the organisation as they resolve strategies into finer and finer detail. Suggestions for changes from lower down in the organisational hierarchy can be evaluated by a similar method: how well does this suggestion fit with the organisation’s mission and objectives? This reduces the chances of creating projects that will not have, or may eventually lose, the support of higher management, or projects that diverge significantly from the main business of the organisation. Having a project mission statement and objectives that are clearly stated and understood by all the participants and management can be a major factor in the success of the project.

Example 4

A successful project to develop a system to check whether telephone bills had been paid and, if not, to remind customers by telephone is described in Norris et al. (1993). The authors note that having a strongly stated project objective prevented effort on this project from going astray. At one point the project team was tempted to apply a great deal of expensive and difficult technology to the problem. By going back to the project’s objective – to maximise the number of outstanding bills that get paid each month – the project team realised that the project was not about developing and implementing exciting new technology but about reminding people to pay bills. As a result, the final design was quite different from the initial thoughts of the project team. They avoided focusing on an isolated technical solution that was itself problematic and concentrated instead on the problem of reminding users who had not yet paid to do so. Norris et al. (p. 29) ask why the project went so well and answer their own question: ‘The main thing was kept the main thing. The project team never lost sight of their objective. They could easily have been seduced by ‘‘clever’’ solutions – the use of [automatic] message senders, smart software to detect answer phones, and so on. They continually asked the question, ‘‘Will this clear more unpaid accounts?’’’.

From objectives towards actions

We have not yet indicated where in this cycle objectives become actions and organisational plans turn into proposals for action. Drawing such a line is not so straightforward. However, as the process of identifying objectives and then determining the strategy or strategies to achieve those objectives continues, two things occur. One is that the ranking of objectives, combined with a notion of the strength of links between objectives and strategies, will gradually emerge as a set of priorities: objectives and strategies deemed the most effective to realise those objectives. As yet, no attempt has been made to determine the benefits of achieving a particular objective, nor whether a strategy is feasible and what it is likely to cost to effect that strategy. This is a necessary step before a project can be organised and authorised. It is a rare organisation that can afford to try all identified strategies to meet all of its objectives. That is why it is important to be able to rank objectives in importance and to identify those strategies which will be most effective at achieving the most important objectives.

The second thing that happens is that the proposals for action become increasingly detailed, and this enables a more accurate judgement to be made of their desirability, their likely costs and likely benefits. Different proposals compete against each other for organisational attention, and it becomes clearer as these become more detailed which are likely to be more do-able and of greater benefit.

The process of determining benefit increasingly is one of determining the value a proposal has for the organisation. This also provides a measure by which one proposal can be compared with another when choices must be made. However, value in this sense is not simply a matter of cost to build or cost to buy. It is a complex process, called the value process, of assessing each aspect of a proposal over its lifetime. At this early stage in planning, before any investment is made, the process is called value planning. Later you will meet some methods for assessing the financial costs and benefits of proposals. These form a part of value planning provided such aspects as an assessment of running costs (energy, maintenance, repair and replacement) and, ultimately, decommissioning costs are included.

Requirements

Generally speaking, a requirement identifies an expression of need, demand or obligation. An essential factor to ensure the quality of any project or any deliverable or product is to get the requirements for it right. If the requirements are not clearly and completely set out, any project or design based on them cannot succeed. Getting the requirements correctly defined during the initial phase of the project will minimise escalation of costs due to rework, client dissatisfaction and excessive changes during project execution and maintenance of the product afterwards.

Getting the requirements right involves the successful identification of:

- who is best placed to define the requirements

- what constitute acceptable and appropriate requirements

- what constitutes an acceptable demonstration that each element of those requirements has been achieved

- the resolution of technical, financial or organisational conflicts of interest that may appear in the requirements

- the agreement on and documentation of the requirements and demonstrations in the proposal.

Example 5

A large computer system often requires a data communications network. The network consists of a number of separate components. It is exceedingly complex and the suitability of particular components cannot be judged solely on simple criteria such as their cost. Instead, they have to be judged on a number of complex and interlinked criteria: compatibility with all the other components used on several levels ranging from the mechanical and electrical to the use of different protocols; capacity, dependability, ease of installation and size; the financial soundness and reputation of the manufacturer (can the manufacturer deliver the products wanted on time, and will the manufacturer still be in business when it becomes necessary to expand the network and more components are needed?); maintainability (ease and cost); ability to allow interconnection to other networks; running and purchase costs; and so on. All of these will have some bearing on whether component A is more suitable than components B, C or D, which may appear to do the same function and be cheaper to purchase. Making the correct choice is an important quality issue.

Requirements are a statement of the need that a project has to satisfy (APM, 2006). Each one identifies what is expected of a product or project. Drawing up the statement of requirements is one of the earliest steps in planning. A requirement is different from a specification in that the requirement is the starting point of a development and is an expression of those aspects which will define the thing to be done and the product to be developed. Requirements should not be confused with deliverables, which are the end products of a project as well as the measurable results of certain intermediate activities. A specification is a statement of the characteristics of a deliverable, such as its size or performance standards. A requirement might be ‘to be able to travel independently of the public transport system’. This could be met in a number of ways: by motor car, motor cycle or bicycle or on foot. A deliverable resulting from such a requirement would vary depending upon the stage of definition, but could be stated as: ‘a super-mini car’ or ‘an 1100 cc petrol-powered motor car capable of carrying four passengers’ or even one that specified in detail the length, width, height and colour.

It is only after much further work in feasibility studies and design, and often after prototypes have been built and tried, that a firm technical specification can be made.

A requirement must be appropriate and well defined. It is important to determine whether the proposed requirement is appropriate to real needs and expectations and to the value that the potential client will put on it. Then the client has to agree that the requirement is appropriate and meets his or her needs.

Even when a requirement is appropriate and well defined and everyone agrees on its meaning, if the parties have not agreed on how to demonstrate that a requirement has been met, the way is left open for the agreement concerning its meaning to break down over time. Setting out how it will be possible to demonstrate that a requirement has been met is therefore very important. This process is known as acceptance testing. The acceptance test criteria for each project deliverable need to be established at the same time as its specification. Desired characteristics are often set out in simple terms such as ‘easy to use’, ‘safe’, ‘reliable’ – but how will anyone know when ‘safe’ or ‘reliable’ have been achieved? It is best to avoid abstract or unquantified terms. One way is to state the required quality, say ‘easy to use’, and then list what factors contribute to this quality. For example, ‘easy to use’ can include:

- appropriate documentation written in plain English

- clues on the item itself which indicate how it should be used (for example, an item’s shape could mean it will only fit with another item in one obvious way)

- displays on the item directing clearly how it is to be used

- parts ergonomically designed for typical users, remembering that many people are not ‘typical’ (they may, for example, be colour-blind or left-handed or of above average height or users of a wheelchair).

This is not an exhaustive list of ways in which the quality ‘easy to use’ can be refined, but you should see how important it is to define a quality in a concrete and measurable way. It will be necessary to look at these specifics at a later stage and turn them into demonstrations. For example, the first item on our list above is ‘appropriate documentation’. Later on, we might want to specify that the demonstration of this is ‘the existence of a user’s manual which is complete, contains several useful and accurate worked examples and accurate and uncluttered illustrations’. Demonstrations must be testable, so they are expected to include components that are measurable. In the case of a new manual for a road de-icing project, we might include: ‘Operators shall be able to generate a de-icing schedule after one day’s training’.

This is a testable statement because it is straightforward to see whether or not the operators are indeed able to generate a schedule after just one day’s training (Robertson and Robertson, 2006).

Activity 5

Assume you are drawing up the requirements for a door. First, list two or three qualities that a door should exhibit, then refine these by listing two contributing factors for each quality.

Discussion

Three qualities that we could think of were: easy to use, draught-proof, attractive appearance. (You may have a different list.) The contributing factors we identified are shown in Table 3 (in some cases we have listed more than two).

| Quality | Contributing factors |

|---|---|

| Easy to use | Handle opens easily |

| Door swings or slides out of the way with minimal effort | |

| Door is wide enough to permit easy passage | |

| Draught-proof | Frame overlaps with door edges and fits well |

| Seals used to improve draught-proofing | |

| Attractive appearance | Smooth surface |

| Pleasing proportions | |

| Attractive hardware used |

We have not said anything about demonstrations here, but it would be possible at this early stage to set some additional qualities and contributing factors, such as extending the quality ‘easy to use’ by specifying that ‘the door must be usable by wheelchair users, people with Zimmer frames or pushchairs or with their arms full’. This would have a bearing on the door being wide enough, needing only minimal effort to open and close it, and the handle being easy to reach.

Requirements will affect the cost of any item and any project, and yet cost is only one criterion and may not be the most important. Other aspects may be vital to the success of the project.

Example 6

The design team for an early space satellite did not communicate to the purchasing manager the fact that all electronic parts needed to be ‘high reliability’ – able to perform after having been subjected to the pressures and vibrations of a launch, under conditions of near vacuum and alternating very low and very high temperatures. The purchasing manager proceeded to acquire electronic parts on the basis of price alone. High-reliability electronics are, of course, far more expensive than their ordinary counterparts. One of the key electronic components of the satellite failed to survive the launch because it was of the ordinary type.

Next step: feasibility

Once you have identified and ranked objectives and strategies at the organisational level and analysed major problems and their causes, made decisions about which to pursue further and set out your requirements and specifications, the next step is to identify those potential strategies which should be surveyed to see how feasible (how profitably do-able) they are. This stage is referred to as a feasibility study and places an emphasis on both technical and financial aspects. Feasibility studies may be undertaken for one or more potential strategies and the results of these studies may be used to decide which proposals to pursue.