3.3 Summary

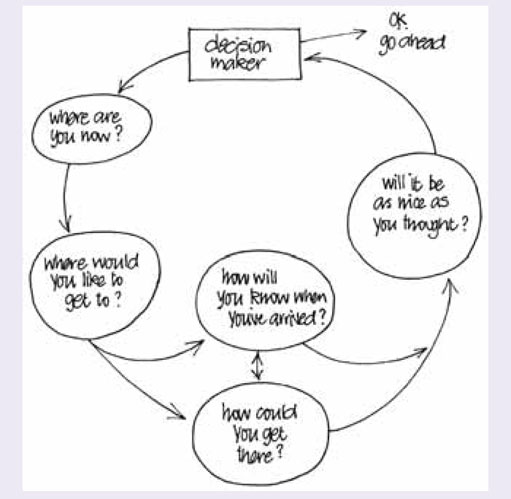

The creation of a project from organisational plans through proposals to decisions is often a protracted process which in itself calls for the use of special management skills and techniques. Certain questions need to be asked; these are shown in Figure 14 and they are phrased in everyday jargon-free language. The decision maker in the diagram is the person or people responsible for authorising a proposal.

If we define a project as the means whereby an existing state of affairs is transformed into a desired state of affairs, then before the project begins we have to be able to specify both the existing and the desired states. The difference between the two defines what needs to be done. Even in cases where the existing and desired states of affairs are the same, the organisation must be aware that the desired state can deteriorate in the future into something undesirable. In such a case the organisation needs to do something to prevent the future adverse state of affairs from arising. Of course the gap between an existing and a desired state of affairs is not necessarily sufficient stimulus to cause an organisation to embark upon a project: the organisation will pay attention to those problems and opportunities which the value system of that organisation suggests are important.

When proposals reach a stage where a decision is required it is important to base the decision on solid evidence and to avoid political expediency and the personal inclinations of the decision maker. A proposal needs to demonstrate an internal consistency: the parts need to fit together in a way which suggests that no part is grossly out of scale with the other parts. Decision trees can assist in guiding decisions, as can proposal-ranking formulas (when expenditure is estimated to be low), selection indexes, checklists and measured checklists. However, all these techniques require estimates of cash flows to be made for the economic life of a project: something that may not be feasible at the time the decision whether to proceed is required. Sometimes it is necessary to accept that a decision can be based on incomplete information. If that is the case, then it is important to keep other options open.

Having studied this section, you should be able to:

- describe an appropriate model for deciding which proposal to pursue

- explain why it is necessary to calculate profitability in the same way for proposals which are being compared in order to choose from them

- calculate expected monetary value (EMV) for possible outcomes in a decision tree

- explain how proposal-ranking formulas work

- use a checklist or measured checklist

- state the main limitation of these techniques

- list some of the questions a decision maker needs to ask before making a decision.