4.1 Project life cycles

Buchanan and Boddy said that a project is: ‘a unique venture with a beginning and an end’ (1992, p. 8). The bit in the middle is where most of the work is done. We say that a project has a life cycle, based on an analogy with living things which are born, grow, live for a period of time doing things such as consuming food and water, breathing, moving, and then finally end (death). The concept of a birthday is readily associated with the formal approval of a project, which is often associated with a contract between the client and the supplier. A fuller analogy with living things, like humans, involves a project’s conception and the gestation period before it is born. Different kinds of animal have variations in their particular life cycles and, just like projects, every living thing is unique in some sense or other.

There is much discussion about whether there is only one ‘true’ model of a project life cycle or many, and whether any of these are reasonably accurate descriptions of what happens in real life. Some writers include the feasibility study as part of the project life cycle; others believe that the project proper only begins once the feasibility study is completed and the proposal accepted, or only when cost codes and a budget for the project are defined by the company accountants. We will use the point of conception, even though the actual circumstances can make that gestation period rather cloudy or uncertain. The practical starting point is often considered to be the birthday, since management normally give approval after they have been presented with the feasibility study and decided to go ahead with further work. If you find it helpful, you can think of the work needed to carry out a feasibility study as being a mini-project in its own right.

Even with the best of plans and most stringent of controls, real life is always more chaotic than the models we apply to it; the same is true of projects. Nevertheless, in the case of projects, models are useful to help us recognise different ways of moving from the project’s beginning to its end, and the broad phases where the activities that take place change from one type to another. Each activity will be undertaken using a known procedure at a given level of formality, starting with a number of inputs from preceding activities that are the basis for further work. On completion of an activity there may be one or more outputs, which are known as deliverables (because they are needed for other activities). So, the order in which these activities are carried out is called a life cycle, which outlines the overall process for a given project. A phase is the term used to describe a set of interrelated activities that are needed to achieve a particular outcome or deliverable. When a life cycle includes a number of phases, it is usually because some form of evaluation or review is needed to decide when each phase is completed.

There is no single life cycle that applies to all projects, although certain types of project will be associated with a particular life cycle. We begin by describing a basic life cycle and then discuss some variations, which may provide an appropriate model for a given situation. We will use the characteristics of software to illustrate that a project’s outcome is more than just a physical object.

In practice, the description of a life cycle may be very general or very detailed: some might only suggest what to do, while others might prescribe what must be done. Highly detailed descriptions might involve numerous forms, models, checklists and so on which have been associated with the term project management methodology (see, for example, PMI, 2004).

The project life cycle

Many writers use four phases when considering life cycles in relation to project management. Turner, for example, used the life cycle of a plant as an analogy to that of a project (1999):

| Stage | Name of phase |

|---|---|

| Germination | Proposal and initiation |

| Growth | Design and appraisal |

| Maturity | Execution and control |

| Death | Finalisation and closeout |

Other writers, such as Weiss and Wysocki (1994), look at the core activities to come up with five phases such as define, plan, organise, execute and close. The change from one phase to the next is not necessarily abrupt. When there is significant overlap in time between activities in different phases (for example, when planning activities continue at the same time as the organisation is under way and execution may even have begun), we say that these activities exhibit concurrency. Since changes are an inevitable fact of project life, there will also be times when activities such as estimating or even recruiting or assigning work have to be done again in response to such changes. The overlapping of phases is also called fast tracking (PMI, 2004) as it allows the project to be completed in less time than following a strict sequence of phases.

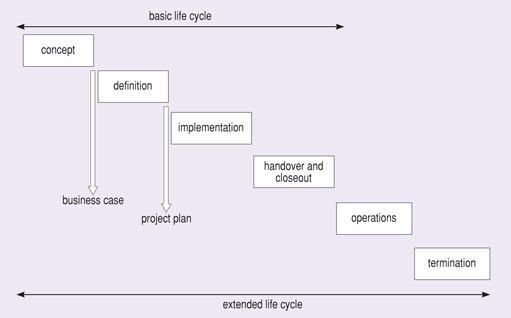

The basic life cycle, which will fit many projects, is shown in Figure 15.

The generic sequence of phases in the basic life cycle involves (APM, 2006):

| Concept | The need, problem or opportunity is established for the proposed project. Proposals are prepared and then tested for feasibility. Sufficient plans are made to enable a ‘go/no-go’ decision to be made, often in the form of a business case that is owned by the sponsor. The decision forms the end of the stage. |

| Definition | Some plans and general costs, of course, will have emerged from the previous phase, but more refinement will need to be done in this phase to create a plan that can be used by the project manager. During the iterative evaluation and optimisation of the preferred solution, the project’s scope, time, cost and quality objectives can be affected as the requirements are elaborated in greater detail. |

| Implementation (also known as execution) | The project management plan is put into action. The design of the project deliverables is finalised so that each one may be built. The important activities are: communication with stakeholders, monitoring costs, controlling quality and identifying and managing changes. This is the busiest phase of just about every project that uses the basic life cycle. |

| Handover and closeout | The final project deliverables are handed over to the sponsor. For example, the new facility is installed on the customer’s premises. Once the deliverables have been formally accepted, the responsibility and ownership shift from the project team to the sponsor or users. At this point, the project can be reviewed in order that lessons may be learnt from the stakeholders’ experiences. |

The extended life cycle, which is also known as a product life cycle, also shown in Figure 15 involves supporting and maintaining the deliverables in order to realise the project’s intended benefits. The extended life cycle adds two more phases to the sequence (APM, 2006):

| Operations | The period during which the completed deliverable is used and maintained in service for its intended purpose. |

| Termination | The disposal of the project deliverables at the end of their life. |

Projects related to special events, such as an annual conference or a sporting event, make use of the extended life cycle.

Deliverables have life cycles too

Each of the project’s deliverables, whether it is one that is handed over to the client or one that is produced from one of the intermediate activities, has a life cycle. Such deliverables tend to follow a product life cycle, which is much broader in terms of its general scope than the basic life cycle for a project (Dawson, 2000):

| Analysis | The initial investigative work done for the product – its idea, feasibility, definition and planning. |

| Synthesis | The work done to develop (and test) the product. |

| Operation | The implementation, use and maintenance of the product. |

| Retirement | The final withdrawal and replacement of the product. |

In general, these four stages are not mutually exclusive and there are common activities that lead to overlaps between stages. For example, a manufacturing organisation might initiate a project to develop and install a new production line. A phased implementation of the new equipment would lead to an overlap of the operation and retirement stages: between the reduced operation of the current production line and the pilot operation of the new one.

In addition, there will be a substantial amount of variation in the product life cycle because of the huge variety in the deliverables needed for projects in the real world. At the time of writing, for example, a new building is being constructed at The Open University for members of the Computing Department and the Institute of Educational Technology. At the same time, there are a number of software applications being developed to support students’ learning online. While there may be similarities between the life cycles involved, the actual processes used in construction and software projects have very little in common.

Space does not permit a detailed discussion of the processes used to produce the huge variety of deliverables. However, Section 6 contains a discussion of the different approaches used in software development, which may be used to compare the life cycles and processes used in other industries or problem domains.

Reviews and learning from your experiences

Reviews are a means to assess or make a survey of something. They give you a chance to reflect on what you have just done or produced (such as an assignment). For example, reviews are for testing whether or not the objectives specified in the project plan have been achieved, as well as assessing the achievement of the benefits identified in the business case. The effectiveness and efficiency of a review are improved by having a single focal point. A gate review, for instance, is a formal point in a life cycle where a decision is made whether to continue with the next phase of the project (APM, 2006). Figure 15 indicates that the business case will be the first, formal deliverable to be given a gate review.

Reflecting on your experiences is an important step in learning, which is exemplified in Kolb’s learning cycle (1984):

- concrete experiences, followed by

- observation and reflection, leading to

- formation of abstract concepts and generalisations, leading to

- testing of the implications of concepts for future action, which then lead to new concrete experiences.

The learning cycle refers to the process whereby you step back from an activity and review what has been done and experienced. After interpreting the events that have been observed, and making some sense of the relationships among them, you take the opportunity to refine how the original activity might be performed better in the future. In general, the learning cycle implies that making lots of small, incremental improvements may turn into major improvements over time. As a student, for example, you might engage in the learning cycle after each day’s work. Just one thing done differently next time could lead up to 365 improvements over a year!

In Kolb’s model, it is assumed that learning takes place when you pursue goals that are appropriate to your needs. So, you should look for experiences and interpret them in the light of those goals. It follows that learning becomes erratic when the goals are not clear. As a result of different behaviour patterns and work experiences, individuals will make different assumptions about what they see and understand through their experiences.

An activity or set of activities, like reviewing the business case, is a potential turning point for the work leading up to the final product. The internal relationships between different stakeholders may lead to misinterpretations of and misattributions to the meanings of the document. The potential consequences are confusion and frustration, which will not make for a healthy project. So, taking stock of the business case is an early chance to assess what might happen in the project as a whole, as well as getting the stakeholders to reflect on their experiences of the conceptualisation of a project.

Project classification

When making a case for a new project, part of the work includes the choice of life cycle to use in order to achieve its goal and objectives. If an organisation has been using projects for some time, it is likely that it has developed a particular life cycle for the kinds of project that are approved. The simplest way to classify projects is by industry: for example, construction, mechanical engineering, software development, banking or health care.

At the same time, it is also possible to think of projects in terms of their outcomes, which might be some form of product or service. However, the outcome of many projects has been a combination of products and services. For example, the National Health Service in the UK has sponsored a project for a new service that allows general practitioners to make hospital appointments for their patients in real time (service). In order to achieve the project’s objectives, a new software application (product) was developed. Hence, we might consider that one way to classify a project is according to the particular result or outcome that we want to achieve. In addition, it is also reasonable to include a consideration of the means by which the desired outcome is to be achieved. By combining a consideration of means and ends (answering the how? and the what? questions) for a project, there would be four classes of project according to how much is known about what you are trying to achieve and how you are going to achieve it.

In practice, the two extremes permit a simple qualitative assignment of a project into one of four classes. The use of a metaphor for each class of project helps stakeholders engage in it, which Obeng (2003) employs as follows:

| Type of project | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Painting by numbers | Most stakeholders are sure of what to do and how it is to be done. The project proceeds linearly and sequentially. | Housing construction by a well-established building firm |

| Going on a quest | Most stakeholders are sure of what to do, but are rather unsure about how to achieve it. The project proceeds concurrently and converges according to particular deadlines. | Outcome based on prototypes (like research and development) |

| Making a movie | Most stakeholders are very sure of how to do the work, but not so sure about what is to be done. The project proceeds through a number of checkpoints where clarification is sought before moving on. | Developing new products for the market |

| Walking (or lost) in the fog | Most stakeholders are unsure of both what is to be done and how it is to be carried out. The project proceeds with care, ‘one step at a time’. | Doing something new for the first time such as a quality or process improvement programme |

As you will see in Section 4.2, such a means of project classification is associated with the two main perspectives that are used to evaluate whether or not a project is successful.