2.2 The problem with problems

According to Wong (2020), a wicked problem is ‘a social or cultural problem that’s difficult or impossible to solve – normally because of its complex and interconnected nature’. Examples include poverty, global warming, and traffic jams.

Wicked problems can be complex and difficult to identify what the actual issue is, and what might be the best solution. This is often due to conflicting information and views, the interdependencies that need to be considered, the large numbers of people they might affect and their economic viability.

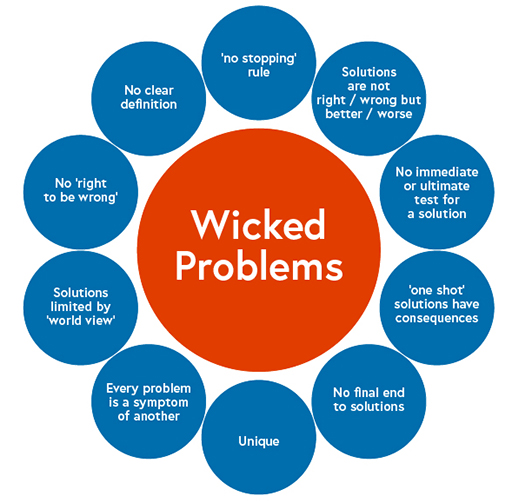

Rittel and Webber (1973) identified ten characteristics of wicked problems:

- There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem.

- Wicked problems have no ‘stopping rule’ (i.e., no definitive solution).

- Solutions to wicked problems are not true or false, but good or bad.

- There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

- Every (attempted) solution to a wicked problem is a ‘one-shot operation’; the results cannot be readily undone, and there is no opportunity to learn by trial and error.

- Wicked problems do not have an enumerable (or an exhaustively describable) set of potential solutions, nor is there a well-described set of permissible operations that may be incorporated into the plan.

- Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

- Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

- The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways.

- The planner has no ‘right to be wrong’ (i.e., there is no public tolerance of experiments that fail).

By its very nature, you may not be able to solve the overall wicked problem, but you can mitigate some of the consequences. This requires being open to ideas and experimenting with different approaches, such as human-centred design or an interdisciplinary focus (IDEO, 2022).

While wicked problems have a framework from which to consider then, another approach is to think about problems as ‘intractable’ − those for which there is no obvious approach to solving them. As you consider a problem you reframe it and try to make sense of the problem and look for different paths that will help to mitigate the issue. This draws from taking a more human-centred approach to problem solving.

Human-centred design is a creative approach to problem solving that starts with the needs of the user, emphasises the importance of diverse perspectives, and encourages solution-seeking among multiple actors. It consists of five phases: Empathise, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test. What differentiates human-centred design from other problem-solving approaches is its focus on understanding the perspective of the person who experiences a problem most acutely.

This involves observing, using empathy to explore the problem further, to uncover what at first might not be obvious, generating ideas, with test-and-learn activities to gather feedback, prior to implementing a potential solution.

Activity 3: What problems does your HEI have?

Read the following article: Nothing is intractable: you can change the world [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] and then consider if your HEI has wicked or intractable problems. And approaches that could be taken to understand them and potentially reframe or solve them.

Note your findings in the text box below.