8.2 Degrees of innovation

In terms of economic and social consequences, every innovation is not equal. Some innovations have far-reaching, even world-changing, consequences. For example, innovations like flaking flint to make knives and axes, double entry book-keeping, heavier-than-air flight and the World Wide Web have all been associated with deep changes to the way we live. Most innovations, however, are more modest and represent largely incremental improvements to existing ways of doing things. Some inventions remain unexploited, never to become innovations.

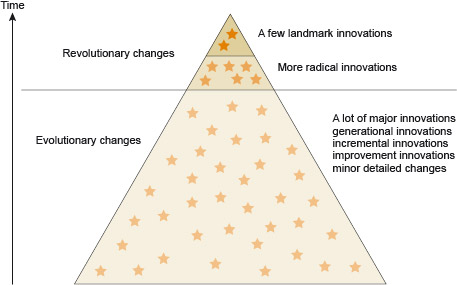

The terms used to describe different types or degrees of innovation are somewhat imprecise. One widespread distinction in the literature is between ‘landmark’ or ‘radical’ innovations with far-reaching consequences on the one hand, and the more typical ‘incremental’ innovations (see Figure 8). Landmark innovations are very few and rare. For example, it has been argued that the discovery of the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin in 1939 and 1940, respectively, represented the landmark innovation of the domestication of micro-organisms and is as significant as the domestication of wild animals (Kingston, 2000). (We might argue, though, that the domestication of micro-organisms took place rather longer ago than this, as for example in alcoholic fermentation, cultures for yogurt and yeast in bread.)