8.6 Product and process innovation

When we think of innovation, we frequently tend to think of innovation in products. However, as we briefly outlined in Sections 1 and 2, innovation in the processes by which these products are made and distributed can be as important, or even more important, in generating value. Changes in production processes can disrupt entire industries, as evidenced with float glass. To introduce the process, watch the following extract from the BBC programme Made in Britain [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

In the decades before 1960, there were two methods for making sheets of glass industrially. Sheet glass was made by pulling a ribbon of glass upwards using asbestos rollers, through a block floating on molten glass. As the glass cooled and hardened it was cut into sheets as required. This method was cheap but the glass was prone to flaws and optical distortion. Where higher quality glass was needed, for example in large shop windows or in mirrors, glass was rolled into a plate and ground and polished to produce a smooth surface, making plate glass. Plate glass was high quality but expensive to make. The two types of glass effectively comprised two separate industries, with different production plants and different customers. In 1953 Sir Alastair Pilkington, working in research and development at Pilkington Glass in Doncaster, UK, filed a provisional British patent for a new process, which became known as ‘float glass’. Here, molten glass is floated on molten tin, producing very even and flat sheets. With subsequent development it became possible to produce glass of the quality achieved by plate glass but without the capital and labour costs associated with grinding and polishing, and Pilkington Glass, one of the major international glass manufacturers, replaced their plate glass process with float glass processes in 1959.

During the 1960s the process was further developed and refined by Pilkington and others, allowing the faster production of thinner sheets of glass to the point where it was becoming competitive not just with plate glass on quality, but also with sheet glass on price. In Western Europe and North America, float glass replaced both of the earlier ‘industries’ by the mid-1970s with a method that produced high-quality glass at low cost. Glass production had been hugely changed by the emergence not of a new product, but of a new process for making the product (Uusitalo and Mikkola, 2010).

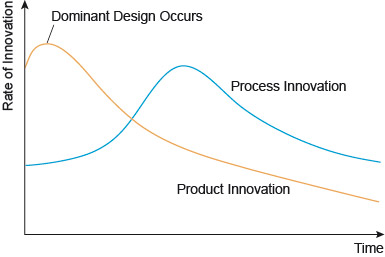

Glass manufacture is not an isolated example of this kind of innovation. Indeed, there is a recurring pattern: after a new product is introduced to the market, there is often a flurry of associated product innovation. As a dominant product design is established, however, product innovation often diminishes as a source of value. Instead, we may see an increase in innovative activity that reduces cost or adds value in the production process (Abernathy and Utterback, 1978) as illustrated in Figure 9.