8.9 Adopter categorisation

Typically, there is a small number of early adopters, and an even smaller number of what Rogers terms ‘innovators’, who are the first to adopt. (We should note that Rogers’ use of the term ‘innovator’ here to describe very earliest adopters of a technology is different from the way it is usually used to describe those who bring an innovation to market.) The experiences of these earliest adopters, and their connections to a wider population may influence the speed at which (or indeed, whether) others in a population adopt. Finally, Rogers identifies as ‘laggards’ those who adopt only after the vast majority of a population.

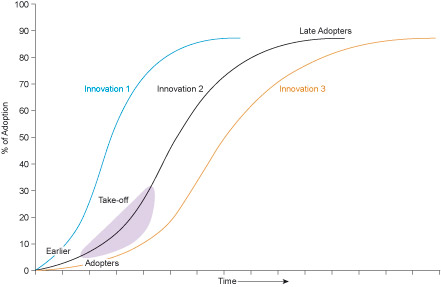

This pattern leads to an ‘S-curve’ of the spread of an innovation through a population (see Figure 12). The precise shape of the curve varies depending on the factors outlined above. Some innovations will inevitably diffuse more quickly than others. Others have elaborated on this, for example in the case of interactive media (Markus, 1987), where the usefulness of a telephone, email or, more recently, SMS (and software such as Skype, Facebook or Twitter) becomes increasingly useful as more people use it. This is unlike most technologies where the early adopter gains competitive advantage. These technologies, Markus argues, will either diffuse very rapidly or, if they fail to achieve some ‘critical mass’ of users, fall into disuse entirely.

Some have argued that Rogers’ view of the diffusion of innovation risks over-simplifying the process, reducing it to rather simple decisions of whether or not to adopt a given innovation. Rogers, they argue, views the innovation itself as relatively unchanging as it diffuses, though in later editions of his Diffusion of Innovations he briefly discusses the idea of ‘re-invention’ by users. However, in some contexts at least, particularly where organisations rather than individual consumers adopt innovations, the adoption decision and its associated implementation processes can be rather more complex.

For example, ‘configurational’ technologies are those, like factory robotic systems, that are not bought ‘off the shelf’ as a standard, well-defined product but where the implementation itself might be rather messy, requiring reconfiguration and the assembly of components in new ways. Here, innovation is not restricted to the design and building phase of a technology, but happens when the technology is being installed and used in a combined process which Fleck (1994) has called ‘innofusion’. Increasingly, there is interest in designing innovations precisely so that users can adapt them for use in new ways, which may then be taken up by someone else.