3 Operational risk

3.1 The implications of operational risk

As described above, operational risk – often shortened to ‘op. risk’ by practitioners – is a major type of non-financial risk that almost every organisation should consider and manage. In fact, for many smaller organisations with less formal risk management systems it might be the only non-financial risk taken into account. In these cases it is often defined quite broadly to encompass all the other non-financial risks.

The term ‘operational risk’ extends to the breakdown of controls and procedures within organisations – in effect, the processes intended to avoid the adverse consequences of all those other risks we have looked at in this free course. As we will discuss, carefully considered management controls must be applied by organisations to manage financial and non-financial risks, such as those arising from interest-rate and foreign-exchange changes and credit risk, that comprise the core of the content here. If, however, these controls are not observed – either deliberately through fraudulent activity or simply as a result of incompetence – then an organisation is potentially exposed to financial risks for which it has either no capacity or appetite.

As described in Boxes 8 and 9, the Sainsbury and Lufthansa examples both demonstrate that op. risk can have major adverse financial consequences.

Box 8 Sainsbury’s puts the brakes on IT after £290 million write-off

The United Kingdom supermarket Sainsbury’s revealed in 2004 that it had to take a £290 million loss. This arose when its disastrous IT project for its automated depots and supply chain failed to get goods onto the shelves of its supermarkets.

The extent of the problems, which arose from a £3 billion project, were revealed in Sainsbury’s new business plan put before investors in October 2004.

The write-off of redundant IT assets cost £140 million and the write-off of automated equipment in the new fulfilment depots cost £120 million. Another £30 million in stock losses arose due to the disruption caused by the new depots and IT systems. Remedial and completion capital spend on IT systems and the supply chain was estimated at an additional £200 million.

Sainsbury’s CEO Justin King said the business-transformation project distracted the company from its ‘customer offer’ and so he laid out plans to ‘fix the basics’ as part of a £2.5 billion ‘sales-led’ recovery for the embattled supermarket chain.

Sainsbury’s focus was now to be on getting cost savings by simplifying existing IT systems and, in some areas, this meant reintroducing manual processes where systems were failing.

Arguably, the cost to Sainsbury’s of the IT failures outlined in Box 8 was more than the financial write-offs detailed. The retailer’s competitors, particularly Tesco, were not standing still during this period of Sainsbury’s difficulties. Unsurprisingly, therefore, this period of operational difficulties saw Sainsbury’s lose market share to its rivals – and also saw a radical shake-up in the management of the company.

Box 9 Lufthansa cancels flights after computer failure

Lufthansa had to cancel about sixty European flights and its services around the world were delayed following a computer fault in its check-in system on 24 September 2004.

The company’s Star Alliance partners (Britain’s bmi, Poland’s LOT and Austrian Airlines) were also affected by the problem.

The flight cancellations affected about 6,000 passengers, while short-haul and long-haul departures were delayed by up to two hours. Some freight normally carried by plane had to be moved by truck.

At Berlin’s Tegel airport there were long queues as clerks had to write tickets by hand and tell passengers there was no assigned seating.

A Lufthansa clerk said the problem was not caused by a virus, but by the launch of a new computer program overnight, which brought the system down.

Unisys said it deeply regretted the failure of its check-in system, which went down following a planned outage.

‘After being rebooted, the operating system and hardware ran smoothly for approximately ninety minutes until a software problem brought the check-in system application down,’ Unisys said.

The company had to install new software to fix it.

The financial markets reacted to this operational failure, with shares in Lufthansa falling 1.8% to 9.32 euros.

It is consequently no surprise, particularly in the financial services sector, that greater scrutiny is being given to the operational risk being run by organisations. Indeed, the collapse of Barings in 1995, and the high-profile losses arising at the Allied Irish Bank’s US subsidiary Allfirst in 2001, were both classic examples of the financial mayhem that can arise through the existence of inadequate operational controls or a breach of the pre-set control procedures. Let us look more closely at the Barings episode in Box 10.

Box 10 Barings – a very simple (but costly) operational failure

As related earlier in this free course, the United Kingdom merchant bank Barings collapsed in February 1995 as a result of losses amounting to nearly £800m arising from derivatives trading by its Singapore subsidiary.

Derivatives are financial instruments whose prices are dependent upon or derived from one or more underlying assets. Derivative transactions are contracts between two – and sometimes more – counterparts. The value of derivative contracts is determined by movements in the prices of underlying assets.

Much of the media coverage focused on the complex nature of derivatives trading – although in the case of Barings the transactions on which money was lost were mostly simple bets on equity prices that went wrong.

It was not, then, the arcane nature of derivatives that caused the collapse of Barings – rather the lack of some basic operational controls. With limited staffing in its Singapore subsidiary, Barings failed to ensure the effective segregation between its trading activities and the recording and accounting of those trades. One trader, Nick Leeson, executed the transactions, took it upon himself to record the financial outcomes of certain of these trades (in a secret account coded 88888) and also managed the movements of funds to support them. This enabled him to start concealing loss-making transactions and their financial consequences for the bank for several months.

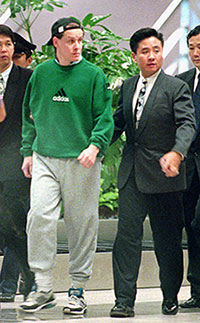

Eventually the adverse cash-flow consequences of the bets that had gone wrong had to surface as counterparties to the transactions sought their ‘winnings’. Barings collapsed at a spectacular speed and Nick Leeson, after fleeing, was apprehended at Frankfurt airport and returned to Singapore to serve time in prison for his fraudulent activities.

The collapse could so easily have been averted by applying a simple operational control. If Nick Leeson had not been able to record his own transactions and move funds to support his trading positions – that is, if the trading activities had been properly segregated from the settlements and accounting function in Singapore – then the loss-making trades would have been identified and reported by other staff at an early stage. This would have prevented the losses from escalating. Barings might have taken a financial loss as it unwound these trading positions, but it would have survived.

Ironically, the number eight is, according to the Chinese, supposed to bring luck. Clearly it failed to do so for Nick Leeson and Barings Bank!