1 Inner and outer contexts

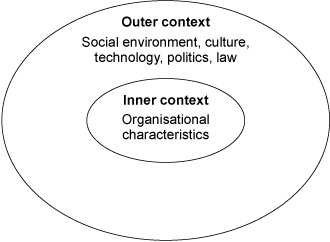

It has become an accepted convention to distinguish between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ contexts. The internal context essentially refers to the inner context, that is, the organisational environment within which HR management takes place. The external, or outer context refers to the environment outside the organisational boundaries. This latter includes societal characteristics, the prevailing culture (this could itself be multi-layered – for example local, regional and national culture), the technological environment and the political and the legal environment. These features are summarised in Figure 1.

Activity 1: Your organisational contexts

Populate the figure below with details of your own organisation’s inner and outer contexts, or use a case organisation with which you are familiar. Use the contexts already identified in the figure as a starting point for your ideas.

Click ‘View’ below the figure to access the note-making version of the figure.

Discussion

In this kind of introductory exercise, many people struggle to go beyond the abstract concepts for the outer context and they struggle to identify relevant inner context elements. The practical skill we are working towards is to identify factors most relevant to specific work organisations. This will also mean identifying and interpreting trends and other dynamic elements of contexts.

So, HR strategic choices take place in multiple contexts. The broad theory is that there is an interplay between economics, policy and institutions. For example, the impact of recession on societies of all kinds has been dramatic. Especially notable has been the increase in unemployment, particularly youth unemployment.

But the nature and extent of the impact is affected by the institutional arrangements and the policies followed – as well as the extent of debt. For example, Germany has maintained an apprenticeship system based on an investment in human capital approach. This has been underpinned by state policy and by regulation. Thus, the requirement to have a ‘license to practice’ in so many occupational areas means that employers need to invest in education and training in order to have access to such labour resources. The system becomes self-supporting because, as a consequence of the commitment to substantial training by employers, vocational and educational training is taken seriously by parents and young people – and so the quality is sustained. Without such a constellation of supporting structures of regulation, institutions and cultural esteem, numerous vocational educational and training initiatives in other countries, including the UK, have struggled to make a sufficient impact.

This example points, in a powerful way, to the critical importance of context. And yet it does not mean that context of one sort (here national differences) is entirely deterministic. There are, for example, exceptions even in the UK to the generally poor apprenticeship system – the case of Rolls Royce aerospace is one such exception. But that company’s effort in building and sustaining an effective apprenticeship system is unusual and exceptional; it is enabled by a powerful international brand.