1.1 Polar bears and pollutants

Attaching a satellite-tracking device to polar bears is not easy, and they have to be drugged (Figure 2). This gives an opportunity for them to be weighed, measured and tagged, and have various samples such as hair, fat and teeth removed for later chemical analysis.

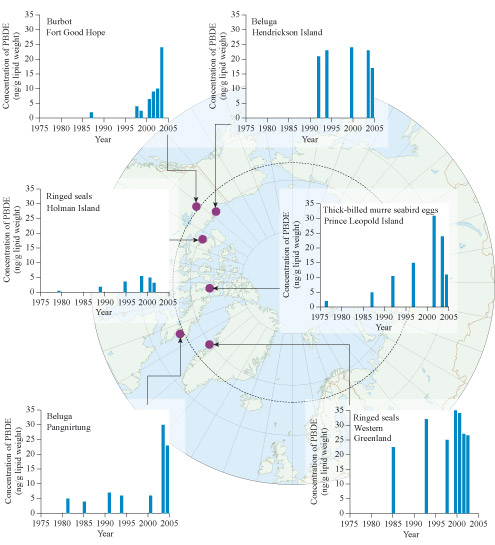

The amount of body fat on a bear indicates whether it has been eating well or is starving. But a chemical analysis of this body fat gives a surprise: polar bears have measurable amounts of a family of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in their fat. The same family has also been measured in Arctic ringed seals and other Arctic wildlife (Figure 3).

PBDEs are a group of synthetic chemicals developed over the 20th century as fire retardants. Fabrics and furniture are impregnated with them, with the sole aim of slowing the rate at which they burn, and for which they have been very successful. However, once created, PBDEs are very difficult to destroy and will not break down into their elements over time. For this reason they are considered a persistent organic pollutant (POP).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, scientists began to detect POPs in the tissues of fish and shellfish close to populated areas. Concentrations were then detected in human breast milk, and the levels were shown to be increasing with time – perhaps through direct exposure to PBDEs or through bioaccumulation (see Section 1.2). The scale in Figure 3 is given in nanograms per gram. So in every gram of the sample of beluga fat from Pangnirtung in 2004 there are about 30 nanograms of PBDE. This is 0.000 000 03 grams of PBDE in every gram of sample, or 0.03 parts per million (ppm). This may seem an extremely small amount, but PBDEs are potentially very toxic to liver and thyroid function, and have been shown to hinder development of nerve tissue in mammals. For this reason, the European Union banned several of them in 2004 and then more in 2008.

The migration of PBDEs into humans and shellfish can be explained by proximity to where they were used. While it is relatively simple to see how PBDEs can get into subjects close to their source, the PBDEs that end up in some of the wildlife in the Arctic have to be physically transported there. You will look at how pollutants are transported to the Arctic by flows around the Earth later in this course, but before you do, the following section looks at how pollutants can accumulate in the environment.