1.2 Globalisation is about networks

Globalisation is a term that refers to the flows around the world of species, money, goods, ideas, people, etc., and the networks that are integral to these flows. The word is used to attempt to capture a dizzying mix of recent economic, political and socio-cultural developments. The term can also be applied to ecological globalisation. The global transport of people, goods and services has massively increased. Technological and economic networks have developed to smooth trade and economic growth. Communications technologies have underpinned these networks.

You have already seen evidence (and there is more to come) that all networks have the inherent potential to be put to a vast range of uses. Even the internet, with its origins in ambitions for robust military research and development communications networks, can do as much to advance debate and action on sustainability as it can for the profit margins of immense global companies. Once the capacity for networks exists, they cannot easily be owned, directed, managed or, above all, predicted. This is what makes it impossible to capture what is going on in the world.

This section will emphasise that there is not one process called ‘globalisation’ but, rather, a collection of interwoven threads. Furthermore, the processes described are not something new and wholly unique to the present. This course focuses entirely on telling the story of human societies’ apparent responsibility for causing climate change – perhaps the most dramatic example of ecological globalisation there is. This section connects this to the social or cultural and political globalisation that is reflected in the new ways in which people are organising and making their voices heard and the new ways of making decisions beyond and within nation states.

Hence four threads can be identified from these varied uses of the term globalisation.

Economic The flows of money, goods and services around the world. In any hour of any day, you can be reminded of this by a glance at the labels on the products you use, or at news reports of a company shifting its plant from one part of the world to another (usually cheaper) location. Although the world has seen unprecedented wealth created via economic globalisation, it has also seen inequalities widen. Increasingly interdependent global economic structures present a huge challenge to attempts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Political The flow of ideas, ideologies and political systems. The process of globalisation has disseminated free market capitalist orthodoxy – generally allied to democratic systems of government – throughout the world. With these processes has come growth in the environmental and social movements. Conventions on climate change, biodiversity and trade agreements, shaped by, among others, global rather than national networks (patterns of interaction) of science, business and NGO interests, are tangible expressions of this political globalisation. Globalisation sees longer (and usually more complex) chains of cause and effect established. It is often pointed out that we don't have well-established institutions of global governance. They certainly can't yet claim to match the pace and extent of economic globalisation.

Social/cultural The flow of social practices and cultural products. This is often characterised as ‘McDonaldisation’ (Figure 1) – the relentless spread of western (especially American) culture. However, these flows also include counter-currents, such as the global fame or notoriety of the French anti-globalisation campaigner and farmer Joseph Bové, and the Indian author and environmentalist Arundhati Roy. Some authors argue that the emergent ‘global culture’ allows the development of a political and ethical underpinning for sustainable development, and that this will be accelerated by networks (see, for example, Urry, 1999).

Ecological Global movements of species, specifically in tandem with globalising human activities of development, trade and tourism. Publicity about global flows of pollutants in the 1960s and 1970s drove many people to support environmentalism. More recently, ozone depletion and climate change represent perhaps the most dramatic evidence of globalised and linked processes of environmental change.

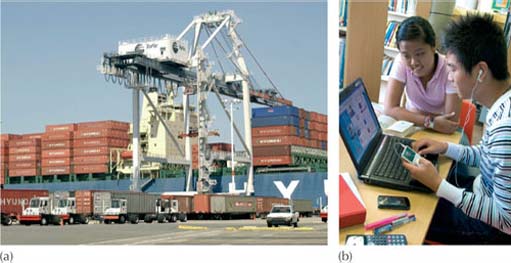

How have the inventions shown in Figure 2 assisted globalisation?

Goods containers helped to accelerate economic globalisation from the mid-1970s onwards, reducing costs and speeding up the haulage of goods (in turn, having huge environmental consequences in the form of increased road freight). Communications technologies have reduced or eliminated the constraints of time and space on human interactions, thus feeding cultural and political globalisation.

What is meant by the words ‘flow’ and ‘network’?

‘Flow’ is the movement of goods, people, cultural objects and ideas, or information across space and time. ‘Network’ in this context refers to patterns of interaction between independent people, places or institutions.