4.4.1 Partnerships for sustainable consumption

Moderate NGOs, progressive businesses and government all have a stake in seeing roundtable partnerships come up with practical steps that can bring sustainability closer. One area that has attracted the attention of all these players is consumption. Directing or limiting consumption is politically difficult for even the NGOs to promote. Similarly, ‘voluntary simplicity’ of the sort lived at Findhorn eco-village (Box 2) is not something that mainstream business will support. Hence sustainable consumption is an obvious goal around which these partners can gather. Two prominent examples are the Forest Stewardship Council or FSC (Box 4) and the Marine Stewardship Council or MSC, both examples of attempts to create sustainable supply chains of raw materials that are subject to intense and unsustainable exploitation.

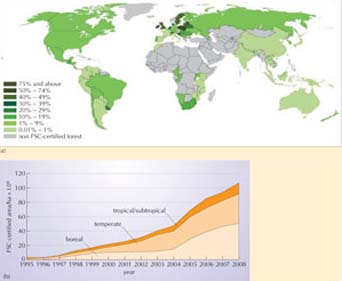

What might the geographical spread of FSC certification say about the governance of forestry? Contrast Europe with Africa.

Looking at Figure 18, there appear to be wide differences between European and African percentages of certified forestry. There could be a combination of factors:

European civil society and government are demanding sustainable forestry practices; management systems in the EU exist in an increasingly tight environmental regulation context;

governance of African forestry supply chains may make it more difficult to achieve certification;

some of the initial promoters of the FSC approach may be EU based.

Careful research would be required to know what precisely the reasons are, but the information in Figure 18 is a good starting point.

Box 4 Forest Stewardship Council – a partnership for the future of forests

The Forest Stewardship Council is an international non-profit organisation founded in 1993 to support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world's forests. With offices in Mexico and Germany, it is an association of members including environmental and social NGOs, the timber trade and the forestry profession, indigenous people's organisations, community forestry groups, and forest product certification organisations from around the world.

Forest certification is a way of assessing and certifying claims to have put sustainable forestry in place. Operations are assessed against a predetermined set of standards. The FSC's standards aim to establish a global baseline to aid the development of region-specific forest-management standards. Independent certification bodies, accredited by the FSC in the application of these standards, conduct impartial detailed assessments of forest operations at the request of landowners. If the forest operations are found to conform with FSC standards, a certificate is issued, enabling the landowner to bring product to market as ‘certified wood’, and to use the FSC trademark logo (Figure 17).

Chain of custody is the process by which the source of a timber product is verified. To carry the FSC trademark, a timber has to be independently tracked from the forest, through all the steps of the production process, until it reaches the end user. By mid-2002 there were more than 1500 FSC-endorsed Chain of Custody (COC) certificates in the world (Figure 18a). In the space of five years, there was a fivefold increase in the area of FSC forest (Figure 18b).

The FSC is a compelling and exciting case but it remains a rare one. For sustainability steps to be a convincing way forward, there need to be ways of scaling up the occasional success stories and to make them mainstream.

If you put together enlightened business, concerned and often organised civil society, and a communications system which the world has never seen before, you can expect some progress. However, it is widely believed that this progress will remain marginal, and unsustainability will continue as the norm unless government becomes involved and starts to give some regulatory shape to sustainability principles.

Activity 5 Which path to sustainability?

This activity invites you to assess the usefulness and viability of the three different approaches to achieving sustainability outlined in this section. To do this, ask yourself the following questions and make notes on your answers.

With which of the three approaches do you most identify?

Do the examples given in this section convince you that societies can adapt to environmental change and become sustainable?

Are they exclusive alternatives, or can they be combined?

Discussion

Here are some of the author's thoughts.

You might conclude ‘all of them and none’. Business can deliver creative solutions to problems, and a capitalist economic system can offer the means of replicating them quickly. But such best practice won't be universalised without external pressure from government and civil society. There is no evidence of widespread preparedness for a shift to ‘intentional communities’, or a locally based alternative to economic globalisation, but society at large can benefit from the hard thinking about what quality of life really means. Of course, stepwise progress towards sustainability appears to be the ‘reasonable middle ground’ but that is precisely its problem. It is just a little too well reasoned and sensible to grab people's attention at a time when they are trying to meet their immediate needs and wants.

Interface, the Findhorn Foundation and the Forest Stewardship Council are impressive and exciting. In different ways and for different audiences, they represent pathfinders for society, but they are very much exceptions.

Taken as a messy interconnected whole, the approaches begin to offer some sources of hope. However, it would be a mistake to hold your breath waiting for single answers to the issues of global environmental change to appear fully formed.