Intervention at Lake Taihu

Lake Taihu is an interesting example of a complex part-natural, part-human induced long-term environmental problem that has been approached using a wide range of interventions. It is one of China’s most notorious environmental disasters, which highlights the effects of political inertia and lack of administrative capacity.

In 2007, the choking of Lake Taihu, the country’s third largest freshwater lake, by a toxic algal bloom led to water supplies being contaminated for several days for over two million people (Figure 20). It sparked panic hoarding of bottled water as an alternative water supply and led China’s then premier, Wen Jiabao, to say: ‘The pollution of Taihu Lake has sounded the alarm for us.’ While he went on to call for cooperation between central and local governments, and for environmental workers and others to investigate the water crisis and devise a plan to tackle the contamination, the root of the problem was clear. The algae had flourished as a result of contaminants emitted from small factories and crab farms along the lake’s shore. However, there was little that the State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), the precursor to the Ministry of Environmental Protection, could do. As SEPA officials explained, they were in a bureaucratic stranglehold, as the crab farms fell under the Ministry of Agriculture, the wastewater treatment plants under local governments, and the lake itself under the Ministry of Water Resources (The Economist, 2008). This decentralisation of power is a legacy of Deng’s reforms of 1978. A lack of joined-up administration had resulted in environmental disaster.

This situation is a typical example of the consequences of failing to take a broad, systems approach to a situation where different stakeholders have different perspectives. The industrialists and the Ministry of Agriculture saw it as an economic system, providing a source of raw material and a sink for waste products. The Ministry of Water Resources and local consumers saw it as a water supply system, while environmental groups saw it as providing the habitat within which all had to live, providing ecological services such as water and clean air, and aesthetic outputs such as landscape and wildlife. For the industrial users, the presence of algae in the lake was not part of their system, and therefore did not matter. While water consumers and the relevant ministry were concerned about water quality, they had no means of controlling the activities of industrial users, and while environmental groups’ concerns may have embraced all these aspects, they had no direct means of controlling others’ activities.

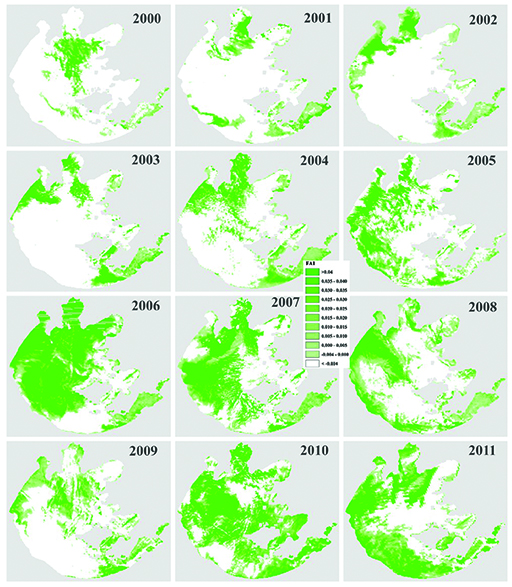

Duan et al. (2015) used satellite data to explore how different climate and catchment factors may have influenced the algal blooms over a 12-year period (2000–11). The results show annual variability in bloom coverage and an overall increased trend across the period (Figure 20).

Algal blooms are a ‘natural’ phenomenon. For example, El Niño affects patterns in wind and rain on Lake Taihu, and nutrients – when they become available in warm weather – can trigger algal growth. But the phenomenon can be seriously enhanced by industrial pollution and agricultural run-off. Despite sustained political attention, the problem of Lake Taihu’s algal blooms remains intractable and illustrates the difficulty of remediating challenging and compromised ecosystems.

In the wake of this and other disasters, the central government upgraded SEPA to a ministry in 2008 in the hope that the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) would enable it to combat political inertia and the lack of administrative capacity more effectively. A combination of the successive greening of the 11th, 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans together with the establishment of the MEP is beginning to have measurable effects on local and regional environmental management across a number of indicators such as air quality, water quality and carbon dioxide emissions. There is also some evidence of particular progress around ecological indicators relating to forests and ecosystems (Ouyang et al., 2016).

Committing sufficient funds to clean up and safeguard China’s environment is a further concern. In 2015, the then environment minister Chen Jining estimated that China would need to spend 8–10 trillion Chinese yuan renminbi (around 1.4 trillion US$) over the next few years to address the problems (Zhou, 2015). However, it remains to be seen whether this will be distributed to existing government agencies without a more widespread shake-up of processes and approaches, which means that the conflict of interest is likely to continue. Meanwhile faith has to be placed in the march of citizen-led concern for the environment both in China and elsewhere in the world.