5.2 Energy efficiency improvements

5.2.1 Supply-side measures

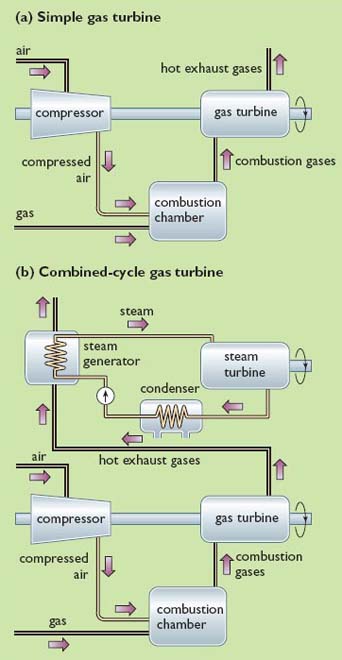

On the supply side of our energy systems, there is a very large potential for improving the efficiency of electricity generation by introducing new technologies that are more efficient than older power plant. The efficiency of a power plant is the percentage of the energy content of the fuel input that is converted into electricity output over a given time period. Since the early days of electricity production, power plant efficiency has been improving steadily. The most advanced form of fossil-fuelled power plant now available is the Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT).

CCGTs are more than 50 per cent efficient, compared with the older steam turbine power plant that is still in widespread use, where the efficiency is only about 30 per cent, and thus two-thirds of the energy content of the input fuel is wasted in the form of heat, usually dumped to the atmosphere via cooling towers.

CCGTs are more 'climate friendly' than older, coal-fired steam turbine plant, not only because they are more efficient but also because they burn natural gas, which on combustion emits about 40 per cent less CO2 than coal per unit of energy generated. Overall, taking into account both the higher efficiency and natural gas's lower CO2 emissions, when compared with traditional coal-fired plant CCGT-based power plants release about half as much CO2 per unit of electricity produced. Most of the reductions that occurred in Britain's CO2 emissions during the 1990s were due to the so-called 'dash for gas' as a substitute for coal in power generation.

In some countries, the 'waste' heat from power stations is widely used in district heating schemes to heat buildings. In 2000, some 72 per cent of Denmark's electricity was produced in such 'Combined Heat and Power' systems.

After fuels have been converted to electricity, whether in CCGTs or steam turbine-only plant, further losses occur in the wires of the transmission and distribution systems that convey the electricity to customers. In the UK, these amount to around 8 per cent. Overall, this means that even when a modern, high-efficiency CCGT is the electricity generator, less than half the energy in its input fuel emerges as electricity at the customers‗ sockets. In the case of older power stations the figure is around one-quarter.

Clearly, there is room for further improvements in the supply-side efficiency of our electricity systems, by further increasing the efficiency of generating plant and by ensuring that whatever 'waste' heat remains is piped to where it can be used.

Coal, oil and gas, when they are used directly rather than for electricity generation, are also subjected to processing, refining and cleaning before being distributed to customers. Some energy is also lost in their distribution, for example in the fuel used by road tankers or the electricity used to pump gas or oil through pipelines. However, these losses are much lower, typically less than 10 per cent overall. This means that over 90 per cent of the energy content of coal, oil and gas, if used directly, is available to customers at the end of the processing and distribution chain. The scope for further supply-side efficiency improvements is obviously much more limited here than in the case of electricity.