6.6.2 The World Energy Council scenarios

What are the possibilities for radical changes in our energy systems when viewed from a world perspective? There have been numerous studies of the various future options for the world's energy systems. One of the most recent and most comprehensive was produced in 1998 by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the World Energy Council (WEC), a version of which was published in 2000 as part of the United Nations' World Energy Assessment (United Nations Development Programme, 2000). IIASA is a leading 'think tank' based in Austria, whilst the WEC is a body that represents the world's main energy producers and utilities. For simplicity, we shall refer to their scenarios here as the World Energy Council (WEC) scenarios.

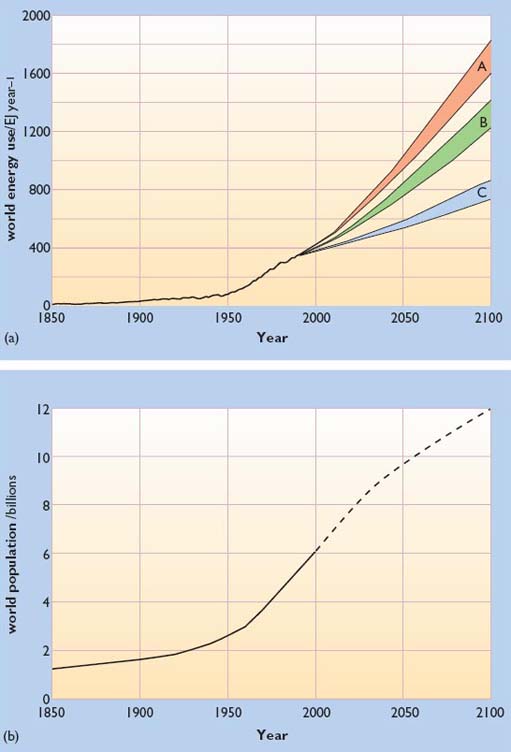

There are six WEC scenarios in all, and these have been grouped into three 'cases', A, B and C. Case B includes only one scenario, termed 'Middle Course'. Case A consists of three 'High Growth' scenarios, and case C includes two 'Ecologically Driven' scenarios.

Each scenario incorporates different assumptions about rates of economic growth and the distribution of that growth between rich and poor countries; about the choices that are made between different energy technologies and the rapidity with which they are developed; and regarding the extent to which ecological imperatives are given priority in coming decades. They all assume that world population will increase from its current (2000) level of around 6.1 billion to 10.1 billion by 2050 and 11.7 billion by 2100. (More recent UN projections, however, suggest that these figures may be over-estimates, with 9 billion as the new median population estimate for 2050 (United Nations, 2001). Other recent research also suggests that world population is likely to peak before the end of the twenty-first century and then begin to decline. (Lutz et al., 2001)).

The results of these assumptions are shown in Figure 56 which also shows world population growth from 1850 to 2000 alongside the various scenario projections to 2100.

In all three High Growth scenarios, the world's economy expands very rapidly, at an annual average rate of 2.5 per cent per annum – significantly faster than the historic growth rate of about 2 per cent per year. In all of them, primary energy intensity (the amount of primary energy required to produce a dollar's worth of output in the economy) reduces quite rapidly, reflecting a fairly strong commitment to energy efficiency measures and/or dematerialisation. The three scenarios differ mainly in their choices of energy supply technologies. One is based on ample supplies of oil and gas; another envisages a return to coal; and the third has an emphasis on non-fossil sources, mainly renewables with some nuclear. By 2100, the High Growth scenarios all envisage world primary energy consumption rising to 1859 exajoules, more than four times the 2000 level.

In the single Middle Course scenario, economic growth is lower than in the High Growth scenarios, averaging around 2.1 per cent per annum, close to the historic average rate. Primary energy intensity improves rather more slowly, reflecting a slightly lower world-wide emphasis on energy efficiency improvement. Energy supplies come from a wide variety of fossil, nuclear and renewable sources, and by 2100 total primary energy consumption has reached 1464 EJ, over three times the 2000 level.

In the two Ecologically Driven scenarios, world economic growth is 2.2 per cent per annum, slightly higher than in Middle Course, but there is a very high emphasis on improving energy efficiency, reflected in substantially lower primary energy intensity figures. Both scenarios feature a strong development of renewables, alongside a continued use of oil, coal and natural gas. In one scenario, nuclear energy is phased out by 2100 whereas in the other some nuclear power is retained. Overall primary energy consumption increases to 880 EJ by 2100, just over twice the 2000 level.

The WEC authors conclude that, judged in terms of their sustainability, one of the High Growth scenarios (the third) includes many elements favouring sustainable development, though the other two High Growth scenarios do not. The Middle Course scenario, however, falls short of fulfilling most of the conditions for sustainable development.

The Ecologically Driven scenarios, unsurprisingly, are much more compatible with sustainable development criteria, although one of them requires a more radical departure from current policies since it envisages a phasing-out of nuclear energy.

The overall message of the WEC scenarios, examining possible solutions at a world scale, is similar to that of the RCEP scenarios for Britain: that progress to much greater sustainability in our energy systems is feasible over the next 50–100 years; that there are a number of different paths to sustainability; and that some paths are probably better than others.