1.2 Factors that influence decisions

Now that these different approaches to decision making have been considered it is possible to extract a number of linked factors that influence decisions:

- The decision makers

- The decision situation

- Thinking in terms of a problem or an opportunity

- Decision criteria

- Time

- People affected by the decision

- Decision support – theories, tools and techniques.

Let us briefly consider each of these factors in turn.

1 The decision makers

Different people approach decision making in different ways. Individuals are unique in terms of their personalities, abilities, beliefs and values. They also each have traditions of understanding out of which they think and act. Even when the same data is apparently available to all, people will interpret and assimilate the data in different ways and at different speeds. Some people are very confident about weighing up a situation and making decisions, others less so. Some like to take more risks than others. Competences, such as the ability to listen to other people, also vary. Social pressures affect everyone to varying degrees and the approval or disapproval of friends and colleagues may be more important to the decision maker than being ‘right’ every time. Political beliefs also vary and people will rank differently, for example, individual and social gains from a situation.

Each individual develops personal beliefs and values, including those relating to their environment, through different life experiences, and hence brings a different perspective to a decision situation. Some people will also have more at stake in a decision outcome than others. There are therefore many issues around who is involved in decision-making processes and how they participate.

2 The decision situation

The garbage-can approach to decision making showed that the decision situation is often messy and complex and that apparently unrelated events can affect decision outcomes, depending on what else is going on at the time the decision is taken. For any individual or group there will be both ‘knowns’ and ‘unknowns’ in a decision situation. In the examples so far, in the text and in the answer to Activity 1, the unknowns range from prices and models of computers to weather conditions and availability of people. It is not always easy to work out which aspects of a decision situation are relevant.

Elements of change, risk and uncertainty are common in decision situations and recognising and making sense of these elements are two of the main challenges that decision makers face. Risk implies that we know what the possible outcomes of a decision may be and that we know, or can work out, the probability of each outcome. Uncertainty, on the other hand, implies that there are unknowns and that we can at best guess at possible outcomes and their probabilities or consider a range of imagined scenarios. There are ways of reducing some of these unknowns by using relevant data, techniques (for example, ‘what if’ modelling) and the experience of participants. Many of the ideas and techniques outlined in this course are intended to help you recognise and evaluate different aspects of decision situations, to work out which are relevant and what you can do about them.

3 Thinking in terms of a problem or an opportunity

When you have started to consider an issue and are approaching a decision, do you think in terms of opportunities, problems or both?

A potential problem can often be turned around by thinking about it differently.

For example, Shields Environmental in the UK has developed a business that provides two specialist services – reuse/recycling of mobile phones and reuse/recycling of telecommunications network equipment. Fonebak was one scheme they have developed. It was the world’s first mobile phone recycling scheme to comply with all legislation. Over 18 million phones each year were being replaced in the UK around 2000 and without opportunities for reuse and recycling would have probably gone as potentially hazardous waste to landfill. In Fonebak’s first two years of operation (2002– 04) the company processed 3.5 million mobile phones for reuse and recycling, from 10,000 collection points across Europe. Many phones were reused to provide affordable communication in developing countries and those that could not be reused were recycled, with their materials put back into productive use. In taking up this opportunity Shields Environmental has not only developed a successful business but also enabled others to comply with environmental regulations.

Robert Chambers, in his book Challenging the Professions (1993), argues that there are two main disadvantages to thinking of a situation as a problem rather than as an opportunity. First, it has negative connotations, and second, it can lead to misallocation of resources if we think in terms of problem solving rather than seeking out new opportunities. Problems and opportunities seem to have other characteristics also, which are listed in Table 1. Do you agree with them? Can you think of any others?

| Problem | Opportunity |

| Negative connotation | Implies positive action |

| Often used with adjectives like ‘worrying’ or ‘difficult’ | Often used with adjectives like ‘exciting’ or ‘new’ |

| Needs solving? | Implies choice |

| Can confine both thinking and action | Can liberate enthusiasm for dealing with a situation |

| Recognises constraints | Recognises new directions |

| A situation of disadvantage | Turning situation to own advantage |

This is not to suggest that all problems can be turned into opportunities. One person’s problem may well be another’s opportunity, which will not always help the person with the problem. But it is worth remembering that how a decision-making situation is thought of can affect what actions are taken, and that there might well be opportunities in what appears to be a problem situation.

4 Decision criteria

The criteria that are established and used to evaluate alternative courses of action in decision making will certainly affect the outcome of a decision. Different criteria will be appropriate in different situations but are often needed both to help make a decision and to make apparent the basis on which it is made.

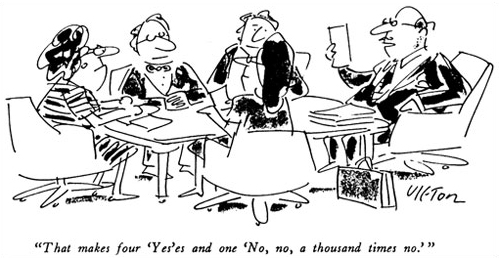

In group decision making, exploring and deciding on criteria is one way of developing a shared understanding of a situation. Different decision makers with different beliefs and values are likely to identify different criteria and give a different weighting to them (see Figure 1). For example, finding an option for a new housing site that will satisfy (a ‘good’ decision) or at least satisfice (an ‘adequate’ or ‘goodenough’ decision) all those involved will usually mean compromises or trade-offs.

Specific criteria can help to identify areas where there is agreement and disagreement. Criteria for the new housing site might include, for example, how existing land use is valued and by whom, services and housing provision available in the vicinity, likely disturbance or enhancement of the area and implications for road safety. There will be different views on what is acceptable for each of these aspects and often a need for negotiation. Criteria such as these are frequently worked out at different levels, as part of the regional as well as more local planning processes.

5 Time

A decision is made at a particular time in a particular set of circumstances. The decision situation can change very rapidly so what appeared to be a rational decision at one time might later appear to be anything but that.

One aspect of the time dimension that is particularly apparent in the ‘garbage-can’ decision-making approach is that the outcome of a decision may be affected by concurrent, but otherwise only marginally related, events. One example of this might be the unexpected availability of additional resources or a reduction in resources because of another project going on at the same time elsewhere. Another example might be the way that strong opposition to, or support for, a new development may unexpectedly surface because of events elsewhere.

Time is also a factor that can affect the nature of people’s participation in decision making. Skills are needed to be able to judge the urgency of decision-making processes, who needs to be involved in which stages of decision making within a particular time and resource frame and to what extent timing can be negotiated and with whom.

6 People affected by the decision

People who are likely to be affected by a decision can have considerable direct or indirect influence on the outcome of a decision. There are many ways in which this can happen. People affected might be ‘shareholders’ or ‘stakeholders’. Shareholders’ interests are economic; stakeholders’ interests in the decision are much broader than economic. Stakeholdings may be direct or indirect. Ways in which people affected can influence the decision range considerably. They may participate actively or proactively from the start, for example by being involved in the design of decision-making processes or in deciding on policy, or at other stages, e.g. through campaigning to try to overturn specific planning decisions, such as road building, industrial or housing development, or participate passively by withdrawing cooperation after the decision has been reached, such as refusing to use a facility that has been provided. There are issues of power to take into account in considering the nature of the influence that people affected by a decision can have.

7 Decision support – theories, tools and techniques

Many theories, tools and techniques have been developed to support and explain decision making, for example in medical, legal and organisational contexts. They may offer support to decision-making processes, depending on how they are used. For instance, the ability to model aspects of a situation may address some of the information constraints mentioned in Reading 1. But note also that March (1991) commented that ‘any technology is an instrument of power that favours those who are competent at it at the expense of those who are not’.

Power relations, the role of different stakeholders and expertise in decision making and use of models for decision support must be taken into consideration. A great deal of literature also exists on areas such as decision theory and behavioural research on how decisions are made.