3.2 Power relations and sources within decision making

A lot of conceptions of decision making include ideas about power relations. For instance John Heron (1989) identifies three levels of power to be consciously recognised in the process of project or activity design:

- Hierarchical, with ‘power over’ leading to ‘deciding for’;

- Cooperative, or ‘power with’, leading to ‘deciding with’;

- Autonomous, or ‘power to’, leading to ‘delegating deciding to’;

Of course there are many issues associated with each of these categories, for instance in how a process of delegation may be experienced. But the idea is one of an increasingly ‘bottom up’ rather than ‘top down’ approach. One outcome of a ‘power to’ level of power may just be that stakeholders can get on with work or activity rather than waiting for someone else to decide. The previous unit discussed some situations where power relations need to be considered in decision making. The two examples mentioned were how or whether people affected by a decision, such as one about a new development, can use their power to influence a decision and how people skilled at using a model use the power associated with their skill (e.g. to explore a context with others or to persuade others to take a particular point of view). Another example is one where some people have more access to and control of information than others because of their role or position. Heron’s categorisation could be used to consider each case to consider the power relations among stakeholders.

But where does power come from and how can it be generated in constructive ways? Ideas of power sharing or delegating (or not) often appear in news stories, particularly in relation to politics. Do they imply that there is only so much power to go round? Some ideas that may answer these questions come from Gary Klein, who wrote a book called Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (1998). Klein wrote this book to try and balance other books that concentrated on the limitations rather than the abilities of decision makers, particularly in difficult conditions. He had done a first study on how fire-fighters make life and death decisions under extreme time pressure and many subsequent studies (including pilots, nurses, military leaders, nuclear power plant operators) as part of a tradition of ‘naturalistic decision making’ where how people use their experience to make decisions in field settings is considered. Klein and his colleagues found that

[P]eople draw on a large set of abilities that are sources of power. The conventional sources of power include deductive logical thinking, analysis of probabilities, and statistical methods. Yet the sources of power that are needed in natural settings are usually not analytical at all – the power of intuition, mental simulation, metaphor and storytelling. The power of intuition enables us to size up a situation quickly. The power of mental simulation lets us imagine how a course of action might be carried out. The power of metaphor lets us draw on our experience by suggesting parallels between the current situation and something else we have come across. The power of storytelling helps us consolidate our experiences to make them available in the future, either to ourselves or to others.

The criteria for Klein’s ‘naturalistic decision-making settings’ followed those identified by Orasanu and Connolly (1993), i.e. time pressure, high stakes, experienced decision makers, inadequate information, ill-defined goals, poorly defined procedures, cue learning (where patterns are perceived or distinctions made that lead to a next stage), performed within a context of higher-level goals and different tasks with their own requirements, dynamic conditions and team co-ordination.

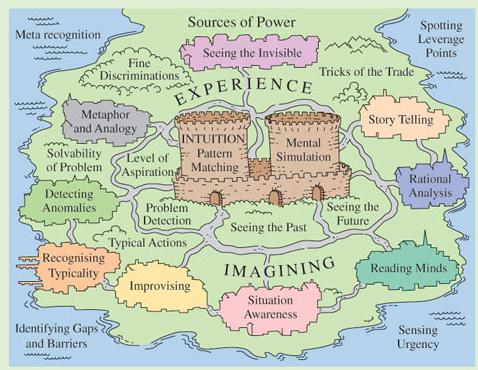

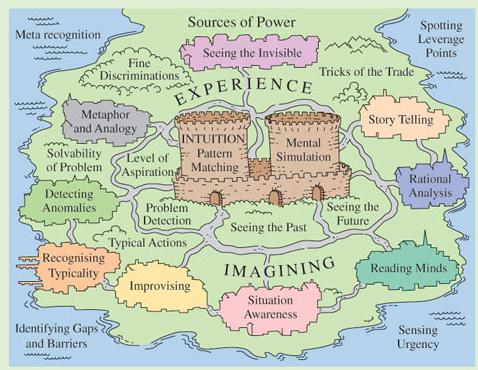

The diagram below captures some of the ideas that Klein explored.

Klein has written a full book about these sources of power and I cannot hope to capture the richness of that book here. However his diagram, Figure 1, can be thought of as a ‘rich picture’, particularly if considered with his explanation of why he has drawn the diagram the way he has:

There are many different ways to connect all of these sources of power. Figure 1 presents one framework. Here, the two primary sources of power are pattern recognition (the power of intuition) and mental simulation. That is why they are so prominent. Storytelling seems to rely on the same processes as mental simulation, so it is tucked in next to it. The use of metaphors and analogues seems to rely on the same processes as pattern recognition, except that in pattern recognition the specific metaphors and analogues have become merged, so these two are pushed together. These are the four sources of power that refer to processes, to ways of thinking.

The other three sources of power are based on the first four, so they are arranged further into the periphery. These three refer to activities – ways of using the four processes at the base. Expertise (the power to see the invisible) derives from both pattern recognition and mental simulation. The ability to improvise in solving problems also derives from pattern recognition and mental simulation. Our ability to read minds depends on how well we can mentally simulate the thinking of the person. The additional sources of power are arranged according to the same sense of family resemblance. Figure 1 is a concept map of the way I am viewing these processes.

Activity 13 Sources of power

Take some time to look at the diagram in Figure 1.

- (a) Choose one of Klein’s ‘sources of power’ as shown in Figure 1. Write a short account related to your own experience to indicate how you think it could work as a source of power.

- (b) What do you find to be missing from Klein’s diagram, from your own perspective? Make your own list of ‘sources of power’ in a decision-making situation familiar to you.

Discussion

(a) I have chosen ‘storytelling’ from Klein’s diagram. I have been to many conferences as part of my job, sometimes as part of the audience and sometimes as a presenter. I have noticed that stories of people’s experiences or events that they have experienced, if told in an engaging way, have sometimes stayed with me much longer than presentations in other forms. I have had feedback from people who have listened to my own presentations to indicate that others sometimes experience stories in a similar way. I have also listened to many presentations that have failed to engage my attention. I think it’s tempting to think that a conference presenter is in a position of power and that their voice will be heard because they are presenting. But my experience is that it is only the presenter who has the ability to engage an audience who will be heard, and in turn be able to influence others, using storytelling as a source of power.

(b) I felt there was more to simulation than just ‘mental’ simulation and being able to imagine what might happen in decision-making situations I have experienced. I think I can see how that is a source of power at an individual level, but when working in groups, more explicit simulation or articulation of ‘seeing the future’ may be needed. Perhaps this would be done in modelling a series of possible shared scenarios, so it’s not just about seeing the future but about modelling possible futures together with others? But perhaps I am also thinking of some rather different decision-making situations here from Klein, with less immediate time pressures? I am thinking of a decision-making situation regarding moving house. My list of some of my sources of power for this decision-making process would be:

- imagining the future;

- support of others in my household;

- knowledge of my potential resources (e.g. money, time);

- knowledge of housing market and locations;

- rational analysis of my options, circumstances and likely future circumstances;

- intuition.

In terms of John Heron’s three levels of power mentioned at the start of this section, Klein’s work is mainly about the autonomous level of power. Many people may be able to draw on, for instance, the power of intuition, storytelling or metaphor to gain insights into a situation. But if working in a hierarchical or even a cooperative context, where power is derived from position or reputation, they may not be able to act to improve the situation.