4.3 Recognising change and learning in decision situations

Decision situations are constantly changing; they are usually dynamic not static. Data on biological and physical processes and human activity, and statements about action being taken to address environmental issues, are obtained at a particular time and in a particular context. Keep in mind that there is a need for caution in interpreting data or statements that originated in a different context or era. Another aspect of change in decision situations concerns learning.

Experiential learning

Have you ever read a book about a place you have never visited that has meant little to you but returned to the book later after going there to find it meant something quite different?

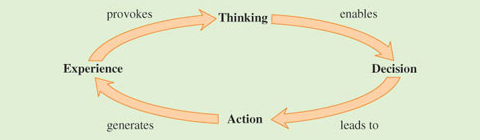

The same principle can apply when trying to understand the context of your environmental decisions. Accounts of what is happening might well be available but you do not fully understand them. We learn from our own experiences. It is difficult to identify with a problem or an opportunity unless you have experienced some part of it yourself. For example, we can all identify with some activities that have an effect on our environment, such as transport and use of packaging, because we have at least a consumer’s perspective. But our experiences may well be very different. For example, people whose livelihood is connected with the transport or food sector are likely to identify with them even more strongly. Identifying with the problem or opportunity is a step towards ‘owning’ it, but this does not always happen if people do not recognise it as ‘their’ problem. Recognising that we learn from our experiences is particularly important in environmental decision making because our experiences affect the way we think about a situation, which in turn influences our decisions and actions. This type of learning is an iterative, or recurring, process as illustrated in Figure 11.

The experiential learning cycle is just one model of how we learn. This version is adapted to show the place of ‘decisions’ in the cycle. The original experiential learning cycle was developed by David Kolb and Roger Fry in 1975 (Kolb and Fry, 1975; Kolb, 1984), building on the work of Kurt Lewin, who is better known for his work on action research. As with any model, there are assumptions embedded within it, for instance that the activities identified are the only ones involved in experiential learning and in the order of activities. Other theories of learning have identified other processes. Changes in behaviour, changes in a learner and changes in learners’ relationships with others and/or their environments may all provide evidence of learning depending on how learning is theorised (Brockbank and McGill, 1998).

The cumulative environmental impact of individual decisions is often very large, so while each individual’s effect may in itself be small, it is still a contributory factor. It is important for all those involved to take responsibility for their actions. In understanding environmental decision making, it is also important to recognise the need to learn and make decisions in groups as well as individually. To be able to do this we need to listen to and try to understand different perspectives as well as just considering our own.

In the context of environmental decision making, learning what changes to make and how at both individual and social levels is important.