5.1.1 The case study

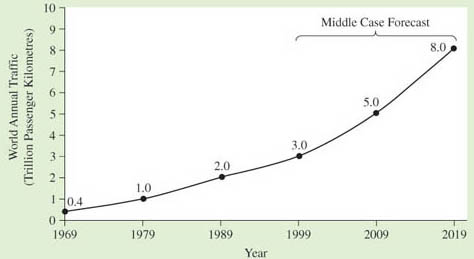

I readily volunteered to write this case study because of my personal stake in aviation, living only 15 minutes away from Heathrow Airport in the South East of England, and often jumping at any chance to get out of this relatively cold and wet country (and then enjoying my guilty conscience at leisure on some hot tropical beach). I have to confess that I have only recently begun to take the environmental impacts of aviation seriously. The car was, and probably still is, the environmentalist’s transport enemy number one. But the enormous expansion in air travel within the last half of the 20th century, almost doubling every ten years, and the sustained expansion forecast for the first half of the 21st century (see Figure 12) means that major environmental impacts will no longer be limited to the surroundings of international airports. As I write this in 2005, there are over 18,000 commercial aircraft providing in excess of 3 billion passenger kilometres between 1192 airports worldwide. Yet, only 5% of the world’s population has ever flown. Reductions in costs and the expansion of airport capacity will allow a significantly greater proportion of the world’s population to fly. But at what cost to the environment and to the well-being of those living near airports? Is it time to limit people’s freedom to fly?

Aviation is one of the most environmentally damaging modes of transport at our disposal today. It contributes to greenhouse gas emissions that are generally accepted as causing global warming. It can adversely affect those living near airports (both in terms of noise and air quality) with many airport workers, especially those in the developing world where health and safety regulations are not as strict and/or implemented, being exposed to toxic levels of exhaust fumes and vaporised fuel chemicals. Airports produce a significant amount of solid and liquid waste and are a drain on surrounding natural resources such as water. But this perspective focuses just on the environmental impacts of aviation. Taking a different perspective, there are significant social and economic benefits. Many people love exotic holidays in far away places, and buy products flown all the way from the other side of the world. Business people in the ‘global economy’ need to meet face-to-face to clinch deals. And the millions of people employed by the worldwide aviation industry and the associated industries, such as tourism, appreciate the money they receive as a result. The socio-economic demands are such that, if unconstrained, aviation in the UK alone is forecast to double in the next 30 years.

Airport expansion is now a major local issue (for those living near airports) and a global issue (as a result of its increasing contribution to climate change). The authors of this unit felt that aviation and airport expansion was a good example of a complex, interconnected decision-making situation. But the subject is vast, and in order to provide an example case study with sufficient depth and a clear boundary, we have focused on the decision-making process leading up to the ‘Aviation White Paper’, a strategy paper published by the UK government (terms like ‘white paper’ and other aspects of the UK government’s legislative process are explained in Box 5 in Section 5.3). My account of the ‘Aviation White Paper’ process explores a major event in recent history with environmental decision making at its heart. The paper aimed to set out a strategy for airport expansion in the UK for the next 30 years, while taking into account the environmental impact of expansion.

Activity 18 How does aviation affect you?

Before we delve into the ‘Aviation White Paper’ case study, I would like you to explore how you think aviation is affecting you personally. Below are a series of more detailed questions that may help you explore this. Note your answers in your learning journal.

- Over the last few years, how many flights do you think you have taken?

- Do you consume or produce any goods that you think require air transportation?

- Who do you think has benefited from your journey and/or consumption?

- What environmental impact do you think these have had?

- If you are one of the 95 per cent of the world’s population that have never flown before, or if you have already flown but feel that you would like to fly a lot more, what constraints do you think are limiting your use of air travel?

Discussion

There’s no standard response to this activity as you will be drawing on your own experience, but to give some examples of points to think about I have briefly included my attempt at this activity. I have selected 2005 as the time period for my response.

In 2005, I flew from several London airports to Edinburgh, Scotland (for a conference), to Georgetown, Guyana (for research), and to Naples, Italy (for Christmas with my family). I wanted to calculate an approximate value of the carbon dioxide emissions resulting from my travels. To quantify this impact, I used an ‘Air Travel Calculator’ that I found online. I was surprised to discover that my three journeys produced similar carbon dioxide emissions to a whole year of car use. In 2005, I drove approximately 16,000 kilometres, which produced around three tonnes of carbon dioxide compared to the 2.5 tonnes emitted by my three air journeys.

In terms of constraints to flying, I am part of an extremely small proportion of the world’s population that finds it easier and cheaper to fly to the other side of Europe than to get public transport from my home to my place of work! I live within a 90-minute drive of all London airports and could readily find an offer to a European destination for less than £20 return, and I have no entry visa restrictions to any European country. Whereas it takes me six hours and £23 to get to work and back by train and bus (even though it is only a distance of 90 kilometres).

In fact, I live very close to Heathrow airport (a 15-minute car journey on a good day), so my family experiences the noise, disruption and traffic congestion (with the associated air pollution) on a daily basis. On the other hand, at least four of my neighbours work at Heathrow airport so I appreciate the economic contribution to my local community, although I am worried about the increases in living costs (such as house rental) if Heathrow airport expands further.

Although I grow most of the vegetables we consume, I do occasionally buy produce such as tropical fruit and flowers, which I know have been flown in.

Be aware that the figures provided here in my response to the activity are very rough approximations. There are some very significant implications in the online carbon emission calculations. For example, the calculations for air travel use only a single aircraft type with a standard number of passengers. The age and size of aircraft you fly in, and the number of passengers in your particular journey, will significantly affect the actual emissions per passenger. So I would always recommend that you question the assumptions behind any modelling.

This activity may help to demonstrate what your personal stake is in aviation. But your decision to fly and/or buy flown-in goods, and the constraints that may limit your flying, are not isolated. They are helped and hindered by other decisions made by other fellow travellers (friends, colleagues, employers), airline companies, airport operators, travel agencies, industries dependent on air transport, environmental nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), specialist consultants and a multitude of government departments, to name a few influential stakeholders in air travel. My interpretation of the ‘Aviation White Paper’ focuses on the process created by the UK government and how the voices of the various stakeholders have been represented (or not).