6.6 Hormones and hibernation

6.6.1 Melatonin

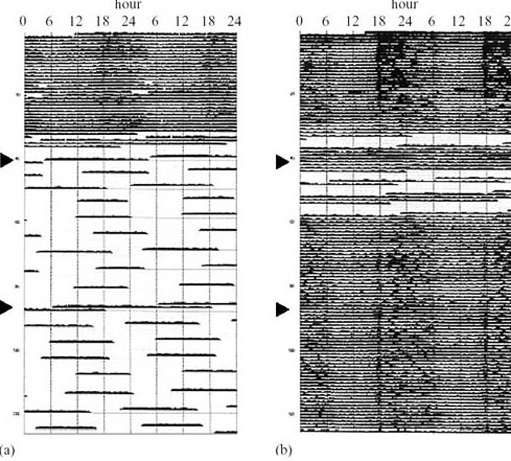

Syrian hamsters, which display pronounced circadian temperature fluctuations before hibernation, lose these circadian cycles on entry to hibernation, and start to regain them shortly before arousal. Cycles are distorted during the early recovery period, suggesting that the SON oscillator has either been switched off or de-synchronized in hibernation. Another monoamine, melatonin, is involved in making these adjustments. A hormone rather than a neurotransmitter, melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland on the dorsal side of the brain. Removal of this gland can cause disturbances in both the ‘clock’ and the ‘calendar’ settings of mammals. Melatonin travels both to the pre-optic area of the hypothalamus, where it can reset the set-point for Tb, and to the SON where it can adjust circadian and seasonal rhythms. Continuous infusion of melatonin inhibitor into the circulation from subcutaneous implants can lead to a decrease in the duration of bouts of torpor in hibernating ground squirrels (Figure 42) (Pitrosky et al., 2003). A second important function of melatonin is to inhibit sexual activity and the production of gonadal steroid hormones through the mediation of the pituitary gland, which is itself under the control of neurons within the hypothalamus. Both events appear to be under the principal control of the SON, since its destruction by electrolytic lesions leads to an impairment of circadian rhythms and the ability to hibernate. More recently it was shown that an inhibitor of melatonin, on the other hand, can decrease the duration of hibernation by reducing both the number of hypothermic bouts and the amount of lipid present in BAT.