4.3 Humans in polar regions

Humans evolved in tropical Africa and gradually colonized colder climates during the Pleistocene ice ages. There have been permanent populations in the Arctic for several thousand years, mostly Inuit (Eskimos) in what are now Canada, Alaska and Greenland, and several groups in northern Europe and Russia, such as the Saami (Lapp) in Scandinavia and the Chukchi in Siberia. Such people do not grow crops and keep only a few domestic animals, mostly for transport (e.g. husky dogs or reindeer), not for food. Until very recently, they lived by hunting seals, walruses, polar bears, fish and wild and semi-domesticated reindeer and, during the brief summer, gathering wild berries.

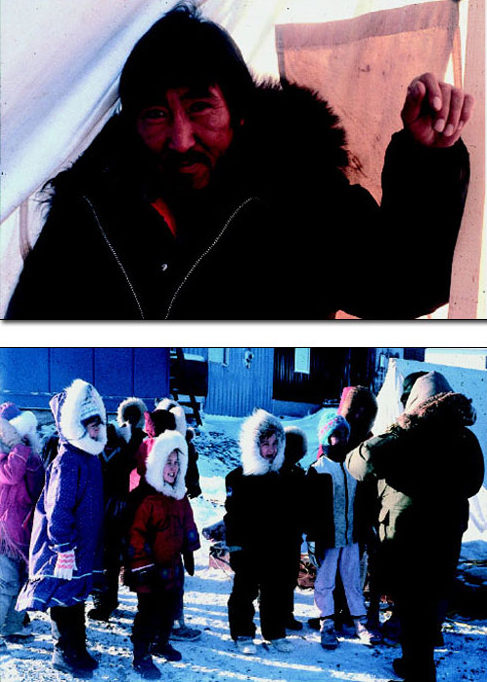

Adaptation to living in the Arctic has been more technological and cultural than physiological: Inuit (Figure 22) are shorter and stockier than Canadians of European ancestry, but comparisons of the distribution and abundance of their adipose tissue revealed that the native people have less, rather than more, superficial fat.

SAQ 32

What does this comparison suggest about the function of superficial adipose tissue in humans?

Answer

It is not adapted to a role as thermal insulation. Frost damage to exposed parts such as the face and hands is prevented by efficient perfusion with warm blood (see Figure 18), rather than by any form of insulation. Human colonization of the Arctic was made possible by the effective use of animal skins as clothing.

Adaptations of digestion and metabolism have evolved among Inuit: although their diet was very rich in fat and protein, and for 9 months of the year included almost no fruit or vegetables, diseases such as obesity, diabetes, scurvy, rickets, dental caries, constipation and colon cancer were rare. However, obesity, diabetes and dental caries have become much more common during the last 40–50 years since they adopted a western diet. Inuit have never grown or stored crops, and so alcoholic drinks produced from fermented carbohydrates (i.e. grain, potatoes, fruit or sugar) were never part of their diet: alcohol dehydrogenase, the enzyme that detoxifies alcohol, is present in very small quantities in their livers and it is not as readily induced as it is in people whose ancestors have a long tradition of drinking alcoholic beverages. Consequently, grown men are easily intoxicated by as little as 0.25 l (half a pint) of beer.

The capacity of the human nose to conserve moisture by warming and hydrating inhaled air and reclaiming the heat and moisture of exhaled air (shown in the dog and bear in Figure 18), is much less efficient than the long nasal turbinals of native arctic mammals such as bears, reindeer and wolves. The ability to breathe steadily through the nose rather than through the mouth improves with practice, but most inexperienced visitors to polar regions are bothered as much by thirst as by cold.

Living in such a severe climate is very tough: archaeological studies suggest that human habitation of arctic regions was often transient, with many settlements being abandoned when the climate worsened or food became scarce. Until very recently, resources were never abundant enough to support the development of large, dense cities or towns.

People from the temperate zone have only recently explored the high arctic regions, attracted by opportunities for hunting fur-bearing animals (seals, bears, beaver, lynx, wolves, arctic fox, musk rat, otters), and whales and other marine mammals for their meat and oil, and the search for gold, crude oil and other minerals. European expeditions, such those led by the Dutch sea captain, Willem Barents, in 1596–1597 and by the Russian-financed German explorer, Vitus Bering, in 1741, visited the Arctic Ocean and many of its islands, including the Svalbard Archipelago (see Section 1.1). Sir John Franklin led several British expeditions to northern Canada and the islands off the north coast, starting in 1819. Although equipped with the latest ships and extensive provisions, and assisted by the Inuit, Franklin and almost all his crew died on the final journey. Their primary objective, to find and map the North-West Passage from Europe to Asia, was never realized. No permanent settlements of Europeans were established in the high Arctic until the 20th century.

There is no pre-historic evidence for humans on Antarctica. The voyage of Captain James Cook in 1772–1773 is the first known exploration of the Southern Ocean. Fisherman and hunters of whales and seals landed on many of the islands during the 18th and 19th centuries, but Antarctica itself was not explored until the first decade of the 20th century. Although research in and around Antarctica has been much expanded since the 1960s, there is still no permanent, breeding human population.