1.1 Woodland structure

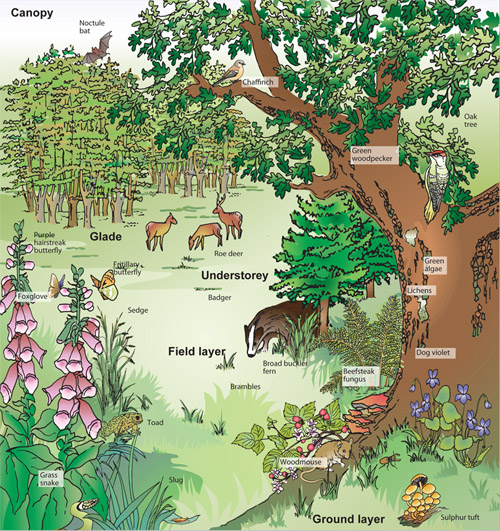

Most woods have a number of vegetation layers (Figure 1). There is the canopy, or top layer, where the tallest trees are found, such as oak (Quercus robur), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), beech (Fagus sylvatica) or birch (Betula pendula). These trees receive the maximum amount of light available.

The understorey is composed of shorter trees or shrubs, such as field maple (Acer campestre), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) or hazel (Corylus avellana), which are adapted to grow successfully with less light, as well as saplings of canopy tree species.

The herb or field layer may include ferns such as the broad buckler fern (Dryopteris dilatata), flowering plants such as the wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) and grasses.

The ground layer is composed of mosses, lichens, ivy (Hedera helix) and fungi. On the woodland floor there is usually a layer of rotting leaves and vegetation, which is home to a range of invertebrates such as springtails (Collembola), woodlice (Oniscidea) and millipedes (Diplopoda).

Climbing plants, such as honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), grow up tree trunks to reach towards the light. Others, such as certain mosses, lichens and ferns, grow attached to tree trunks in order to reach light – they are epiphytes, plants that grow on other plants only for support and do not obtain nutrients from them.

Question 1

If light is so important for plant growth, how do you think species such as bluebells manage to survive growing under dense shade?

Answer

Species such as bluebells survive under the shade of the canopy because they normally complete their life cycle in early spring, before the leaves fully open in the tree canopy above. Other species are simply tolerant of shade or grow in the parts of the woodland that receive more light, such as gaps between trees, glades or at the woodland edge. Coppicing encourages such species.