1.1 The structure of atoms

To gain a good understanding of the processes behind nuclear energy and radioactivity, you’ll need first to consider the atom.

What are atoms?

If you look around you all the matter in the world is made up of very tiny building blocks called atoms.

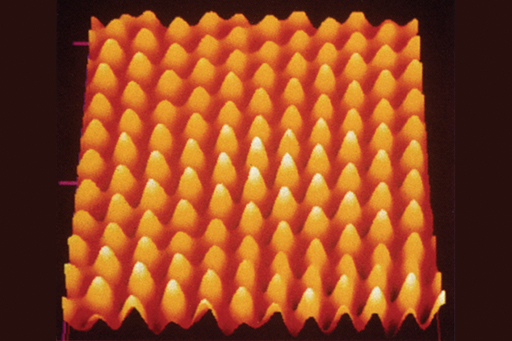

Atoms are very small. The diameter of an average atom is a ten-billionth of a metre (or 10-10m if you are familiar with scientific notation). This means that 10 million atoms would fit between a millimetre division on a ruler. It is only recently that technology has progressed enough to enable us to see atoms. Figure 1 was produced with a type of microscope that enables us to distinguish individual gold atoms.

Different types of atoms combine in a number of ways to form the varying substances of matter. You might think there would need to be a huge number of different sorts of atoms to account for all the substances that exist and that can be made, but in fact there are just 118 different types of atom that have been observed. These are known as the chemical elements and of those 118, only about 90 occur naturally. Each element is represented by a chemical symbol, consisting of one or two letters, for example, H is for hydrogen and He is helium. An element important in Week 2 is uranium (U).

What is inside an atom?

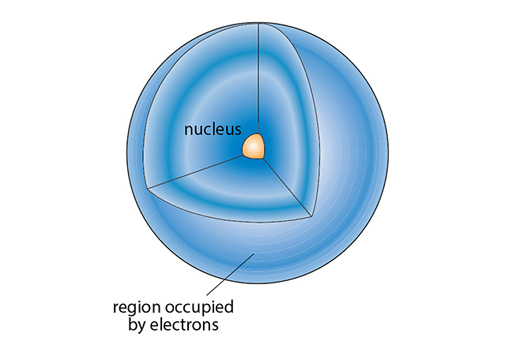

At the centre of an atom is a nucleus. If the atom was the size of a football stadium the nucleus would be the size of an orange at the centre! The diameter of a nucleus is about one ten-thousandth of that of an atom (or 10-14m). Pretty much all the matter in each atom is concentrated in this tiny volume and so nuclei are super dense and packed with energy. In this course we will be concerned with nuclei (NB nuclei is the plural of nucleus) and the release of this energy.

The nucleus itself is made up of smaller particles called protons and neutrons. These have similar (and very tiny) masses. The proton is positively charged and the neutron is neutral giving an overall positive charge to the nucleus. Protons and neutrons can be referred to collectively as nucleons.

The rest of the atom is taken up with the orbital electrons. These are much lighter than the proton or the neutron and are negatively charged, balancing out the positive charge of the nucleus.

What is an element?

Much of the matter around you is made up of compounds. Compounds are made up of molecules where there are two or more different atoms bonded together. Elements are made up of just one type of atom. You may be familiar with the periodic table [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] which gives the full list of elements.

The number of protons in the nucleus of an atom is known as its atomic number and given the symbol Z. It is this number that determines the chemical element. Elements are defined by their chemistry, and chemistry is all about the interactions of the electrons of the atom, not the nuclei. The number of electrons in a neutral atom is always the same as the number of protons in its nucleus.

You may be wondering what role neutrons play and you’ll find that out in the next section.