5 Political settlement theory

In the following video, Giles Mohan introduces the idea of ‘elite bargaining’ and ‘political settlements’ using the example of Ghana to show why ‘good institutions’ are not enough.

Transcript: Video 2

When studying China’s engagement in Africa the analysis invariably focuses on political elites. Elite-based political coalitions are central to the political economy of oil and development, wherein the nature of the ruling coalition at the moment when natural resources are discovered has important implications for how and in whose interests those resources are governed. In analysing the role of elite coalitions in the political economy of resources, we use the concept of political settlements. For Mushtaq Khan, a ‘political settlement emerges when the distribution of benefits supported by its institutions is consistent with the distribution of power in society, and the economic and political outcomes of these institutions are sustainable over time’ (2010, p. 1). By focusing on the underlying power arrangements that underpin the emergence, stability and performance of institutions, political settlement theory pushes development thinking beyond an institutionalist approach to understanding the resource curse.

Political settlements theory focuses on how the balance of power in a polity between different groups shapes the types of institutions that emerge and how such institutions function in practice. An important contribution of this concept is the primacy it accords informal institutions for understanding governance and development outcomes in developing countries, where the clientelistic nature of politics is widely acknowledged. Khan (2010) sees clientelism as the most pervasive form of politics in developing countries because the formal productive economy is not developed enough to allow allocation of resources through more formal mechanisms. In turn, tax revenues are insufficient for redistribution, which means that political coalitions rely on selective and informal political mechanisms to survive. Developing countries are therefore characterised by ‘clientelist political settlements’ (Khan, 2010). In this sense, clientelism is not a vestige of ‘pre-modern’ forms of politics, but is a rational mode of politics, given the need to ensure the stability and viability of the ruling coalition.

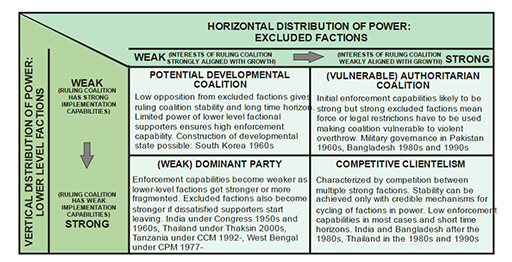

Khan further argues that the differing levels of capacity and commitment of ruling elites to delivering development are explained largely by the strength of excluded elite groups and of lower-level factions within ruling coalitions. In particular, where factions with significant holding power are excluded from the ruling coalition, then those in power are vulnerable to threats to their rule, which in turn reduces the likelihood that they will undertake institutional reforms and distribute resources in the national interest. In contrast, where excluded elite coalitions are weak, the ruling coalition will consider itself secure enough to develop a longer-term vision for the nation.

Drawing on this, Levy (2014) distinguished between two main types of political settlements: those where there is a ‘dominant party’ or ‘dominant leader’, which has very little chance of losing power, and those characterised by ‘competitive clientelism’, within which there is a high degree of competition and a strong likelihood of power changing hands through the electoral process. These different settings create differing pressures on elites, including the time scale over which they are incentivised to invest in building formal institutions that operate in the public interest. Under competitive clientelism, for example, the vulnerability of those in power means that ‘the ruling coalition… has a short time horizon and weak implementation and enforcement capabilities’ (Khan, 2010, p. 8) and so relies on informal deal-making to survive.

Sam Hickey, Professor of Politics and Development at Manchester University, has been using political settlement theory within the ESID (Effective States and Inclusive Development [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ) programme of research, which is a global partnership investigating the kinds of politics that promote development. In this short video, taken from an online lecture – ‘What do you get from a political settlement perspective?’ – Hickey expands on some of the key points of this approach. While he explains the evolution of the thinking behind the theory – the rise in recognition that elite bargaining, the distribution of power and informal political arrangements, such as patronage, play critical roles in the governance and institutional effectiveness in many developing nations – what rationale does he give for why their programme of research chose the theory? In particular, towards the end of the video, Professor Hickey stresses that elite bargaining is not just a material and rationale decision-making process but that political elites can be driven by ideational aspirations and values for a ‘better’, developmentally progressive society.