2.1 The ‘It’s my money’ response (part 1)

Some people believe that others should not have donated their money to the Notre-Dame restoration fund. On the previous page, you read about two arguments in favour of this conclusion.

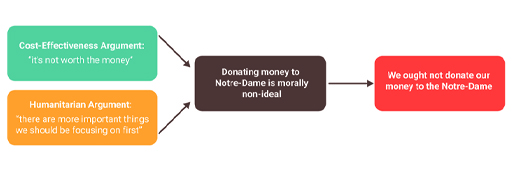

The first ‘cost-effectiveness argument’ is that restoring the cathedral is simply not worth the money: the cost of the project is greater than the value we might expect to produce. The second ‘humanitarian argument’ is that the value of Notre-Dame can never outweigh the value of human lives. Thus, given that there are human beings in need, our charitable donations should always go towards helping them before being spent on projects such as heritage-restoration (Figure 11).

And yet, people may disagree with the above argument. Even if donating money to Notre-Dame’s restoration is not morally ideal, arguably it is still permissible. In other words, we would not be breaking any moral rules or obligations by donating to the Notre-Dame appeal, even though there are other options which would be better, ethically speaking.

Activity 4 Defending donations to Notre-Dame

Think about the idea that donating to the restoration project is morally acceptable, even if it is not the best choice from an impartial, ethical perspective. What are some of the reasons or motivations you could give to support this claim?

Discussion

There are a few points which could support the claim. Here are a few you might have considered (although you probably thought of others too).

‘It’s my money’

Arguably, we each have a right to spend our money however we see fit, provided that it is legal and doesn’t do actual harm. Assuming that we have acquired our money through just means, it is our rightful property and, within certain constraints, we should be allowed to dispose of it how we like. This means that you could donate it to a humanitarian charity or to the restoration of Notre-Dame, and either option would be morally permissible.

Relationships

Many people believe that we have a right to offer special treatment or concern to people, causes or things when we have a special relationship to them which others may not share. For instance, you may have a right to protect your own children rather than someone else’s, given the relationship you have with them as their parent. You may also have a right to help your friends above helping strangers.

Extending this, arguably, we are each entitled to live our lives in a way that respects our unique history and the special relationships we have with other people. But sometimes this can involve doing things which aren’t optimal in terms of impartial morality. Hence, if you feel you have a special connection to Notre-Dame – perhaps the building is meaningful to you because of certain personal experiences – then you have a right to donate money to its restoration, even at the expense of ignoring the needs of less fortunate human beings.

Overdemandingness

It has been argued that it is simply too demanding to expect people to always act in a way that is morally perfect or maximises moral goodness. Perhaps it is impossible for a human being to behave in this way, perhaps not (it depends on your theory of morality). But it would simply be too taxing if people had to live as absolute moral saints. Sometimes people are entitled to be held to less-than-perfect standards, or even to be a little selfish.

More specifically, assume that we did have a strict duty to live as moral saints. This would not only require us to select efficient humanitarian charities rather than historic-building restoration when we donate. It would also require us to donate all of our money to such charities – or as much as we can spare. It would be less-than-perfect, morally speaking, to donate to Notre-Dame. Similarly, it would be less-than-perfect to spend that money on a pint of beer or a cinema ticket for ourselves. Ultimately, we would have to live our lives on the poverty line, giving away all but the money we absolutely require for the most minimal form of subsistence living.

Assuming that it would be overdemanding to expect people to donate all of their excess income to humanitarian charities, we seem to be left with some degree of freedom. This freedom may well grant us permission to donate to causes such as Notre-Dame without having done something morally impermissible or unacceptable.