1.4 The constitutive reading (continued)

To clarify, you can think of the constitutive reading as comprising two broad claims. First, the only reason that biological lives are valuable is because we need to be alive in order to flourish. After all, a life is not worth anything if the person leading it cannot experience any flourishing (e.g. a life of nothing but torture would not be valuable for anyone). Therefore, the point of saving human lives is that those individuals have the opportunity to flourish. If there is no chance of this, there is no value and no point in saving the lives.

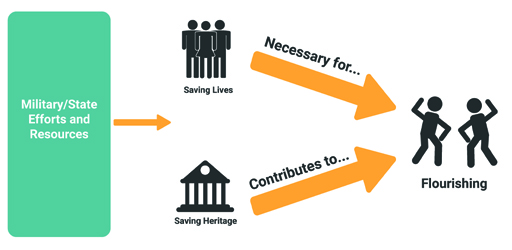

Second, cultural heritage is valuable for the same reason and only that reason: the worth of cultural heritage, and the point of retaining it, is because it helps humans to flourish. For instance, the beauty of a building, the connection it offers to the past, and its usefulness as a source of information – all of these things are worth preserving only because they contribute to our flourishing. If they did not, there would be no point in saving them.

If both claims are true – that biological life is only valuable as one essential condition for human flourishing and that cultural heritage is only valuable in that it also supports human flourishing – then you can see that the point of protecting heritage is indistinguishable from the point of protecting life. The goal of each claim is to maximise the amount of human flourishing in the world, so there is no genuine dilemma here. In that sense, the two projects are, allegedly, ‘inseparable’ (Figure 3).

This version of the constitutive reading aligns with many descriptions of cultural heritage. For instance, when Weiss and Connelly (2017) said ‘Air, water, and culture are essential for life’, they probably did not mean biological life but, rather, flourishing life. Similarly, when Vernon Rapley, Director of Cultural Heritage Protection and Security at the Victoria & Albert Museum, said heritage ‘makes the difference between living and life’, he presumably also meant to distinguish mere existing from valuable, flourishing life (Rapley, 2018).

This constitutive reading is better at incorporating the full range of values which are normally attributed to heritage, unlike the strategic reading which focuses only on the economic/force-multiplier benefits of heritage. It also provides a way to deny that saving heritage and saving lives can ever truly be in competition. Because the ultimate value of biological life and cultural heritage are identical, there is no need to make any philosophically difficult comparisons between the worth of each option. We simply make whichever choice would lead to the greater amount of human flourishing overall.