6.3 Word division

In a printed text, the gaps between words are as important for readability as the shapes of the letters themselves. This point is easy to appreciate if the gaps are omitted and the words squeezed together.

Try to read the following text. How easy or difficult do you find it?

THEWORDSAREEASIERTOREADIFYOUALREADYKNOWTHELANGUAGE

Perhaps you succeeded in making out most, or all, of the words at first glance. But you probably found the task a strain and were relieved to return to a conventional layout with spacing between the words.

THE WORDS ARE EASIER TO READ IF YOU ALREADY KNOW THE LANGUAGE

If you understand a language, you can generally puzzle out the word breaks yourself. For instance, English speakers know intuitively that the letters ‘rds’ cannot start an English word. They might appear in the middle of a word (like ‘wordsmith’), but are most likely to occur at the end, not least because ‘s’ is frequently tacked onto the end of nouns (‘cats and dogs’) or verbs (‘walks and talks’).

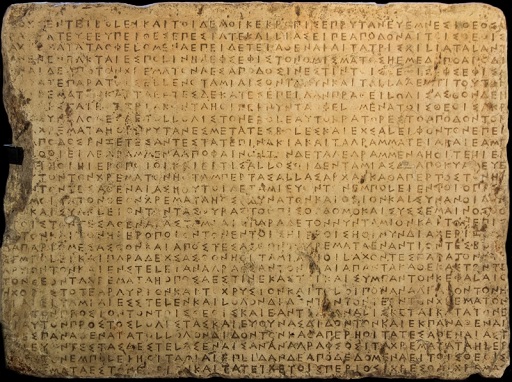

Activity 8 The Callias decree

Look at this inscription from fifth-century BCE Athens. You should be able to pick out a few letters, most of which are still legible. Consider the overall layout. Do you notice anything about the way the letters have been laid out on the stone, especially the horizontal and vertical arrangement?

Discussion

The letters have been laid out as if on a grid, in rows and columns, in a style known as stoichedon (‘row-by-row’, from στοῖχος, stoichos = ‘row’). To achieve this effect, the stone-cutter would have needed to plan the text carefully in advance to allow sufficient space. Once inscribed, a stoichedon text would be difficult to change, especially through the deletion or addition of letters, a fact which perhaps gave it an aura of reliability. The overall effect is rather imposing, appropriately for an official record of a decision taken by the Athenian state. Athens contained many such inscriptions.

This inscription is part of a decree passed by the Athenian assembly in the 430s BCE relating to Athenian financial administration. It is sometimes known, informally, as the ‘Callias [or ‘Kallias’] decree’ after the name of the man who proposed it.

Try to find the following words:

- The name of the proposer in the middle of the second line: ΚΑΛΛΙΑΣ ΕΙΠΕ (Καλλίας εἶπε, Kallias eipe = ‘Kallias said’).

- The reference to a sum of money, ‘3000 talents’, at the end of the third line, running over into the fourth: ΤΡΙΣΧΙΛΙΑ ΤΑΛΑΝΤΑ (τρισχίλια τάλαντα, trischilia talanta).