Preparing for your digital life in the 21st Century

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 3:28 PM

Preparing for your digital life in the 21st Century

Introduction

The profound technological, economic, political and ethical changes brought about by information technology will affect every one of us. You may be wondering what digitial technology is and just what is meant by having a digital life. A fundamental idea is that digital technology is any technology based on representing data as sequences of numbers. Computers use digital technologies; so the for benefit of this unit the term digital life refers to the influence of computers, in a wide variety of forms, on the world.

In this unit you will learn a little about the historical development of computers and their role in today’s society, and you will consider examples of digital technologies in the world around you and their influence on your life. You will also gain a better understanding of what makes a computer work by exploring what’s inside a typical personal computer.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course TU100 My digital life.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the concept of a ‘digital life’

demonstrate an awareness of the role of information and communication technologies in a digital life

describe the purpose of each of the major components of a computer system, and use common terminology to describe these components.

1 Computers: From novelty to commonplace

[Timings. This is the first section of this unit. It should take you around one hour to complete.] The theme of this section is the development of digital technologies, from the physically large and highly expensive equipment of the 1950s to the omnipresent networks and computer-based devices upon which our digital lives are founded today. In this section I will:

- compare the development of the computer to the development of the telephone

- describe some of the digital technologies that form an integral part of many of our lives

- introduce the term information society.

1.1 The telephone

In the 1950s, telephones represented the cutting edge of technology (Figure 1). However, they were not only large and expensive to purchase but also inconvenient to use; if you wanted to make a call over a distance of more than fifteen miles, you had first to call the operator who would then make the connection.

This black and white photograph shows an old design of domestic telephone from the 1950s.

Telephones were also expensive to use. In the UK, calls were charged in units of three minutes, each unit costing the equivalent of between 5 and 20 pence in today’s currency. (In comparison, in 1959 a pint of milk cost about 3 pence.) Few people had a home telephone and even fewer made long-distance calls. The high cost of using a telephone ensured that anyone who had one tended to use it infrequently, and then only for short calls.

In 1959 the General Post Office, which ran almost all UK telephone systems at the time, introduced subscriber trunk dialling (STD). This advance in technology allowed users to make long-distance calls directly, without an operator, and to be charged only for the actual duration of the call. The telephone became easier and much cheaper to use; as a result, more people began to use it and for longer calls.

Over time the telephone has become part of the background of our lives, until today it is extremely unusual to find someone who has neither a home telephone nor a mobile phone. Just as the telephone changed from a status symbol to become simply another piece of the modern world, so the computer is making a similar transition.

1.2 The computer

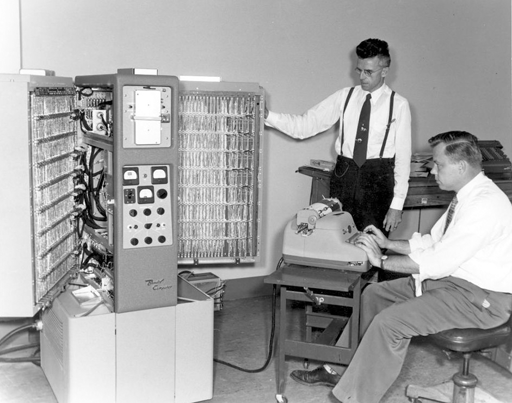

There were very few computers in the 1950s, and those in existence were treated as objects of wonder with almost mythical powers. They were nothing like the computers of today. For one thing they were huge, with the refrigerator-sized one shown in Figure 2 being relatively small for the time. They were also delicate, and consumed a lot of electricity, wasting much of it as heat.

This black and white photograph shows two men with a 1950s computer the size of a modern refrigerator.

Nowadays, however, a computer is just another item stocked in supermarkets alongside toothpaste and dog food. And as computers have become cheaper and smaller, they have been incorporated into a kaleidoscopic range of devices that bear no resemblance to what was once thought of as a computer. Powerful computers now sit at the heart of objects as diverse as mobile phones and games consoles, cars and vacuum cleaners. The cost of computer power continues to decrease, making it possible to incorporate computer technologies into almost any object, no matter how small, cheap or disposable. And these smart devices are ‘talking’ to one another, not just within a single room or building but across the world via the internet, using the World Wide Web (see Box 1). Thus even as the computer vanishes from sight, it becomes vastly more powerful and ever-present – to use a term you’ll become very familiar with, it is now ubiquitous.

Activity 1(exploratory)

Can you think of another technology that has made the transition from novel to commonplace, like telephones and computers?

Comment

There are many possible answers to this question. I thought of washing machines, which have advanced from hand-driven drums to the automatic machines of today.

Box 1The Internet and the Web

You may well have across the terms internet and Web. Although in everyday life people tend to use these terms interchangeably, in reality they are two separate (though related) entities.

The internet is a global network of networks: an internetwork (hence its name). It is the infrastructure that connects computers together. At first written with an upper-case ‘I’, it is increasingly seen with a lower-case ‘i’.

The Web (short for World Wide Web), on the other hand, is a service that links files across computers, allowing us to access and share information. Thus the Web is a software system that has been built upon the hardware of the internet.

Apart from anything else, this means that it is technically incorrect to refer to ‘searching’ or ‘browsing’ the internet. When you carry out an online search, you are in fact searching the Web!

1.3 The information society

Networks and the internet

As a result of advances in information and communication technology (ICT), our notions of time and location are changing – distance is no longer a barrier to commercial or social contact for those of us connected to suitable networks. Some people may find it difficult to imagine not having access to the information and services that play a crucial part in their daily lives. Others may feel that they have no part to play in the digital world because their network access is very limited or even non-existent. Some simply don’t care about the digital world, viewing it perhaps as a waste of time. Yet whether we are aware of it or not, digital information is flowing constantly around us.

Consider a computer that is connected to the internet – the one you are using to study this unit, for example. This may be a computer you use at home, in a library or at work; you may use it on the move or in a fixed location. Whatever the case, this computer is part of a complex system consisting of wires and optical fibres, microwaves and lasers, switches and satellites, that encompasses almost every part of the world. The oceans are wrapped in more than a quarter of a million miles of fibre-optic cable with several strands of glass running through it. Each of these strands can carry thousands of simultaneous telephone conversations, a few dozen television channels, or any of a range of other forms of digital content (such as web pages).

This modern communications network enables us to use a mobile phone in the depths of Siberia or take a satellite telephone to the Antarctic (Figure 3), watch television in the middle of the Atlantic, do our banking from an airliner, or play games with a person on the other side of the world. It is one of the greatest technological achievements of the last thirty years and it is so reliable, so omnipresent, that we very rarely stop to think about what actually happens when we dial a telephone number, click on a web link or switch TV channels. Or rather, we tend not to think about it until something disrupts the network – whether it be a widespread problem such as a power cut, or something more localized such as finding ourselves in a rural area with no mobile phone signal.

This colour photograph shows a man using a satellite phone while surrounded by penguins, suggesting he is in the Antarctic.

The end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century are often compared to other historical periods of great change, such as the Industrial Revolution, because of the huge technological changes that are happening in many areas of our lives. These developments are taking place in conjunction with correspondingly large social and economic changes, often characterised by the terms information society and network society. Such notions are frequently referred to by policy makers when driving forward changes in our technological infrastructure: politicians often refer to the inevitability of technological change in our information society and stress the need to be at the forefront of these changes in order to secure future prosperity, for example by developing broadband network infrastructure, by making public services available online, and by equipping schools and local communities with computers.

Activity 2 (exploratory)

Can you think of an example where changes in technology have resulted in changes to your work, social or family life? Have those changes improved your life? Have they created any problems?

Comment

The biggest change for me has been in my ability to work from home. I’m currently sitting at home typing this text on a computer whilst listening to some jazz music, which is also stored on the computer. I’ll shortly email my document to a colleague, who will be able to read it a few seconds later.

My first job required me to travel to my employer’s premises every day and share an office – and a single telephone – with ten other people. When I needed to write a report I would do it with a pen and paper for someone else to type up. A few days later I’d get it back to check and the typist would make any corrections with something called ‘correcting fluid’.

Being able to work from home has improved my life considerably. Not only does it save me the time and money that used to be spent on travelling, but being able to listen to music while I work helps me concentrate, as well as making the job more enjoyable. On the down side, the boundaries between my home life and my work life have become very blurred, as my wife will confirm. So on the whole I feel the changes are positive, but there are some disadvantages as well.

The rise of texting

Unintended uses sometimes develop alongside the intended uses of emerging technologies in our information society. A classic example is the text messaging facility on mobile phones, often referred to as SMS (which stands for short message service). This was originally a minor feature designed to be used by engineers testing equipment – it was not expected to be used by phone owners at all. Yet by 2006, mobile phone companies were earning more than 80 billion US dollars per year worldwide from SMS messages, making them one of the most profitable parts of their business (International Telecommunication Union, 2006).

SMS resulted in a whole new method of communication and form of popular culture, different ways of interacting with radio and television, and even a new language form: texting. Texting often plays a key role in arranging demonstrations against those in power. You will probably remember such events from recent news stories.

Some more figures might help to put the increase in texting into context. The Mobile Data Association gathers statistics on mobile phone usage in the UK. Their report for May 2008 (Text.it, 2008) shows that in the whole of that month:

- 16.5 million people accessed the internet from their mobile phones

- 6.5 billion SMS (text) messages were sent

- both of these figures showed a considerable increase from previous years.

In December 2008, the equivalent figures were 17.4 million and 7.7 billion respectively. In the following activity you will calculate just how large the increase in text messaging between May and December was.

‘Billion’ is a word that in the past had different meanings in the UK and the USA. However, the two countries now agree that a billion is one thousand million (1000 000 000).

Activity 3 (self-assessment)

The number of text messages sent per month in the UK grew from 6.5 billion in May 2008 to 7.7 billion in December 2008. What was the percentage growth over those seven months? You will probably need to use a calculator for this activity.

Comment

The increase in the number of messages was: 7.7 billion − 6.5 billion = 1.2 billion.

The percentage growth is found by dividing the change (1.2 billion) by the starting number (6.5 billion) and multiplying the answer by 100%. This gives: growth = 1.2/6.5 × 100% = 18.5% in seven months.

1.4 Section summary

In this section, having briefly considered the rapid development of computers, I outlined some of the ways in which digital technologies pervade the world around us, giving rise to the social and economic changes that characterise our information society. The concept of an information society is a key one in this unit and in the next section I’ll try to give you a better idea of what it involves.

2 Some aspects of our information society

[Timings. This is the second section of this unit. It should take you around three hours to complete. If you don’t have time to work through it all at once, there are break points where you can stop and return later.] In the previous section I introduced the concept of an information society; in this section I will outline some key aspects of such a society.

The changeable nature of the online world

One of the things you will notice while studying this unit is that some of the examples you read about no longer exist, or are nothing like as important as when the material was written in 2010 and 2011. This is inevitable, and you shouldn’t be concerned by it; your focus should be on the general principles, which remain valid.

As an example, there was a time when if you wanted to find something online you didn’t go to Google, because that didn’t exist. Instead, you almost certainly went to a search engine called AltaVista. I’ve just checked and this currently still exists at http://www.altavista.com, but it is now owned by Yahoo! and looks very similar to Google. However, back in the late 1990s it was seen as the definition of what a community portal site should be, combining a search function with links to a range of information sources; as a result, it was the first-choice search engine for many people. It continued to develop, and was one of the first to allow users to search for images and to translate text from one language to another. However, by late 2001 Google had overtaken AltaVista in both popularity and ease of use, and we’ve now reached the stage where relatively few internet users use or even know about AltaVista.

Some companies you read about may no longer exist, and some may be more or less prominent. Yet the likelihood is that although companies come and go, there will still be ways to share photos (as Flickr and Picasa allow at the moment), to edit documents online (as is possible with Microsoft Office Live and Google Drive), to store files online (as Dropbox and Ubuntu One allow), and so on.

2.1 Business

Financial services

Every time you use a debit or credit card in a shop, the shop till communicates with a card terminal that transmits your identification details from your card to your bank or credit card company for verification. Your balance is then adjusted according to your purchase. A similar chain of events is initiated if you shop online (buying a ticket for an airline or train, perhaps) or over the phone (when booking a cinema ticket, for example). Many banks also provide online banking services, reducing the need for customers to visit a branch. Automated teller machines (ATM) allow you to check your bank balance and withdraw cash wherever you are in the world. In each of the above situations – using a debit or credit card, shopping or managing your money online or over the phone, or using an ATM – the machines involved are connected via a network to a central computer, which has records of your account in an electronic filing system known as a database.

Financial services have undergone huge changes in recent years as a result of developments in the digital technologies driving them. The examples just described show how convenient and accessible such services have become. Yet at the same time, issues of identity and security have become a concern. New ways of communicating have also created new types of crime, including identity theft and financial fraud. In turn, these problems have fostered the development of new security industries that try to inform us and sell us solutions to reduce the chances of us becoming victims of online crime.

Commerce

Advances in digital technologies have led to changes in many areas of commerce, with some existing kinds of business being transformed by the opportunities these developments offer. One of the most obvious changes is the emergence of retailers such as Amazon, which have an online shop but no physical one that customers can visit. Yet the internet not only benefits the largest companies, but also allows even the smallest retailers to advertise their services to a global audience. Incredibly specialized companies can flourish by relying on the internet’s immense reach to deliver potential customers.

Of course, this growth has resulted in casualties in traditional (sometimes called ‘bricks and mortar’) retailing. High-street shops specialising in items such as books, DVDs, music and games have all lost business to online retailers. This has driven some shops out of business, but a number of high-street stores have also opened successful online stores. Online retailers have lower costs – they don’t pay expensive high-street rents and can easily be based in countries with low tax regimes – and they can pass these savings on to customers.

Although the low costs offered by online stores can be very attractive to customers, they might be counterbalanced to some extent by the less immediate and less tangible nature of the shopping experience. However, online retailers make up for this by providing a variety of services that reassure and inform their customers. One such service is the tracking of goods online – though this is a development that can produce its own frustrations, as illustrated by the cartoon in Figure 4. Having bought a new computer a few years ago and tracked it on its way from the factory in China to my home, I can identify with the feeling expressed!

This cartoon is titled ‘Online Package Tracking’ with a column of Pros and another of Cons. The Pros are ‘convenient’ and ‘useful’. The Cons are ‘makes you crazy’. The cartoon shows a person sitting at a computer, pressing ‘refresh’ repeatedly and each time saying ‘Aww, still in Memphis’.

Activity 4 (exploratory)

Add some more entries to the following table of advantages and disadvantages of online shopping. Can you think of ways in which online retailers may try to address the disadvantages?

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Buyer |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

| Seller |

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

To use this interactive functionality a free OU account is required. Sign in or register.

|

Comment

I thought of the following, but you may have come up with others.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Buyer | More choice | Can’t try goods (e.g. shoes, clothes) first |

| Can often track goods | Harder to return goods if faulty | |

| Often cheaper than a local shop | Harder to get help and advice before or after buying | |

| Some items can be downloaded immediately after buying | May be worried about online fraud | |

| Seller | No need for a physical shop | Reliant on delivery services |

| Lower running costs | Likely to get more returned goods | |

| Don’t need to keep everything in stock – can arrange delivery from suppliers | Need to respond to email or telephone queries | |

| Can supply music, books, software, etc. for download rather than having to supply a physical item | Some potential customers reluctant to buy online |

Online retailers may try to address the disadvantages listed above in various ways. For instance, they might provide:

- free collection of returned items

- links to online reviews of products to help advise prospective buyers

- telephone helplines

- support forums to help customers before and after buying

- advice on how to shop safely online.

As well as direct retailing, other types of businesses have also moved online – auction sites such as eBay fall into this category. Some online businesses are less conventional, and as a result it’s often harder to see how they find the money they need to survive. For example, there are many collaborative projects that produce free products including software, online encyclopaedias and educational resources. These often rely on volunteers contributing their time, with money being provided by advertising, sponsorship or donations.

Work

Technology has changed the way that other businesses operate too. Greater quantities of information are exchanged between numerous locations over public and private networks. Vast amounts of data are stored on computers and accessed remotely from a variety of devices. Just as individuals buy from companies online, many companies now sell to each other online as well, for the same reasons of reduced cost and wider choice that attract individuals to online stores. Manufacturing tasks that used to take days can now be completed in minutes using computer-operated machine tools working in automated production lines.

The way we use technology has also affected our individual working lives. For example, telephone and online banking mean that banks no longer need large numbers of counter staff, and the role of travel agents has changed as more people book their holidays directly from the vendor by going online. Some companies have responded by reducing their number of employees, while others have retrained their staff to provide more specialised services to their customers. More generally, many people working in an office environment are expected to learn how to use new software applications in order to do their jobs.

2.2 Communities

[Break point. This would be a good point to take a break if you need to do something else before returning later.] As well as revolutionising the commercial world, the internet has had an enormous impact on the way we communicate. While there are still people in many parts of the world who do not have internet access, many of us have access at home or at work. As a result we have the opportunity to communicate with others using email, instant messaging and online discussion groups (in online forums). Existing communities have created new ways of communicating, and new online communities have developed. Social networking plays an increasingly significant role in the lives of many people.

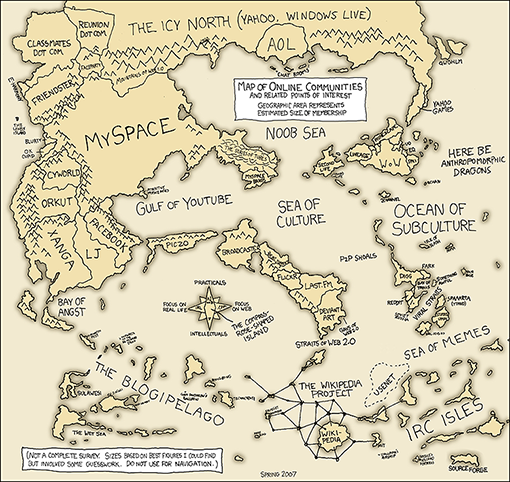

The recent pace of communication change has amazed many of us, and there is no reason to think things will slow down. The cartoon map of online communities shown in Figure 5 appeared on the Web in early 2007. Since then, the social networking site Facebook has increased in significance and size at the expense of MySpace, and micro-blogging sites such as Twitter – which allows users to post and read short messages – have appeared and grown.

This is a hand-drawn map with imaginary continents and islands labelled with the names of online communities. It is entitled ‘Map of Online Communities and Related Points of Interest: geographic area represents estimated size of membership’. MySpace is the most prominent area of the map, surrounded by a variety of other social networking sites, of which Facebook is one of the smallest. There is an online gaming area including World of Warcraft and Second Life, and an entertainment area including Flickr and Last.fm.

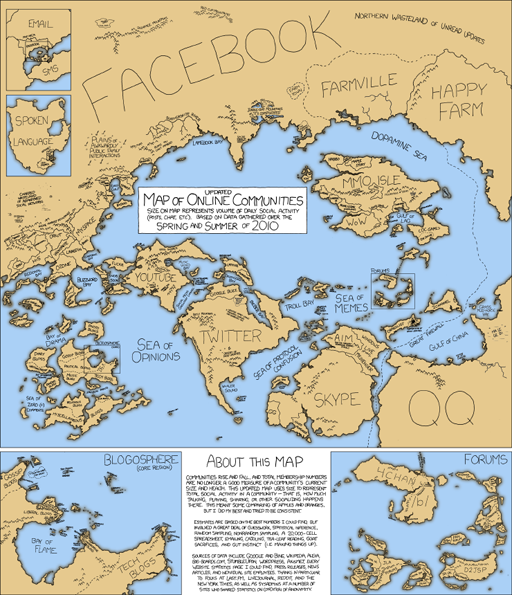

An updated version of this map is given below. It gives a feel for those changes and more.

This is a similar map to the one above, entitled ‘Updated Map of Online Communities: size on map represents volume of daily social activity (posts, chat, etc) based on data gathered over the spring and summer of 2010’. A note points out that ‘Communities rise and fall, and total membership numbers are no logner a good measure of a community’s current size and health’. The map itself is more complicated than the 2007 version, with insets for blogs and forums. Facebook has grown a huge amount, while MySpace has shrunk. YouTube is about the size that it was before, but there are several prominent new areas including Twitter, Skype and QQ.

2.3 Information

The internet has had a huge impact on the availability of information of all kinds. Material on the Web reflects widely differing viewpoints, from official news bulletins to unofficial rumours, and comes from widely differing sources, from commercial megastores to community groups. Since no individual government, company or person has control over it, the internet has paved the way to unfettered publishing of information of all kinds, raising questions about the authority and regulation of this information. Some governments try to exert control over the information their citizens can access and create, with varying degrees of success.

2.4 Entertainment

The world of entertainment is constantly evolving as new ways of creating and distributing the media we watch and listen to are developed. Digital broadcasting has changed the way we experience television and radio, with increasingly interactive and participative programmes. Digital cameras, printers and scanners, together with desktop publishing and photo-editing software, enable greater numbers of people to experiment with image production, while online image- and video-sharing sites allow anyone with access to a relatively basic mobile phone or digital camera to share photos and videos with the rest of the online world. New digital technologies have also been at the forefront of changes in the production and distribution of music, and computer gaming has developed hand in hand with the evolution of graphical interfaces.

However, our increased exposure to digital entertainment has resulted in increased conflict between the rights of the consumer and the rights of the producer of the media. It is now much easier for the products of the media industries established during the twentieth century – film, music and so on – to be illegally copied and distributed in a form that is indistinguishable from the original. Copyright holders are taking steps to prevent this by developing a range of digital rights management (DRM) techniques that make it much harder to create copies, as well as by trying to persuade users of the benefits of the original product. Such attempts at persuasion can look very threatening, as I noticed on a recently purchased CD that has the following printed on the back cover:

FBI Anti-piracy Warning:

Unauthorized copying is punishable under federal law.

Several questions came to mind when I read this. Does that mean I can’t legally put the music onto my MP3 player? Can the US Federal Bureau of Investigation extradite and punish me (a UK citizen who bought the CD in the UK) if I do? Should I return the CD to the place I bought it from and ask for my money back? Or will I be in trouble only if I distribute copies of the CD to other people? These are all valid concerns that demonstrate some of the problems surrounding the use of copyrighted material.

There are many other issues arising from this, and it is very easy to make the digital future sound bleak. You have probably heard predictions to the effect that illegally copied media, and making information freely available on the Web, will increasingly put whole businesses and hundreds of thousands of jobs in the established media industries at risk. However, as in other areas of the digital world, there are also opportunities for these businesses if they can adapt to the new environment and modify their business models to survive and grow in different directions.

Activity 5 (exploratory)

Can you think of any other problems connected with the growth of digital entertainment?

Comment

There are many possibilities. I thought of the fact that the advent of digital television affected even those who didn’t particularly welcome it – across the world, analogue signals are gradually being switched off as new digital signals are introduced. In time, everyone will have to get new digital televisions as the old analogue versions become obsolete – quite an expensive business!

You might also have thought of more technical problems, such as how to transmit the large quantities of digital data required for some forms of entertainment – video, for example – in an acceptable time and retaining acceptable quality.

2.5 Public services

Public information and services

Public bodies such as governments and transport agencies are increasingly providing services online, allowing us to organise various aspects of our daily lives more easily. These services range from simple information displays, which let us check things such as weather forecasts and transport timetables, to interactive sites that allow us to make bookings or queries.

In many parts of the world, medical records are increasingly moving away from paper and X-ray film towards becoming completely digital. This has several advantages, especially in allowing patient records to be easily shared between departments within a hospital, and sometimes more widely with doctors’ surgeries and other health workers. In remote rural areas of some countries, doctors can make use of computer networks or even mobile phones to make a diagnosis if they are unable to see the patient in person. However, this is by no means universal, and even where such facilities exist they aren’t always available.

Information for travellers is also increasingly being made available digitally: for example, live online updates on road congestion and public transport, and arrivals information in stations and airports. Similarly, it is becoming more and more common to book plane journeys online – in fact, some airlines now only accept online bookings and will only issue electronic tickets. Many of them strongly encourage, or even require, passengers to check in online as well.

In addition, many countries provide online access to at least some of their government services. For example, you might be able to renew or apply for a passport, book a driving test, claim benefits, or fill in your tax return online. Local authorities also provide digital information services – you might be able to reserve or renew a library book online, for instance – and there are numerous opportunities to learn online.

Security and risk

The twentieth century saw a dramatic change in the role of the state in many countries. During most of the nineteenth century, an individual might only have come into contact with the state for the purposes of taxation, marriage and death; at the end of that century and the beginning of the next, however, a series of social revolutions saw the state becoming involved in our healthcare, pensions and education. Unsurprisingly, each of these developments was accompanied by a significant increase in the amount of personal information stored about every one of us. Computer technologies were developed especially to serve the enormous projects involved; IBM became a highly successful company due to its work on censuses in the USA and Europe, whilst the world’s first business computer, LEO, was used for a variety of tasks including the calculation of tax tables for the British Treasury in the 1950s.

With the vast amount of personal information being held about us in various places, it is becoming increasingly important for us to be able to prove our identities – not just for travel but for other activities such as purchasing expensive or restricted items, paying bills and opening bank accounts. The UK is unusual in Europe in that (at the time of writing in 2010) it does not have a compulsory identity card system, despite the fact that identity cards were put in place during both world wars. In several countries, identity card or passport schemes are being upgraded with new biometric technologies such as iris or face recognition, which (perhaps rather over-ambitiously) promise to uniquely identify individuals.

As well as the personal information that we know about, there may also exist information about us of which we are unaware. Since the terrorist attacks on the USA in 2001, much of the Western world has become far more security conscious, and governments and companies alike have developed and deployed technological countermeasures. These range from smart video surveillance systems that can identify an individual in a crowd and track his or her movements, through the biometric technologies mentioned above, to the searching of databases for suspicious activity.

Activity 6 (exploratory)

Can you recall an occasion when you have been personally aware of technological security measures?

Comment

On a recent visit to the USA I went through a range of airport security screenings. In addition to having my belongings checked, I was photographed at least twice (as well as being under almost constant video surveillance in the airports), had my fingerprints scanned electronically, and was required to fill in numerous online and paper forms.

The promise is that such technologies will make us safer, but could they turn the world we live in into a society strangely reminiscent of the nightmare vision contained in George Orwell’s novel 1984?

As you’ve seen so far in this section, there is plenty of opportunity for digital information about each of us to be created. Some of this information we might intentionally give out ourselves – on social networking sites, for example. Other information about us may, as described above, be gathered more surreptitiously by various agencies. In general we have little control over how digital information about us is used or who receives it. We might assume that information gathered legally by a government agency, for instance, will be handled appropriately and used only for our benefit; yet there have been many examples of governments and private organisations ‘losing’ confidential data by transferring it insecurely. For example, in November 2008 the UK government announced that two CDs containing personal information about 25 million people had been lost by HM Revenue and Customs when they were posted to the National Audit Office. If criminals got hold of such information then there would be the risk of our identity or our money being stolen.

2.6 Communicating on the move

Advances in digital technology have, in a very short space of time, revolutionised the way many of us live our lives. Nowhere is this more evident than in our ability to communicate as we travel. Below I’ll share with you a personal example that highlights some of the changes, and some of the opportunities and problems these changes have created.

In the 1980s my employers of the time set up an email account for me with a commercial email provider called CompuServe. This required me to use a modem to connect my computer to a telephone line and dial one of a set of specific phone numbers so that my email could be transmitted. This was fine if I was in the office, but more complicated when travelling as very few hotels made telephone sockets available to customers. As a result, my travelling kit soon contained a selection of small screwdrivers for dismantling hotel telephones, and a set of wires, crocodile clips and pliers so I could wire directly into the phone system. Of course, this was all done at my own risk and without the knowledge or approval of the hotels, and I am not recommending it!

In those days, even when I did manage to get online, email transmission was very slow and expensive. Nowadays I have a mobile phone with which I can send and pick up emails quickly and cheaply wherever I am (without the need to dismantle a fixed-line telephone!). As well as email, my phone enables me to communicate in several other ways – instant messaging and social networking, for example, not to mention voice calls. I can also use the built-in global positioning system (GPS) to find out where I am, and even plot my location on a website to let my friends and family see where I am (or at least see where my phone is).

This last feature was very useful when my wife and I tried to find our son’s new flat for the first time, as the last mile of the journey was rather more complicated than expected. Our son could check online and see exactly where we were, and he could also talk to us and guide us to the right place. Yet a service like this also has some disadvantages – most importantly, I need to remember to turn it off if I don’t want people to know where I am. A few months later, I realised on returning home after buying my wife a birthday present that the same service will have showed that I spent 20 minutes in a jeweller’s shop. I don’t think she noticed, or if she did she didn’t allow it to spoil the surprise. However, it’s not hard to imagine other circumstances in which I might not want my location to be publicised, even to my family and friends (Figure 7).

This is a cartoon showing a woman using a laptop and talking to a friend. She is saying ‘I’m tracking my husband through his GPS unit. Right now, he’s between a televised sporting event and the refrigerator.’

2.7 Section summary

In this section you’ve learned about some of the key aspects of an information society, online social networking being one of them. In the next section I’ll outline some ways in which you can participate in online discussions effectively.

3 Participating in a digital world

[Timings. This is the third section of this unit. It should take you around two hours to complete. If you don’t have time to work through it all at once, there are break points where you can stop and return later.] Previously in this unit I’ve mentioned the rise of social networking – one aspect of our increasingly digital world. You may already communicate online to some extent in your daily life.

What follows in this section is a quick guide to good practice in contributing to online discussions. It should help you to work and socialise with others online – in your studies, your social life and your working life. Much of the content is summed up by the familiar tenet known as the Golden Rule: a concept common to many ethical codes, which simply states that we should treat others as we would want them to treat us. Just as this Golden Rule is relevant to good manners – ‘etiquette’ – when talking face to face, so it is relevant to online communication. To help us apply it, it has been developed into guidelines for online behaviour called ‘net etiquette’ or, more commonly, just netiquette.

Netiquette is intended to make us all think about how we behave online and to make us aware of the effect our words could have on others reading them. If it seems that there are far too many rules to follow, be reassured that they aren’t hard and fast commands that you must remember and obey. Netiquette does not encompass every situation you may find yourself in – it’s perfectly possible to obey all the guidance below and still annoy someone – but it will give you a good foundation for your participation in online discussions.

Most of what follows is common sense and good manners. Some of it may be familiar to you, but please take time to read it if you don’t have much experience of using online discussion groups to work with others. There’s a big difference between working in an online community and socialising online, so even if you are experienced at the latter, you should find the following material useful.

3.1 Netiquette: Respecting others online

As children we quickly learn many rules about how to interact with other people. Some of these rules are common sense, such as ‘don’t interrupt a speaker’ and ‘say please and thank you’, and are necessary if we are to reduce the likelihood of arguments or causing offence.

When we have a face-to-face conversation, we don’t just rely on the spoken words to establish the other person’s meaning; unconsciously we are also monitoring the tone of their voice, their facial expression and their body language. Telephone conversations are a little more ambiguous because we can no longer see the other person; email and online discussions are harder again, since all we have is text. It is extremely easy to misinterpret words on a page, so the writer must take great care before pressing the button that sends their message to the world.

Thank, acknowledge and support people

People can’t see you nod, smile or frown as you read their messages. If they get no response, they may feel ignored and be discouraged from contributing further. Why not send a short reply to keep the conversation going? This can make a big difference in a small group setting. However, do bear in mind that in a large, busy forum too many messages like this could be a nuisance.

Acknowledge before differing

Before you disagree with someone, try to summarise the other person’s point in your own words. Then they know you are trying to understand them and will be more likely to take your view seriously. Otherwise, you risk talking at each other rather than to each other. You should also recognise that other people are entitled to their point of view, even if you consider them to be entirely wrong.

Make clear your perspective

Try to speak personally. That means avoiding statements like ‘This is the way it is …’ or ‘It is a fact that …’. These sound dogmatic and leave no room for anyone else’s perspective. Why not start by saying ‘I think …’ or ‘I feel …’? If you are presenting someone else’s views then say so, perhaps by using a quotation and acknowledgement.

Emotions

Emotions can be easily misunderstood when you can’t see faces or body language. People may not realise you are joking, and irony and satire are easily missed – all good reasons to think before you send a message. To compensate for these restrictions, early internet users came up with the idea of the smiley face – :) or :-) – which then grew into a whole family of emoticons.

Remember that the systems upon which many forums are based only support plain text, so you can’t always rely on fonts and colours to add meaning. Even if you are using a forum that allows so-called ‘rich text’, it’s possible that other users will be picking up messages as plain text emails or as text message alerts on their mobile phones and will not see your formatting. AND DON’T WRITE IN CAPITAL LETTERS – IT WILL COME OVER AS SHOUTING!

If you read something that offends or upsets you, it is very tempting to dash off a reply immediately. However, messages written in the heat of the moment can often cause offence themselves. It’s much better to save your message as a draft and take a break or sleep on it. That gives you a chance to come back to your message when you’re feeling calmer and ask yourself ‘how would I feel if someone sent that message to me?’. If you decide it will make things worse then make sure you edit it before you send it.

The best advice is to try to be aware of your audience before you post. The internet is a global phenomenon; people from widely differing cultures and backgrounds may read what you write online, and what you find funny may be offensive to them. It may take time to work out what sort of ‘audience’ can be found in a particular forum; some are very permissive and allow almost any sort of behaviour, while most (like those at The Open University) will not tolerate bad behaviour or abuse.

Activity 7 (exploratory)

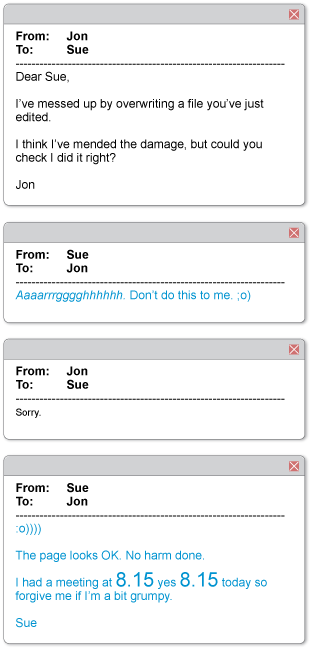

Look at the email exchange shown in Figure 8. What emotions are being expressed through smileys and typography? Would Jon and Sue still be on speaking terms if they hadn’t used these devices?

This is a series of four email messages between Jon and Sue.

Message 1 says ‘Dear Sue, I’ve messed up by overwriting a file you’ve just edited. I think I’ve mended the damage, but could you check I did it right? Jon’.

Message 2 is from Sue and says ‘Aaaarrrgggghhhhhh. Don’t do this to me. ;o)’. The ‘Aaaarrrgggghhhhhh’ is in italic font. When viewed on their side the final three characters, ;o), look like a face that is smiling and winking.

Message 3 is from Jon and says ‘Sorry’ in a smaller font.

Message 4 is from Sue and says ‘:o)))) The page looks OK. No harm done. I had a meeting at 8:15 yes 8:15 today so forgive me if I’m a bit grumpy. Sue’. When viewed on their side the first set of characters, :o)))), look like a smiling face with lots of extra smiles. The text ‘8:15’ is shown in a larger font both times.

Comment

In Sue’s first reply to Jon she expresses her frustration by typing ‘Aaaarrrgggghhhhhh’, but she ends that message with a winking smiley. Jon’s reply then says ‘sorry’ in a very small voice! Sue’s final reply starts with a happy smiley to show that everything’s OK. She uses a large font when she mentions the annoyingly early meeting time.

I feel sure that Jon and Sue would still be friendly after this email exchange. But I have seen email exchanges between colleagues that had the opposite effect, when the participants didn’t take care about how they expressed themselves in their messages.

Moderation

Moderators are forum participants responsible for keeping order. They may have capabilities within the forum greater than those of other participants; for example, they can sometimes add new participants and suspend people who are abusive. They also work to keep the discussions friendly and relevant to the forum. A forum with a moderator is said to be moderated. Forums without moderators are unmoderated and are generally places where newcomers should tread very carefully. Moderators tend to introduce themselves early on in forum discussions, so it’s usually clear whether a forum is moderated or not.

Some other advice

- Keep to the subject, and pick the right forum for your contribution.

- Before you write a message, check any rules about what is and is not considered acceptable in the forum. Many discussion forums have rules, aside from netiquette, about things such as links to commercial sites.

- Take a little time to use the forum’s search facilities to see if your question or topic has already been discussed or covered in a set of frequently asked questions (FAQs). If it has, you should at least scan the existing messages to see if your points have been addressed.

- Don’t feel you have to post immediately. Take your time to see what is being discussed and get a feel for the group you’re joining. This very sensible behaviour has the unfortunate name of lurking but is quite acceptable online. If you want to post, many discussion groups have a forum devoted to new users where they can introduce themselves to other readers. These are always good places to get started.

- Try to keep your messages short and to the point. People don’t want to read long, rambling messages, especially if they can’t work out what response you’re looking for.

- Write a concise subject line (title) for your message – people often won’t spend time reading messages unless the subject line looks relevant.

- Keep to one subject (topic of discussion) per message. If you want to cover another subject, do it in another message.

- When replying to a message, quoting part of that earlier message can be helpful so that readers can easily see what you are referring to. Add your response after the quoted material, not before it. And keep your quotation short and to the point, otherwise the resulting messages will get longer and longer.

- If you ask a question and it is answered, thank the person who responded. It’s not only polite, it also shows that the discussion has come to an end.

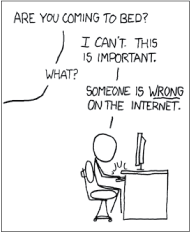

- If you’ve reached a point where you disagree with someone and neither of you is going to change your opinion (Figure 9), realise the conversation is over, agree to disagree, and move on.

This is a cartoon showing someone at a desk, typing on a computer while talking to someone else off-screen. They are asked ‘Are you coming to bed?’ and reply ‘I can’t. This is important.’ When asked ‘What?’ they reply ‘Someone is WRONG on the internet.’

Activity 8 (exploratory)

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

3.2 Ethical and legal considerations

[Break point. This would be a good point to take a break if you need to do something else before returning later.] In using a computer for communications you have many rights of free expression, but you also have certain responsibilities to respect others and to have some awareness of privacy and confidentiality in relation to online communications. You should be aware of the following points:

- An email is generally considered to be equivalent to a private letter, and should not be quoted or forwarded to anyone else without the permission of the original sender. This can be particularly poorly observed in companies (even those whose employees are told to assume that all online communications are for the recipient’s eyes only, unless otherwise stated).

- Besides the informal rules of netiquette, most forums have a code of conduct and conditions of use that govern acceptable behaviour. For example, the use of the online forums provided by The Open University is covered by its Computing Code of Conduct. You will usually find a forum’s terms of use linked from its home page, or listed in the code of conduct that you are asked to agree to when you first register for an account.

- Considerations of copyright and plagiarism (cheating by using another person’s work as if it were your own) apply to online discussions. If you are quoting something written by someone else, put it in quotation marks and acknowledge the source.

- Some forums are not wholly public, in which case messages should not be copied outside the forum. The forum’s terms of use may specify this.

3.3 Copyright

One of the reasons the Web has grown so quickly, and one of its most fascinating aspects, is that almost anyone can publish almost anything on it. It is very easy to find information, images, audio and video files on the Web, which you can then save and incorporate into your own material.

Copying is so easy that people often make the mistake of assuming that everything on the Web is freely available. This is not the case: most information you will come across is likely to be covered by copyright law. This applies not only to online television programmes, music, photographs, books and so on, but also to information – for example, in the form of online academic papers or simply in someone’s blog.

Material not subject to copyright is said to belong in the public domain and can be used by anyone. Older works of art and literature, such as the works of Shakespeare and Beethoven, are in the public domain. However, individual printings, adaptations or recordings of those works are copyrighted to the publisher or performer. The situation can become very complicated because the duration and extent of copyright differs between countries. For example, material may be in the public domain in the USA but still under copyright in the UK. As a result, it is always wise to assume that any third-party material (that is, material originating from someone else) is still protected by copyright unless you’re sure it’s in the public domain.

Copyright holders can prosecute individuals and organisations for infringing their rights; in recent years, music and film companies have sued individuals for very large sums of money. Below are some general points you should bear in mind.

- You should seek the author’s permission if you wish to use any copyrighted material. Just because something is on the Web does not mean it is freely available for you to use.

- Many websites have usage policies explaining how their material can be used. Some are more restrictive than others, so make sure you find and follow the relevant policies.

- Information published online may have been put there by someone who is not the copyright holder.

- When quoting text in your own academic work (other than in assignment answers – see below), the generally accepted guideline from copyright legislation is that you can use a whole chapter or up to 5% of any one book without seeking permission, but you must give a full reference to show where it has come from.

This may all seem rather intimidating, but it’s not quite as bad as you might fear – fortunately, copyright law makes some concessions to students. As a result, you don’t have to ask permission to use copyrighted material in answering an assignment question, although you must still include references. However, if you want to reuse the same material for any other purpose at a later date, normal copyright law applies and you must seek permission.

3.4 Good academic practice

Many courses will encourage students to use the Web as a resource. Students use it as part of their studies and in their assignments, and they should find it a great help in understanding and practising the things they learn.

However, using information found on the Web in this way can cause problems unless you take a little care. When using material written by other people you can quote their words, but good academic practice is that such quotations should always be limited and acknowledged. This applies whether you’re quoting from this unit or from other sources such as websites, journals or newspapers.

It can be very tempting to copy and paste large chunks of text into your notes – and possibly then into assignment answers – without giving a reference. However, that is very bad academic practice. It’s far better to use quotations sparingly and to rewrite most of the material in your own words. This allows you to show that you’ve understood the material and it also helps you to remember it.

In addition, it’s good academic practice to give a reference to the source of any third-party material you include in your own work. Not doing so is not only impolite, as you’re failing to acknowledge the help that someone else’s work has given you; it’s regarded as plagiarism and is never acceptable.

To help students, university websites often provide a guide on how to reference sources of information correctly, including those you might find online.

3.5 Section summary

In this section I’ve discussed some of the ways in which you can make good use of the Web, both for interacting with other people and for finding information. When working online it is also important to consider how to protect yourself and your computer, and that’s what I’ll turn to next.

4 Online safety

[Timings. This is the fourth section of this unit. It should take you around two hours to complete. If you don’t have time to work through it all at once, there are break points where you can stop and return later.] The internet provides many ways for people to get in touch with each other, but this ease of contact can have downsides for the unwary. It can expose internet users to the dangers of malicious software, to unsolicited and nuisance emails, and to a variety of hoaxes. In this section I’ll describe some of these problems and suggest how you can protect yourself from them.

4.1 Malware

Software designed to cause damage is known as malware. There are several types of malware, three of which are described below. However, be aware that as malware evolves to avoid detection, the boundaries between the different categories are tending to blur.

The best-known type of malware is probably the virus. This is a piece of software that has been written to attack software on your computer, often with the specific intention of causing harm – deleting files, for example. A virus attaches itself to other software on your computer and activates when that software is run. Viruses are so called because they are designed to spread quickly and easily from one computer to another via internet connections or external storage devices such as memory sticks.

Another type of malware is the worm. This is a piece of malicious software that runs ‘in the background’, doing some damage to your computer even though you may not realise it is running. Worms can make copies of themselves, and those copies can spread via an internet connection. A worm typically consumes resources by running on a computer; in a major attack, all of a computer’s processing resources could be used in running the worm and its copies.

Finally, the trojan is a digital equivalent of the legendary wooden horse that smuggled Greek soldiers into Troy. It appears to be legitimate software, such as a screensaver, but behind the scenes it is causing damage – perhaps allowing someone else to gain control of the computer, copying personal information, deleting information, or using email software to pass itself on to other computers.

Protecting your computer

There are three main ways to protect your computer against malware.

- Ensure that your computer has the latest patch from the producer of your operating system (OS). Microsoft, Apple and other producers frequently issue patches for their products.

- Make sure other software is kept up to date – Adobe Reader, Flash, Java and web browsers (such as Internet Explorer, Opera, Firefox, etc.) to name just a few. As new malware is discovered, so new versions of software are released that guard against it.

- Install anti-virus software and keep it up to date. Anti-virus software catches a very high percentage of malware, but only if the version on your computer is regularly updated. Remember that if you don’t use Windows, it is still possible to pass on files infected with malware to Windows users. That’s why the main job of anti-virus software for Apple’s OS X is to check files for things that could infect Windows machines.

In addition, you can use a piece of software called a firewall. This tries to stop unauthorised access to your computer without impeding your own authorised online access. There may be a firewall built into your computer’s operating system; others may be present in the hardware that connects your computer to the internet.

As well as the technical protections described above, you should protect yourself by using anti-virus software to scan any files you receive before you open them. This should include:

- files you download from the Web

- files given to you on removable media such as a CD or memory stick

- files attached to emails.

Bear in mind that no reputable software company sends unsolicited email messages with attachments, claiming to be giving you an update.

4.2 Spam

Spam is the general term for unsolicited emails sent to large numbers of people. Such emails could be hoax messages designed to mislead, or they could be used to advertise a product.

In terms of advertising, spam email is similar to the marketing leaflets and letters that drop through your letterbox at home. However, this paper mail is subject to legislation that tightly controls the range of products and services being offered. The equivalent legislation does not yet exist in the electronic world, although new laws are being introduced. For example, in the USA the federal law ‘Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing’ (CAN-SPAM) took effect in January 2004, whilst in Europe the EU ‘Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications’ came into force in the latter part of 2003. Though such national legislation is intended to limit the volume of spam email, in practice this is a very difficult task because the internet crosses national borders. Spam can be sent from one country to another, and countries that have legislation find it hard to enforce their rules in countries that do not.

Spam email can be sent only if the spammer (the person initiating the spam) has a collection of email addresses to send to. Common ways to ‘harvest’ email addresses include:

- company databases

- websites

- online discussion groups

- including links in images within emails, which when clicked by the recipient inform the spammer that the message has been opened

- infecting unprotected computers with malicious software to look for addresses.

Spammers may harvest vast numbers of email addresses, but not immediately know whether a particular email address is ‘live’ (actually in use) – it could be that the original owner of the address no longer uses it. So beware of spam emails that appear to give you the option to unsubscribe from a mailing list (very often by offering a web link to click on). If you select this option, this will verify to the spammers that your email address is live; they can then continue to send you spam, or even sell your email address to other spammers. So using the unsubscribe option can increase your spam rather than reduce it.

Below are some guidelines for minimising the spam you receive.

- Don’t reply to spam emails.

- Don’t use the unsubscribe option in response to unrequested emails.

- Don’t reveal your email address unless you want to receive mail from a particular source.

- Don’t post your email address on a website.

- Don’t use your regular email address when registering on websites or joining discussion groups. Either create a new email address for these purposes or use a spare one that you’re happy to abandon if necessary (e.g. a web-based email account such as those offered by Yahoo, Microsoft, Google, etc.).

- Set your email software to filter out unwanted messages. Most email software is equipped with ‘junk mail’ filters that can be set to identify and remove spam messages as they arrive in your inbox. Additionally, your internet service provider (ISP) may filter incoming mail for spam before it even reaches your inbox.

- Ensure that all other users of your computer follow the above guidance.

4.3 Hoaxes

[Break point. This would be a good point to take a break if you need to do something else before returning later.]A hoax message aims to mislead, often relying on the naivety of its recipients. One of the most notorious hoaxes concerned the so-called ‘Good Times virus’. This hoax is described by Sophos (n.d.), a company that develops anti-virus software, as follows. (Remember this is a hoax, so please don’t spread the news about the Good Times virus as so many others did!)

Probably the most successful virus hoax of all time, Good Times has been scaring people since 1994. It’s still going strong, despite the fact that it is completely untrue; there is no such virus, and indeed it is impossible for a virus to do what is claimed for Good Times.

The hoax started off simply: it warned people not to read or download any email with the subject of “Good Times”, because the messages were viral and would erase their hard drives. Later, more detail was added, telling of the damage that would be done to the user’s computer system.

The end of the spoof warning contained an exhortation to “Forward this to all your friends. It may help them a lot.” […] In their thousands, people did, and still do.

The secret to the success of the hoax is that it successfully taps into computer users’ fears about computers, security and the Internet, and contains pseudo-technical babble that sounds convincing.

This description indicates how convincing the message in this case was. Hoax messages can spread rapidly via email and forums, often passed on unwittingly by work colleagues, family, friends and even reputable online retailers. Unfortunately, users who fall for hoaxes can cause problems both for themselves and for others. A hoax can generate spam (when, as with Good Times, it directs the recipient to pass on the message), cause files to be deleted unnecessarily and potentially harmfully (by directing the user to delete them), and generally cause panic.

Like Sophos, most anti-virus software vendors maintain information on hoaxes on their websites, so you can check such sites if you suspect a hoax. Alternatively you can use a search engine: by searching for significant terms contained within the hoax message, you may find reports on reputable sites such as the Sophos site.

4.4 Phishing

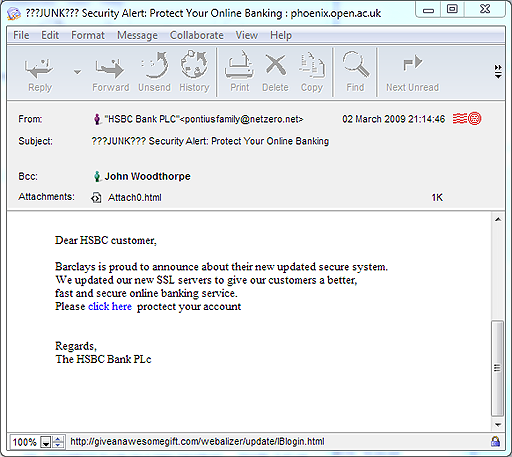

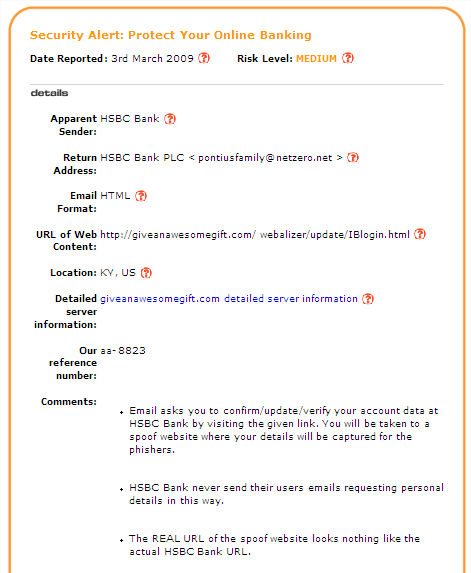

A particular kind of hoax message aims to persuade users to disclose private information such as their credit card details and PIN (Personal Identification Number). This is described as phishing. The recipient of the message may be directed to a hoax website where they are requested to part with their details. Figure 10 shows an example of an email that I received.

This is an email claiming to be from

“HSBC Bank PLC”

sent on 02 March 2009 at 21:14:46. The subject of the email is

‘Security Alert: Protect Your Online Banking’

The text of the email is

‘Dear HSBC customer, Barclays is proud to announce about their new updated secure system. We updated our new SSL servers to give our customers a better, fast and secure online banking service. Please click here proctect your account. Regards, The HSBC Bank PLc’

The text ‘click here’ is in blue to show that it is a hyperlink.

Activity 9 (exploratory)

Looking at the email in Figure 10, what warning signs are there that might alert you to the fact that this is an attempt at phishing?

Comment

Below are the warning signs I noted when I received this email.

- Although the sender’s email address is described as ‘HSBC Bank PLC’, the actual address – pontiusfamily@netzero.net – appears to have nothing whatsoever to do with the bank; instead it sounds like a private email address.

- The email address of ‘netzero.net’ refers to an internet service provider – NetZero – based in the USA. I can’t imagine that a bank based in the UK would contact me from an email address supplied by an internet service provider in another country.

- There is confusion about which bank this email is meant to be from, as the message refers to both HSBC and Barclays.

- The message exhibits poor grammar and spelling – ‘proctect’, for example. I think it unlikely that such errors would be present in genuine messages from my bank.

- The message is not addressed to the recipient (me) by name. This can indicate a message sent randomly to large numbers of email addresses.

The above points, along with the fact that I don’t actually manage my bank account online, convinced me not to follow the instructions in the message. Yet despite all these warning signs, some people do hand over their details in this way.

It’s very important not to click on any links in these sorts of messages. Even if you don’t enter your account details, making any response at all may confirm to the phisher that your email address is valid, leaving you open to further hoaxes and spam. Simply clicking on a link also risks your computer being infected with malware that could distribute the same message to all the email addresses – including those of your work colleagues, family and friends – stored on your computer.

One way to check this kind of message is to position your mouse pointer over the link (‘Click here’ in the Figure 10 example) and look at the web address that appears either as pop-up text or at the bottom of the message window. If it seems to be unrelated to the sender of the message then you should be even more suspicious. After receiving the email shown in Figure 10, I searched online and found a reputable site (millersmiles.co.uk) that contained the information shown in Figure 11.

This is a screenshot of a web page describing a phishing email very similar to the one in Figure 10. It points out that the email sends recipients to a spoof website that looks nothing like the real bank site, and that HSBC Bank never send their users emails requesting personal details in this way.

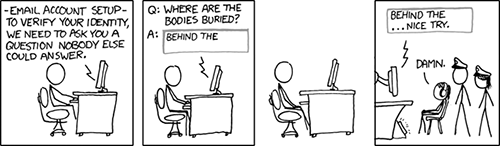

Most phishing messages try to get you to provide some personal information (Figure 12). Clearly those trying to get your online banking details are aiming to get access to your money. However, others could be trying to access your email, blog, instant messaging or online auction accounts (if you have any), then use these accounts to distribute more phishing emails.

This is a cartoon strip with four pictures. It shows an online exchange between one person (shown in the first three pictures) and three people shown in an office in the fourth picture, two of whom are wearing peaked caps.

The first picture shows the single person reading instructions from a computer screen. The instructions say ‘Email account setup. To verify your identity, we need to ask you a question nobody else could answer.’

The second picture has a question and answer, saying ‘Q: Where are the bodies buried?’ The person starts to type an answer of ‘Behind the’.

The third picture shows the person has stopped typing and is thinking.

The fourth picture shows the three people reading what the first person types. The answer they see says ‘Behind the … Nice try.’ One of the three responds with ‘Damn.’

If you have a job that provides you with an email account then you have probably also seen messages claiming to be from your company’s IT department, asking you to enter your username and password into a website to reset your email account. I’ve certainly had them sent to my Open University email account. As with requests for you to disclose your financial details, you should be careful when disclosing your username and password. A phone call to the relevant people in the company should be sufficient to find out whether or not the request is genuine.

4.5 Managing your identity online

[Break point. This would be a good point to take a break if you need to do something else before returning later.] As we live more of our lives online, so it becomes more important for us to be aware of and, as far as possible, try to manage the information that others can access about us online. As a general guideline, before you place any kind of information about yourself on the Web you should think about the impression you would like potential employers, new friends, your parents or your children to get of you if they searched for you online. Stories of people being disciplined or even losing their jobs as a result of inappropriate comments or photographs on their blogs or social networking sites show that this isn’t a hypothetical situation. For some employers, checking the information that is available online about job applicants is as much a part of the selection process as taking up references.

Activity 10 (exploratory)

Enter your name into a search engine and review what you find.

- a.What is revealed about you?

- b.What is revealed about other people with the same name as you? If you have a common name then it may be hard to tell the difference between you and others with the same name. However, you should be able to get an impression – and possibly even some photographs – of a few individuals who share your name. If you can’t find anyone with your name, try looking for the name of a family member or friend.

Comment

- a.My name (John Woodthorpe) isn’t very common, so most of the links I found do refer to me. They include articles and papers I wrote both before and after I started working for The Open University, as well as links to the OU website and some defunct ones to a website I used to run and took down many years ago. I didn’t find my Facebook page because the privacy settings mean that it isn’t publicly available.

- b.There were several references to a company director who shares my name. I also found a couple of Facebook users, including one in New Zealand. Most surprisingly, I found a reference to a couple whose names are the same as mine and my wife’s – as far as I can tell, they run (or perhaps ran) a guest house in Bulgaria. In addition, there were several links to genealogy sites where people are trying to trace their family trees, and quite a few references to people called John from places called Woodthorpe.

This so-called ‘ego surfing’ or ‘vanity surfing’ is an interesting thing to do from time to time. Overall I haven’t found anything unpleasant or embarrassing, but I’m old enough for any youthful indiscretions to have happened long before they could have been recorded online. I also have a range of usernames that don’t resemble my real name and so aren’t easily connected to me. They aren’t used for anything nefarious, but I see no reason why I should make it easy for others to find out everything about me.

Several online communities offer good advice on managing your online identity - the links are given below. It’s not something to get overly worried about, but it is worth being aware of the impression that others can get by following the trail of your online activities.

4.6 Section summary

In this section I’ve discussed ways in which you can protect your computer and yourself online, ranging from taking sensible precautions against malware to guarding against presenting information about yourself to the world that you might later regret. In the next section you’ll learn more about the development of the computer.

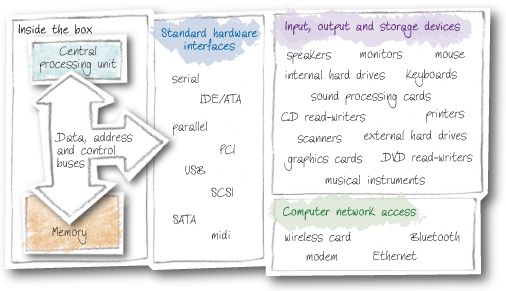

5 What’s inside my computer, and what makes it work?

The next section of this unit is based around a video called ‘Inside the box’ and should take you one to two hours to complete. It will give you an overview of a computer from the perspectives of a computer engineer and a computer scientist. The video has been divided into three ten-minute sections, which you will watch at intervals throughout the text.

5.1 Peripherals

This section will introduce you to a range of peripherals connected to a typical desktop PC, and show you how the computer engineer and computer scientist each view the communication between the peripherals and the main PC.

Activity 11 (exploratory)

Below is the video that you need to watch for this activity. This consists of the introduction and first section (entitled ‘Outside to inside – peripherals’) of the ‘Inside the box’ video. You will need your computer’s speakers or headphones to listen to it.

Transcript: Inside the box: introduction and section 1

[Graphic title: Inside the box]

[Music – duration 00:12]

[Graphic title: Outside to inside – peripherals]

[Music – duration 00:08]

This video is eleven minutes and five seconds long.

The main presenter, Spencer Kelly, and two co-presenters, Dr Darien Graham-Smith and Dr Parisa Eslambolchilar, are standing around a table discussing various computer components in front of them such as the PC, a mouse and a keyboard.

Parisa draws a diagram on a piece of paper. It depicts a large square (the computer) with a smaller box inside at the top (the processor) and another box at the bottom (the memory). In between these two boxes to the right is another box (input/output devices). Arrows (labelled data control and address buses) go to the processor, memory and input/output devices.

‘Outside to inside – peripherals’ is displayed on the screen.

Spencer disconnects the computer from all the peripherals and hands the mouse and connector, keyboard and connector, monitor and connector each in turn to Darien, who explains how they work. Parisa does likewise. She places the connectors on the input/output box on her diagram. Data is shown coming out of the input/output box.

Darien and Parisa each discuss how the printer and connector work from their own perspectives. Again data is shown coming out of and going into the input/output box when the connector and the printer are placed near it. The presenters then continue to discuss standards.

A digital camera is then connected by Darien to the computer using a connector. The connector is then placed on the input/output box on the diagram. They then look at the mains plug and discuss its purpose.

The peripherals are placed next to the diagram and data is shown flowing between these.

End of text description.

5.2 Opening the case

Figure 13 shows a picture of the inside of a fairly standard desktop PC (click on this to see a larger view with labels).

To make sense of all this clutter I could take a computer engineering view of the system and think about the detailed wiring, voltages, electric currents, circuit boards, power supplies, cooling fans, etc. However, few people really need to think about a computer system in this way. Instead we can think of the computer as a series of standard parts connected by standard wiring, with standard communication protocols exchanging data in standard formats.