4.4 Supermarkets – low betas but high risk?

For those seeking to invest cautiously in UK equities, the draw of buying shares in the major supermarket companies looked like a safe bet. With secure footholds in markets where consumer demand was guaranteed, the supermarkets looked like equity investments that would deliver steady dividends and few share price shocks. Their low betas pointed to their relatively low risk as equity investments.

Then came 2014 – as Table 4.5 shows, the UK supermarket groups belied their image as ‘boring’ stock – although not in the way that pleased those investing in them.

In a year which saw the FTSE 100 treading water, these ‘low risk’ stocks lost around half their value.

| 25/11/13 | 24/11/14 | Move in Year | Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTSE-100 Index | 6695 | 6727 | +0.5% | |

| Morrison | 276 | 151 | -45.3% | 0.36 |

| Sainsbury | 414 | 223 | -46.1% | 0.79 |

| Tesco | 358 | 164 | -54.2% | 0.79 |

So had supermarkets suddenly become high-risk stocks? Were their betas wrong?

The probable answer is that 2014 proved to be the ‘exception that proved the rule’ for supermarket stocks. They remain stocks which normally experience less volatility than the market as whole. In 2014, though, a major shift occurred to the expected profits of Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Morrisons due, primarily, to changes to the structure of the (food) supermarket industry in the UK. The growing market share of relative new entrants like Lidl and Aldi, as well as economy stores like Poundland, impacted on the market leaders.

Additionally, changes to shopping habits, which are seeing people move away from doing their entire weekly shop in one supermarket, are also hitting the market leaders.

Investors took this to be a realignment of medium to longer term profit expectations of the leading supermarkets and so priced their shares down accordingly.

So, supermarket shares are now still low volatility stocks albeit from a lower share price position. One-off quantum shifts do not make betas rise sharply. What makes a beta rise is when a share price is consistently more volatile than the market as a whole.

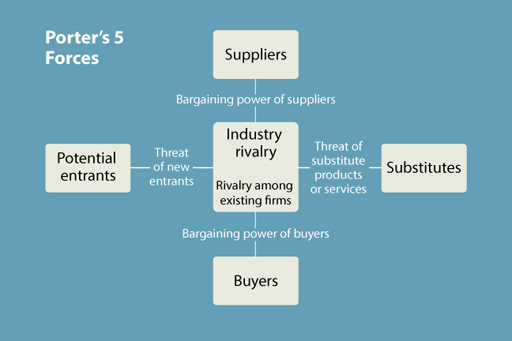

To understand more about what has happened to the UK supermarket industry in recent years let us look first at the financial environment within which these organisations conduct their business. To do this we will use ‘Porter’s five forces model’, a well-established model, first developed and published by Michael Porter in 1979 and developed further in 1996 and 2008 (Porter, 1979; 1996; 2008). This model, set out in Figure 13, identifies the five forces that will heavily influence an organisation’s financial strategy.

At the centre of the model is ’industry rivalry’. This relates to the extent of the existing competition in the markets in which the organisation conducts its business. At one extreme, markets can be very competitive – particularly when the products offered are identical (‘homogeneous’) in nature and when there are a large number of suppliers. In these circumstances, the organisation has little power to determine the market price of its products. The prices are set by the market as a whole and the organisation has to be a ‘price taker’, that is, accept the fact that it has to charge its customers the price currently prevailing in the market. Its ability to operate in this market, and to make sufficient profits to sustain it in business, will be dependent on its ability to contain business costs to a level below the income it receives from selling its products. Organisations operating in competitive markets cannot, therefore, be inefficient in managing their operations as there is no scope to pass on the cost of such inefficiencies to customers.

At the other extreme, the organisation may be a monopolist – the only supplier or one of only a very few suppliers (in that case: oligopolist) − of a particular product. Here, the organisation has considerable power in setting the market price of the product. Note, though, that in this environment the organisation’s power over the market is not total since, if it sets prices too high, some customers, at least, will forego the product as they may no longer be able to afford it.

So what has happened to the major UK supermarkets in recent years? Simply put, market entrants over the past decade have created more competition in the industry, resulting in lower profit margins for Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons.