6.2.2 Human behaviour in the business environment

This section uses some high profile misdemeanours in the financial world to explore the impact of the business environment on human behaviour. Watch the following video, which provides more detail about the subject of behavioural finance, before we start to explore specific biases that affect financial decision-making.

Transcript

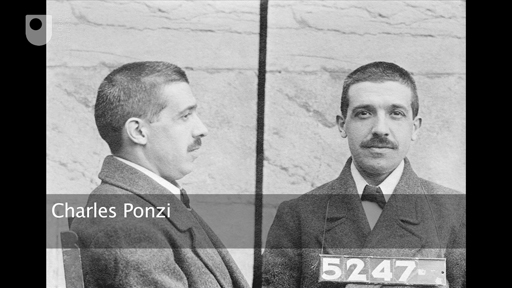

When we think of the financial risks associated with errant human behaviour, we may think of exceptional circumstances where somebody has acted outside of the law. This would include fraud for personal gain such as the ‘Ponzi scheme’ run by Bernard Madoff that cheated investors out of billions of dollars by lying about investment returns. Or fraud to cover up mistakes – rather than for personal gain – as with the case of Nick Leeson, whose actions brought down Barings Bank in 1995 (see Leeson, 1996).

A similar, and more recent example came in 2008, when the French bank Société Générale announced losses of some €4.9 billion as a result of trades undertaken by another rogue dealer Jerome Kerviel. Initially, at least, Kerviel was able to conceal these losses by making fraudulent entries into Société Générale’s financial systems.

Perhaps more intriguing, though, are the instances of fraud on an organisational level that require groups of people to be complicit rather than just individuals. A classic case in this respect was Enron, the US energy trading company. The company was found to have misled investors and regulators about their profitability. It eventually went bankrupt in 2001, leaving investors with losses estimated at upwards of $60 billion. The scale of the deception required the active involvement of many people within Enron. Others who may not have been directly complicit would at least have been aware of the deception.

With the cases of individual fraud, it is easy in retrospect to think of the individuals responsible as one-off ‘rogues’. But when considering fraud on an organisational level, it is far harder to imagine how this could happen. Surely the whole organisation was not staffed entirely of ‘rogues’? Certainly many, if not most, of those caught up in these situations will have found themselves involved by no design of their own.

The explanation could, therefore, be that human behaviour in the workplace is heavily influenced by the business environment. In these extreme cases of organisational fraud, it is hard to argue against the view that the environment and the actions of others are major contributory factors to how people behave. Even in the examples of individual fraud, it is highly unlikely that someone can act for the period that they have without the knowledge or assistance of other employees. So, it could be argued that people’s behaviour can deviate dramatically from what would be rationally expected depending on the environment that they find themselves in.

Behavioural finance (sometimes referred to as BF) is defined as ‘… the study of how psychology affects financial decision-making and financial markets’ (Shefrin, 2001). Behavioural finance looks at why deviations from expected human behaviour occur and, in particular, at how environments of uncertainty and risk affect people’s behaviour.

We can probably all cite examples of poor decision-making that can at times exasperate us, something that however hard we try to explain we cannot find a satisfactory explanation for the course of action we find ourselves undertaking. These apparent inexplicable decisions are not constant; perhaps this is why they cause such exasperation when they occur. In everyday life, these irrational decisions may not cause much more than irritation – but what about when they occur in a business environment or in making important investment decisions?

The risks inherent in the inconsistencies of human decision making often go undetected and pose a genuine threat to identifying and managing risk. They are not as easily or reliably measured in a quantitative manner as other risks in business.