Session 3: Pathogens and human infectious disease

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 22 January 2026, 7:57 PM

Session 3: Pathogens and human infectious disease

Introduction

Session 3 provides a brief overview of the many different infectious agents, also known as pathogens [path-oh-jens],that cause infectious diseases in humans and the ways in which these pathogens are transmitted between people, the environment and other animals. The most numerous pathogens are bacteria, as you will discover. In fact, there are more than twice as many different types of bacteria that cause human disease compared to the number of infection causing viruses.

In the video you'll learn more about these two different types of pathogens and how they are different from one another.

Transcript

CLAIRE ROSTRON: Let's start answering this question by pointing out why they are the same. Bacteria and viruses are pathogens, or infectious agents, meaning that they are two of the causes of infectious diseases. An example of a bacterial disease would be meningitis, whereas an example of a viral disease would be rabies. But these are characteristically different. A bacteria is considered to be a living organism, whereas a virus is not. Why is this? Well, they are structurally very different.

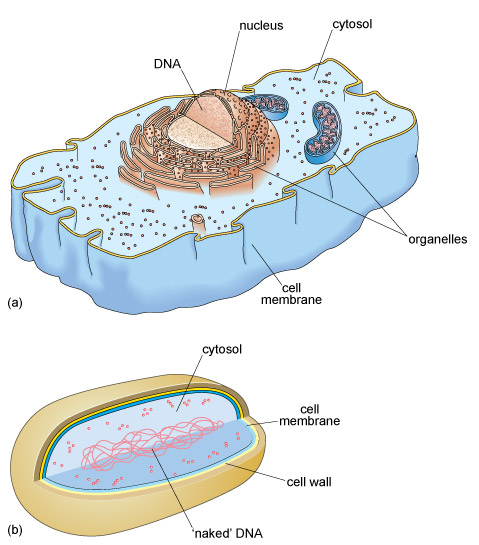

In a typical animal cell, the genetic material, in the form of DNA, is held in the nucleus. The cell is surrounded by a cell membrane that protects the cell from the environment outside. Also within the cell are structures called organelles, which can be considered to be the cellular machinery. For example, the machinery that creates fuel to help the cell perform its functions.

In the bacterial cell, the DNA is not contained within a nucleus, and there's a noticeable lack of organelles. However, the bacterial cell is still considered to be a living organism because it has a cellular-type structure, with DNA that programmes the functioning of that organism.

Viruses, however, are not considered to be living organisms because they do not consist of cells. They are made up from very short strands of genetic material, which cannot function independently and can only replicate by hijacking the genetic material in the cells of a host, causing that cell to assemble new virus particles that can pass through the cell membrane of the host cell and into the external environment.

Of course, there is another very important difference between bacteria and viruses. Bacteria can normally be killed by antibiotic drugs, whereas viruses cannot. In this Open Learn course, you'll be learning more about bacteria and viruses, as well as other types of pathogens, like parasites and fungi.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

3.1 How many pathogens cause human disease?

Human infectious diseases are caused by over 1400 different pathogens (Table 1). Some of the diseases they cause are never or rarely fatal, but nevertheless result in millions of acute illness episodes and chronic disabling conditions. Only about 20 pathogens have high mortality rates, causing around two-thirds of the estimated 10 million human deaths due to infection every year. In this section we will focus on some of the most important pathogens, which affect huge numbers of people across the world.

| Pathogen type | Number causing human disease |

|---|---|

| Parasites: multicellular | 287 |

| Protists: single-celled | 57 |

| Fungi: e.g. yeasts | 317 |

| Bacteria | 538 |

| Viruses | 206 |

| Prions | 2 |

| Total | 1407 |

Examine the data in Table 1. We have listed the pathogens in size order: from the largest – the multicellular (which means many celled) parasites – in the top row, to the smallest – prions [pry-onz] – in the row second from bottom, above the column total. The distinctive biology of each of the six pathogen types is described in later sections, along with the most important diseases they cause.

The table also shows how many pathogens other than the more familiar bacteria and viruses infect us. You may have been surprised that 287 different multicellular parasites and over 300 types of fungi [fung-guy] are human pathogens.

Bacteria are the most numerous human pathogens and their impact on human health is likely to increase as many become resistant to antibiotics – the drugs specifically used to control them.

Humans are also infected by over 200 viruses, but only two prions are currently known to cause human disease. Unlike the other four pathogen types, viruses and prions are not composed of living cells. It will help you to understand their biology if we take a short detour to describe the structure of cells. When you get to viruses and prions you will see how different they are from cell-based life forms.

3.2 Cells and their relationship to pathogens

Parasites, protists, fungi and bacteria are composed of cells – the basic unit from which the bodies of living organisms are constructed. Parasites and other animals (including humans) and plants are multicellular, i.e. their bodies consist of many cells. Pathogenic protists and bacteria are single-celled organisms. Fungi can exist in single-celled and multicellular forms, and some fungal cells can merge to form long filaments.

Bacterial cells are different in several respects from the cells of all other organisms. Figure 1a is a highly simplified diagram of an animal cell and Figure 1b represents a typical bacterium.

Part (a) is a simplified 3D diagram of an animal cell. The cell is bounded by a thin, flexible cell membrane. Inside is the nucleus, which is also membrane-bound and contains the DNA. Also present are membrane-bound components called organelles, and many tiny structures called ribosomes. The fluid interior of the cell is called the cytosol. The ribosomes are either free in the cytosol or attached to the outside of membranous sacs. Part (b) is a simplified 3D diagram of a bacterium. A thick cell wall surrounds the cell membrane. There is no nucleus nor are there any interior membranes; the ‘naked’ DNA and all the ribosomes are free in the cytosol.

There are many similarities between animal and bacterial cells: for example, they both have a cell membrane, a complex structure that controls the passage of substances into and out of the cell. Around 70% of the internal contents of both cell types is a watery fluid called cytosol [sigh-toh-soll], in which many chemical reactions take place.

The cytosol of animal, plant, protist and fungal cells contains many different structures, collectively called organelles [or-gan-ellz]. The largest single organelle is the nucleus [nyook-lee-uss] enclosing the genetic material (DNA) that governs the functioning of the cell.

How does the description of an animal cell that you have just read differ from what you can see of the bacterium from the diagram in Figure 1b?

The bacterial cell doesn’t contain any organelles and its DNA is ‘naked’ in the cytosol, not enclosed in a nucleus. Note that bacteria also have an additional protective layer (the cell wall) outside the cell membrane, surrounded by a slimy coating.

Next, we briefly explain how all living organisms, including bacteria, are distinguished from each other by unique scientific names.

3.3 Organisms and their scientific names

Organisms are classified by scientists into hierarchies that reveal how they have evolved from common ancestors. We are not concerned with this evolutionary hierarchy in this course, but you should understand how the unique two-part Latin names that distinguish different organisms unambiguously to scientists have been derived.

The first part of the Latin name indicates the genus [jee-nus] of the organism (the genus is a subdivision of the much larger family to which the organism belongs). Organisms in the same genus are very closely related. The second part of the Latin name indicates the species [spee-sheez] of the organism, which tells you that it has certain unique characteristics that distinguish it from all other species in the same genus. The individual members of a species are not identical; for example, there are obvious differences between individual humans, but we all belong to the species Homo sapiens [homm-oh sapp-ee-yenz].

Scientific publications give an organism’s two-part Latin name in full the first time it is used, but generally abbreviate the genus to its first letter thereafter, as in H. sapiens. Note that the genus always begins with a capital letter, the species begins with a lower case letter, and both parts of the name are printed in italics (or you can underline them in handwritten notes).

Viruses and prions are not organisms, so they don’t have Latin scientific names. With these points in mind, we can describe the biology of each of the pathogen types that were listed in Table 1.

3.4 Introducing parasites and protists

The term parasite refers to an organism that lives in or on the body of another organism (its host) and benefits at the host’s expense, so strictly speaking all pathogens are ‘parasites’. However, in discussions of human infectious diseases, the term is restricted to:

- multicellular parasitic worms

- pathogenic protists: single-celled organisms with similar cells to those of animals (multicellular protists exist, but none are human pathogens).

In 2013, the World Health Assembly identified 17 so-called ‘Neglected Tropical Diseases’ affecting over one billion people; it is notable that eight are caused by parasites and three by protists. Figure 2 shows sites on the surface or inside the human body that parasites and protists can infect. Click or tap on each of the labels in Figure 2 to reveal a brief description in a box below the diagram of the disease states the pathogen causes and the site(s) it occupies in the body.

This is a diagram of the human body annotated with names of a number of parasites and pathogenic protists to show the organs and tissues that they infect. These are: head louse – scalp; tapeworm cysts – brain; Toxocara – brain, eye, lung and liver; filiarial worm – eye and lymph nodes (e.g. those under the arm); Plasmodium – brain, bloodstream and liver; Trypanosoma – heart and bloodstream; liver fluke – liver and gall bladder; Entamoeba histolytica – liver and intestines; Schistosoma – liver, intestines and bladder; tapeworm – intestines; hookworm – intestines; Trichomonas – bladder; and body louse, scabies and ticks – skin surface. Clicking on the labels reveals some details about each parasite or pathogen. These read:

- head louse causes irritation; site: head hair

- tapeworm cysts cause epileptic seizures; site: brain

- Toxocara [tox-oh-kah-rah] adult can cause blindness and liver damage; sites: eyes, brain, muscle and liver

- Plasmodium [plaz-moh-dee-um] causes malaria; sites: red blood cells, liver and brain

- filarial [fill-air-ee-al] worm can cause fever, elephantiasis and river blindness; sites: lymphatic system and eyes

- Trypanosoma [trip-pan-oh-soh-mah] cause sleeping sickness; site: blood

- liver fluke cause chronic liver disease; sites: liver and gall bladder

- Schistosoma [shist-oh-soh-mah] cause bilharzia; sites: intestine, liver and bladder

- Entamoeba histolytica [en-tah-mee-bah hist-oh-lit-ik-ah] cause amoebic dysentery; sites: liver and large intestine

- hookworm can cause anaemia and protein deficiency; site: large intestine

- tapeworm can cause anaemia and malnutrition; site: intestines

- Trichomonas [trik-oh-moh-nas] cause irritation and discharge; site: reproductive tract

- body louse can transmit typhus and trench fever; site: in clothing and on skin

- ticks cause irritation, can transmit typhus and various fevers; site: on skin, feed by sucking blood

- scabies cause severe irritation; site: on top of skin, males dig burrows under skin

3.5 Ectoparasites and endoparasites

The 287 species of multicellular parasites in Table 1 all live inside the human body. They are the major category of multicellular parasite and are known as endoparasites (endon is Greek for ‘within’). Endoparasites can invade vital organs or live in the gut, bloodstream or tissues. The endoparasites of humans belong to four types of worms:

- roundworms

- tapeworms

- filarial (thread) worms

- flukes (or flatworms).

The examples that follow illustrate the often forgotten impact of multicellular endoparasites on human health and the variation in their life cycles and transmission routes. However, before we go on, it is worth observing that there exists an additional category of multicellular parasites: ectoparasites.

Ectoparasites are invertebrates (animals without backbones) that live on the surface (ektos is Greek for ‘outside’) of the human body, such as head lice, body lice and ticks. Their bites can cause intense irritation and they also transmit some potentially life-threatening pathogens to humans, such as the bacteria that cause typhus [tye-fuss]. People with typhus develop a very high fever (body temperature well above the normal 37 °C), severe headaches, muscle pain and a dark rash. It can spread rapidly in overcrowded communities, where lice and ticks proliferate because people cannot easily wash themselves or their clothes (Figure 4).

3.5.1 Roundworms, hookworms and anaemia

Pathogenic soil-transmitted roundworms (or nematodes) are transmitted harmlessly from person to person via worm eggs shed into the soil in human faeces. At least 1700 million (or 1.7 billion) people worldwide have these worms in their intestines. Children in heavily infected communities may harbour more than 1000 worms, causing diarrhoea, discomfort and restricting the child’s growth.

Can you suggest how children get worm eggs onto their hands and transfer them from hand to mouth?

Particles of dirt contaminated with worm eggs stick to the hands when children play or work on soil; if hands aren’t washed before eating, the eggs can easily transfer to the child’s mouth.

Lack of water and soap for handwashing, as well as lack of sanitation, are major contributory factors in hand-to-mouth transmission of all pathogens, not only worms.

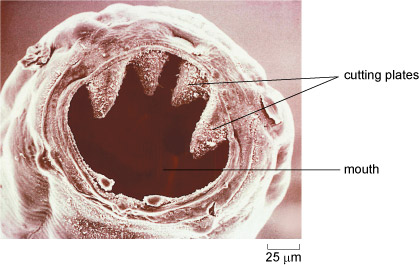

Hookworms (Figure 5) are soil-transmitted roundworms measuring 5–10 mm (millimetres), which hook onto the inner wall of the human gut and suck blood from the surrounding blood vessels. Over 400 million people are infected with hookworms and as a result suffer a type of anaemia [an-ee-mee-ah] due to loss of red blood cells. Anaemia caused by hookworms contributes to stunting in children (being short for their age) and wasting (being underweight for their height). Hookworms also present a risk to pregnant women and their unborn or newborn babies due to the adverse effects of maternal anaemia.

This scanning electron micrograph shows the large round open mouth of the hookworm and its four wedge-shaped teeth or cutting plates – a large one either side of two smaller ones. At the bottom right of the figure is a small scale bar indicating a length on 25 micrometres (μm) on the figure. This can be used to measure the following approximate dimensions: width of head, 225 μm; width of mouth, 125 μm; length of small and larger cutting plates, 30 and 40 μm respectively.

The scale bar in the bottom right corner of Figure 5 gives a measurement in micrometres (µm); one micrometre is one-thousandth of a millimetre (mm) and one-millionth of a metre (m).

3.5.2 Tapeworms and epilepsy

Tapeworms are easily distinguished from roundworms because they have long flattened bodies (resembling a tape, hence their name). They are the largest of the worms that infect people; some species can grow up to 10 metres in length. Different species of tapeworms are parasites of cattle, pigs, dogs and even fish, but they can also infect humans.

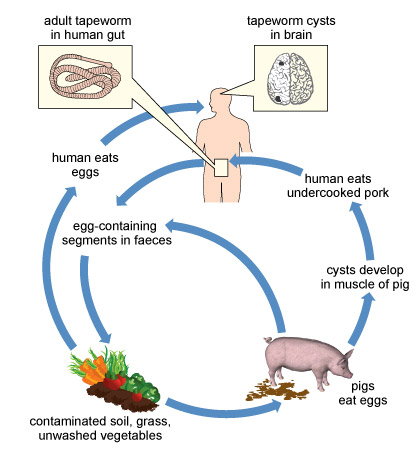

Although deaths due to tapeworms are rare, they cause pain in the abdomen and reduce the nutrients available to their human host. However, the main health risk is from epilepsy, i.e. brain seizures or fits. Figure 6 shows the life cycle of the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium), the species associated with acquired epilepsy. Contrary to popular belief, people are rarely infected through eating undercooked pork.

This is as a pictorial life cycle diagram with brief descriptions of each stage in the cycle. Egg-containing segments from the adult tapeworm that is present in the gut of a pig or human host contaminate soil, grass and unwashed vegetables. Humans can therefore ingest the tapeworm eggs, and these hatch into larvae in the gut. The larvae may develop into adult tapeworms, which then reside in the gut. Some larvae may get into the bloodstream and go on to form cysts in the person’s muscles, eyes or brain. Similarly, the pig can consume the tapeworm eggs and these may develop into cysts in the pig’s muscle. So, if a human eats undercooked pork, in which the encysted tapeworm may remain alive, the cyst may go on to develop into an adult tapeworm in their gut.

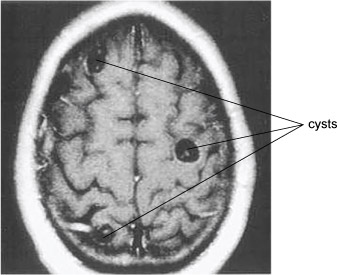

Tapeworm eggs in pig faeces contaminate land around human settlements where pigs graze. Soil is also contaminated with worm eggs from human faeces if people are forced to defaecate in the open because there is no sanitation. People are infected when they swallow the eggs in soil on unwashed vegetables or when eating with unwashed hands. The eggs hatch into larvae [lar-vee] in the human gut; larvae (singular, larva) are an immature stage of development in many invertebrates. Worm larvae may develop into adult tapeworms in the human gut, but some burrow into the person’s muscles, eyes and brain, where they ‘encyst’, i.e. become encased in a tough outer covering. Cysts in the brain (Figure 7) can trigger epileptic seizures. Around 30% of people with epilepsy in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia have pork tapeworm cysts in their brain (Ndimubanzi et al., 2010).

This figure is an X-ray photo of the brain and surrounding skull, with the front of the brain at the top of the image. Three cysts are visible as dark, roughly circular structures within the much paler brain tissue.

3.5.3 Filarial worms, elephantiasis and river blindness

Adult filarial worms are thread-like parasites measuring 40–100 millimetres in length, whose description ‘filarial’ [fill-air-ee-uhl] comes from the Latin for filament. The diseases they cause are all vector-borne, transmitted when a biting invertebrate transfers microscopic worm larvae (around 300 micrometres long) to a human host as it takes a blood meal.

The disease once known as elephantiasis because of the appearance of infected limbs (Figure 8) is properly called lymphatic filariasis [lim-fatt-ik fill-arr-eye-ass-iss]. Most cases are due to one species, Wuchereria bancrofti, transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. The filarial worm larvae block the fine lymphatic tubules that collect tissue fluid from all over the body and return it to the blood stream. The blockages cause painful inflammation and swelling, as fluid collects in the lower limbs and genitals. More than 120 million people are infected with filarial worms in 73 countries, including Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Nigeria and the Philippines, and 40 million people are severely disabled by them.

This is a photo of a man with a hugely swollen and distorted scrotum and right leg and also some swelling in his left leg. Much of the skin covering the swollen tissue is nearly black and appears blistered and scaly.

The microscopic larvae of another species of filarial worm (Onchocerca volvulus) are transmitted by blackflies that bite humans. The larvae cause skin lesions that itch relentlessly, but the larvae also invade the eyes and cause ‘river blindness’, so-called because blackflies breed in fast-flowing rivers, so this disabling condition only occurs in riverside communities.

3.5.4 Flukes, freshwater snails and schistosomiasis

Rivers, lakes and streams are also essential to the transmission of some species of flukes [flookz] or flatworms, which have flattened ‘leaf-shaped’ bodies. Around 250 million people every year are infected with blood or liver flukes from the genus Schistosoma [shist-oh-soh-mah], so the diseases they cause are called schistosomiasis [shist-oh-soh-myah-siss].

Schistosoma flukes must complete part of their life cycle in freshwater snails, which shed microscopic larvae into the water. When people enter infected water to fish or wash themselves or their clothes (Figure 9), the larvae penetrate the person’s skin along the track of hairs, usually on the legs. The larvae mature into adult flukes (10–16 millimetres long) in the person’s body. Male and female flukes mate and produce eggs with sharp spines that damage blood vessels, mainly in the liver, gut and bladder. Fluke eggs excreted in the faeces and urine of infected people are flushed into water sources in the environment, where they hatch into larvae, which reinfect aquatic snails and the cycle begins all over again.

3.6 Malaria and other protist diseases

The pathogenic protists that infect humans are all single-celled organisms, formerly called ‘protozoa’. They are responsible for a range of diseases, including:

- dysentery (bloody diarrhoea) caused by waterborne protists similar to the amoebae [amm-ee-bee] commonly found in freshwater ponds

- sleeping sickness, caused by protists transmitted via the bite of tsetse flies

- leishmaniasis [leesh-man-eye-ah-sis] transmitted by biting sandflies; Leishmania protists cause painful lesions in the skin, affecting around one million people (Figure 10a), or potentially fatal enlargement of the liver and spleen with up to 400 000 cases annually (Figure 10b).

The following activity describes the life cycle, impact and prevention strategies against the most widespread infectious disease caused by a protist – malaria.

Activity 3 Malaria: a vector-borne protist infection

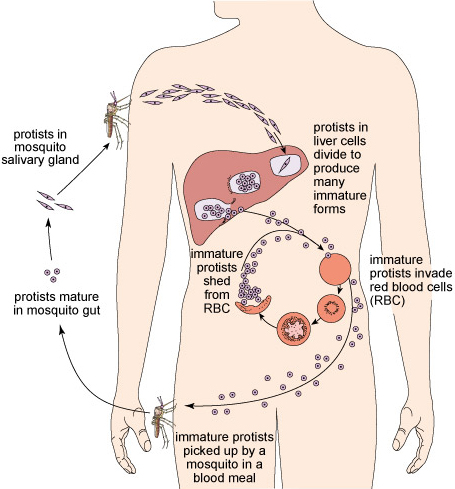

The protists that cause malaria belong to the genus Plasmodium [plazz-moh-dee-umm]. Study their life cycle in Figure 35 and then answer the questions below the diagram.

This is as a pictorial life cycle diagram of the malarial protist with brief descriptions of each stage in the cycle. When an infected mosquito bites a person to take a blood meal, mature protists, present in the mosquito’s saliva, get into that person’s bloodstream. They travel in the bloodstream to the liver, enter the liver cells and divide to produce many immature forms. These immature protists invade red blood cells and reproduce themselves. Protists are shed from the RBC and go on to invade further RBCs so their numbers increase rapidly. A mosquito that takes a blood meal from the infected person therefore picks up immature protists. These mature in the mosquito’s gut, and when the mosquito takes its next blood meal from another person it passes on the mature protists to that person, completing the cycle.

Question 1

How are the protists that cause malaria transmitted to a new human host?

Answer

When an infected mosquito bites someone to take a blood meal, protists in the mosquito’s saliva get into the person’s bloodstream.

Question 2

How do the protists get into the mosquito’s saliva?

Answer

When the mosquito sucks blood from an infected person or animal, the protists are drawn into the mosquito’s gut from there they migrate to its salivary glands.

Question 3

Which human cells are routinely invaded by malaria protists?

Answer

Liver cells and red blood cells. (The protists are less than 5 micrometres (µm) in diameter at this stage – small enough to get into a red blood cell.)

3.7 Fungal pathogens

You are probably most familiar with large edible fungi (mushrooms) and the single-celled yeasts used in making bread and beer, but over 300 fungal pathogens cause infectious diseases in humans. They are rarely fatal, except in people whose immune system cannot protect them from infection. Fungal cells in the soil can infect humans through breaks in the skin, but they can also form ‘spores’ encased in a rigid capsule, which can easily become airborne and cause respiratory diseases if inhaled.

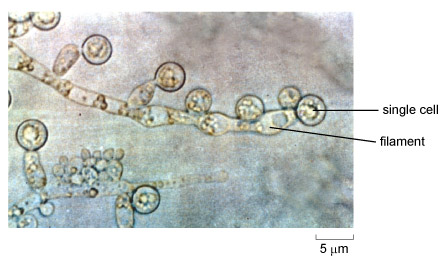

Among the most common fungal infections in humans are ringworm, athlete’s foot and thrush. Candida albicans, which causes thrush, exists in two forms – as single-celled yeasts (measuring 3–5 micrometres) and as multicellular filaments which can be several millimetres in length (Figure 12). Thrush is characterised by inflammation, especially in the mouth, and also in the vagina where the infection causes intense itching.

This is a micrograph showing Candida albicans filaments and roughly spherical single cells, which bud off from the filaments. The single cells have a thicker wall then that of the filaments. A 5 micrometre scale bar is included. The individual cells measure between 4 and 5 μm in diameter and the filaments are 2 to 3 μm thick.

3.8 Bacterial pathogens

Bacteria are the Earth’s most ancient organisms, evolving over 3000 million years ago. They are also the most numerous: the mass of all the bacteria in the world may exceed the combined mass of all the plants and animals. Each bacterium is a single cell that can multiply very rapidly – in as little as 20 minutes in some species.

Most of the bacteria that live in or on the human body are beneficial. The number of ‘friendly’ bacteria living in your gut is around 10 times the number of human cells in your whole body! These beneficial organisms are called commensal bacteria. Commensal [coh-mens-uhl] means ‘sharing the same table’ – a name that reflects the fact that some bacteria in the gut enable us to digest plant-based foods.

Commensal bacteria also have a role in protecting us from some infectious diseases. They occupy habitats in the body that could otherwise be colonised by pathogens such as Candida albicans, the fungus that causes thrush. Fungal cells that occur naturally in the mouth and vagina are kept in check as long as commensal bacteria occupy the available space and prevent the fungi from acquiring enough nutrients for growth. However, thrush often develops after treatment with antibiotics to control a bacterial infection.

Can you suggest why thrush is more common after taking antibiotics?

The antibiotics kill commensal bacteria as well as harmful ones; in the absence of commensal bacteria, fungal pathogens can obtain enough resources to multiply and cause the symptoms of thrush.

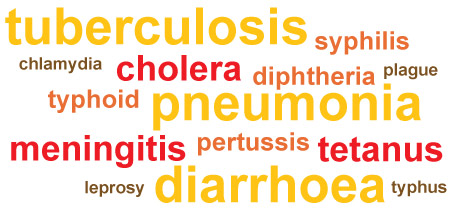

Over 500 species of pathogenic bacteria cause a diverse range of human infectious diseases. Some of the most important in terms of numbers of people affected are named in the ‘word cloud’ in Figure 13.

This figure gives the names of the infectious diseases in different font sizes and contrasting colours: in the largest font, in yellow – tuberculosis, pneumonia, diarrhoea; in the second-largest font, in red – cholera, meningitis, tetanus; in the third-largest font, in orange – syphilis, diphtheria, typhoid; and in the smallest font, in brown – chlamydia, plague, leprosy, typhus.

Here we will focus on just two categories:

- diarrhoeal diseases caused by bacteria transmitted via the faecal–oral route (i.e. transmitted from faeces to the mouth, usually on contaminated hands), and in food and water

- respiratory infections transmitted primarily by airborne bacteria.

3.8.1 Diarrhoeal diseases

Cholera, caused the by the presence of Vibrio cholerae bacteria in drinking water, is a potentially life-threatening diarrhoeal disease. The disease is widespread in many parts of the developing world, but cholera was also a major cause of death in industrialised Western countries in the 19th century as discussed in Section 2.4.

However, many other pathogenic bacteria also cause diarrhoea, particularly those transmitted in contaminated food and water. They include Salmonella in raw eggs and undercooked poultry, and pathogenic varieties of Escherichia coli [esh-err-ish-ee-ah koh-lye], mainly in red meat or raw (unpasteurised) milk, but also in unwashed fruits and vegetables contaminated with faeces. Diarrhoeal diseases are also caused by some viruses and protists.

Around 1.5 million (1 500 000) people die from diarrhoeal diseases every year, most of them young children (Figure 14). If untreated, the loss of tissue fluids and essential salts in diarrhoea rapidly results in dehydration, disruption of body chemistry, and malfunction of the nervous system and vital organs. The loss can be replaced by drinking a simple oral rehydration solution (ORS) of sugar and salt dissolved in clean water until the diarrhoea subsides. Distribution of millions of sachets of ORS powder and teaching parents how to administer it is slowly reducing the mortality from diarrhoea in childhood. In severe cases, the solution may have to be given intravenously (directly into a vein).

This figure is a colour drawing of a young boy squatting down to defecate on the open ground.

3.8.2 Lower respiratory infections

Lower respiratory infections (LRIs) result in over 3 million deaths worldwide every year – more than any other category of infectious disease. Around one million of these deaths are due to pneumonia [nyoo-moh-nee-ah] caused by several species of bacteria and some viruses. The infection triggers inflammation in the lungs, which become clogged with infected fluid, resulting in severe breathing difficulties and strain on the heart.

Tuberculosis is counted separately from all other respiratory infections because the TB bacteria (Mycobacteria tuberculosis) that infect the lungs (Figure 15) can also invade other vital organs, muscles and bones. About one-third of the world’s population (over 2 billion people, i.e. two thousand million) is infected with TB bacteria, but most are unaware of it because the body’s defence mechanisms keep the bacteria in check. However, they can multiply if the body’s defences are weakened, and TB can quickly develop in undernourished people, especially if they have another illness.

Between 8 and 9 million people around the world develop TB for the first time every year, almost 9000 of them in the UK. Worldwide, this chronic infection killed 1.3 million (1 300 000) people in 2012 – a death toll that has been slowly increasing in the 21st century. The resurgence of TB and its increasing resistance to antibiotics means that it has been classified as a ‘re-emerging infectious disease’.

3.9 Viral pathogens

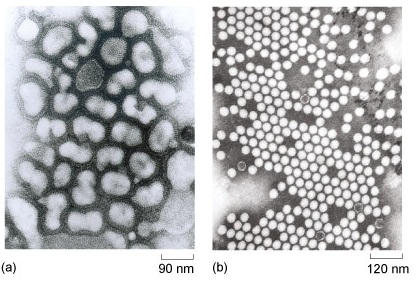

Remember that viruses are not regarded as ‘living’ organisms because they don’t consist of cells. You could think of them as minute containers for one or more short strands of genetic material and a few other chemicals. Most viruses are about 10 times smaller than typical bacterial cells, and 100 times smaller than typical animal cells. They are so small that they can only be photographed with the huge magnification made possible by an electron microscope (Figure 16).

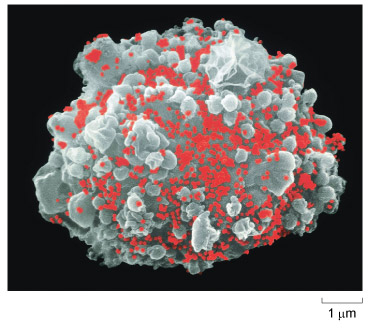

Viruses can only reproduce new virus particles or virions [vih-ree-onz] by invading a living cell. The genetic material of the virus redirects the genetic material of the host cell and causes it to assemble thousands of new virus particles from the naturally occurring chemicals within the cell. Once assembled, each virus particle remains the same size (i.e. it does not grow). Many viruses eventually kill the host cell they infect, for example when the new virus particles disrupt the cell membrane as they are shed into the surrounding environment, where they can infect new cells and begin the cycle of reproduction all over again (Figure 17).

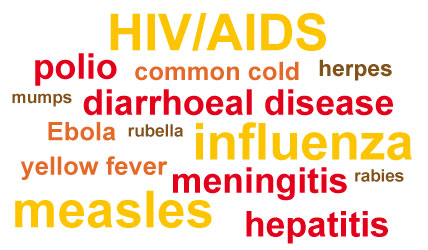

Viruses don’t have Latin species names but are named after the disease they cause: for example, measles virus, polio virus, and so on. Figure 18 is a ‘word cloud’ of some diseases caused by a few of the 206 different viruses known to be human pathogens. Around 37% of these viruses cause emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) – a much higher percentage than for any other pathogen type (Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005). Their routes of transmission are highly varied and include:

- airborne viruses causing respiratory diseases, e.g. influenza

- faecal–oral transmission of rotaviruses, which cause more cases of diarrhoea than any other pathogen

- vector-borne transmission, e.g. of yellow fever viruses by mosquitoes

- transmission via contact with infected body fluids, e.g. HIV/AIDS and Ebola virus disease.

This figure gives the names of the infectious diseases in different font sizes and contrasting colours: in the largest font, in yellow – HIV/AIDS, influenza, measles; in the second-largest font, in red – polio, diarrhoea, meningitis, hepatitis; in the third-largest font, in orange – common cold, Ebola, yellow fever; and in the smallest font, in brown – herpes, mumps, rubella, rabies.

We now conclude this tour of pathogen biology with a brief mention of the least understood category – the prions.

3.10 Prions

Prions are a very unusual form of infectious agent, consisting of a misfolded version of an otherwise harmless brain protein called prion related protein (PrP). Remarkably, prions are able to turn molecules of normal PrP into more prions, which leads to a chain reaction causing the accumulation of more and more prions. Prions then aggregate into clumps or plaques [plahks] in the brain, causing surrounding brain cells to die, so the brain develops a spongy appearance. This, in turn, causes muscle wasting and loss of muscle control. This resulting inability to coordinate breathing ultimately leads to death.

Some cases of prion disease are inherited (passed on from parents to their offspring), but prions are also considered to be infectious agents because they can be transmitted between humans, or between humans and animals. People can become infected by eating the brains or nervous tissue of animals or other people with prion disease.

The best known examples of prion diseases are BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy, popularly known as ‘mad cow disease’) in cattle, and vCJD (variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease) in humans. BSE is caused by cattle-to-cattle transmission, vCJD is caused by humans eating products derived from cattle with BSE. The transmission of prions between humans is of course very rare, but has been documented in certain Papua New Guinean tribes that practice funerary cannibalism – the eating of dead family members – where it causes a disease known as Kuru. Understandably, funerary cannibalism is now strongly discouraged.

Session 3 quiz

This quiz allows you to test and apply your knowledge of the material in Session 3.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you're done.

Summary to Session 3

Now that you have completed Session 3 you should be aware of the incredible range and diversity of pathogens that infect humans and cause disease. This gives you some idea of the challenge faced by scientists and health care professionals in treating and preventing infectious diseases.

We have introduced you to the multicellular endoparasites; four categories of worm (roundworms and hookworms, tapeworms, filarial worms, and flatworms or flukes) that cause a variety of diseases by invading vital organs or living in the gut, bloodstream or tissues. Smaller in size are protists – unicellular pathogens that cause conditions such as sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis and malaria). Next you learned about fungal pathogens and bacteria. Pathogenic bacteria cause a wide range of diseases (e.g. cholera and tuberculosis) while ‘friendly’ commensal bacteria can be protective against pathogens. You should be aware that the antibiotics used to treat pathogenic bacteria also kill commensal bacteria, which can increase the risk of fungal and other infections. Finally, you have been introduced to the two smallest types of pathogen – viruses and prions – which are not formed from cells so are not considered to be alive. Diseases caused by infectious prions are relatively rare but the same cannot be said about viruses, which cause some of the most common infectious diseases such as influenza. Viruses also cause a considerable proportion of emerging infectious diseases and exhibit a remarkable range in their modes of transmission.

Taking all this together, it should be clear to you that there is no such thing as a generalised pathogen – even within the same category of pathogen they tend to behave differently! It is therefore unsurprising that the challenge to human health posed by infectious diseases shows little sign of abating.

You can now go to Session 4.

References

Acknowledgements

This unit was written by Basiro Davey, Carol Midgley, Claire Rostron and Daniel Berwick.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this unit:

Figure 4: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images News/Getty Images/Universal Images Group

Figure 7: DeGiorgio, C. M. et al. (2004) ‘Neurocysticercosis’, Epilepsy Currents, vol. 4, no. 3, pp.107–11, American Epilepsy Society

Figure 8: Andy Crump/TDR/WHO/Science Photo Library

Figure 10a: WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 11b: World Health Organization

Figure 12: GrahamColm. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Figure 14: Rod Shaw/WEDC, Loughborough University

Figure 15: Deni McIntyre/Photo Researchers/Universal Images Group

Figure 16a: CDC/Dr Erskine Palmer

Figure 16b: CDC/Dr Fred Murphy, Sylvia Whitfield

Figure 17: NIBSC/Science Photo Library

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Copyright © 2019 The Open University