IT: device to device communication

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 5 May 2024, 6:50 PM

IT: device to device communication

Introduction

This course looks at communication systems where devices are the main players, passing information to and from each other and possibly acting on that information to produce some kind of outcome. In these interactions, people may not be involved at all, or may have roles that are limited only to the initial setting of schedule (such as when certain tasks should be performed) and parameters (such as particular conditions that should be satisfied before a task is performed). Some people may see this as liberating – relieving humans from the tedious tasks of everyday living. Some may see it as threatening – taking control away from humans and placing it with the computers and machines.

How do devices 'talk' to each other? What technologies and processes are involved? What kind of world does it create? These topics, and others, will be explored in this course.

We then look at wired and wireless communication technologies, introducing you to some of the key methods currently in use.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Computing & IT

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand and use correctly terms introduced in this course in relation to communication networks

understand general principles involved in data exchange between IT devices

work with numbers expressed in scientific notation, and use the Windows calculator to perform calculations on these numbers.

1 Communication between devices

1.1 Getting an overview

This section starts with an article from a technical journal – the sort that is read by academics and professionals working in a related technical field. It sets the scene for some of the technologies and issues that you will be encountering later in this course.

We're not going to ask you to read the entire article, but we would like you to get an idea of the article's contents, the kind of points the author is making, and the range of issues that it throws up. With this aim in mind, we're going to lead you through a method of getting an overview of the contents of a document without actually having to read it through completely.

When reading any document there are some good reasons for starting off by getting a quick overview. If you are looking for some specific information, an overview enables you to assess whether the document contains anything that is of use to you. (There's no point spending more time ploughing through it only to find it doesn't hold what you were looking for.) If it does, you might choose to concentrate only on the section that is of interest to you. On the other hand, if you are reading the document because you want to assimilate its entire contents then an overview gives you a familiarity with the document before you engage with it in depth. This will be easier if you know the direction in which you're heading (it's easier to navigate on a journey you've travelled before). An overview will help you to identify particular parts you may really need to focus on.

1.2 Skimming to get an overview

A well-structured document usually contains a number of clues about its contents. Skimming is the practice of finding and using these clues. These are:

-

visual clues such as a document's title, headings, subheadings, figures and figure captions; words in boldface and italics; and numbered and bulleted lists;

-

verbal clues such as the introduction and conclusion or summary, and the first (or sometimes the last) sentence in each paragraph.

Specialised documents often include a brief abstract that summarises the main points of the text. The abstract is usually presented before the main text, followed, in some cases, by a list of keywords or phrases. These provide some helpful pointers to the core points and ideas of a text. When authors write articles for professional journals they are usually asked to provide an abstract and some keywords even if these aren't to be included with the article itself. The reason for this is that the abstract and keywords can be listed in the search results when library catalogues are searched.

1.3 Skimming – an example

We'll shortly be asking you to skim an article which appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of a journal called IEEE Technology and Society Magazine. 'IEEE' is usually referred to as 'i-triple-e' and stands for 'Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers' – a professional association based in the USA.

Activity 1: exploratory

Click on the link below to open the document in Networked microsensors and the end of the world as we know it. Read the abstract and keywords (labelled 'index terms'). What do you expect the article to be about?

Click on the 'View document' link below to read Shepherd, D. on 'Networked Microsensors and the End of the World As We Know It'

Discussion

When I read the abstract, I expected the article to discuss some quite radical and unsettling future changes in the way we live our lives. The article's title includes some very emotive words: 'the end of the world as we know it', and the abstract talks about changing society significantly. I assumed these changes would involve the use of computers – perhaps in a way they are not currently used – because the abstract talks about bringing people 'into closer contact with computers'. In the list of keywords (called 'index terms' in this example) I could see the terms 'microsensors', 'networked sensors' and 'automation' so I suspected the article would be something about devices that sense physical states (such as temperature or pressure) or events (such as a particular change in physical state) and relay the information to computers. I thought perhaps this sensing and relaying of data might be done automatically, and/or the process might trigger some automatic response.

To me, it seemed clear from the abstract that the author would be looking at four main areas – manufacturing, military operations, personal health and personal freedom.

Activity 2: exploratory

Now go back to the document and skim the Networked microsensors and the end of the world as we know it article. Look for any of the visual clues listed earlier that could provide you with more information about the document's contents.

Discussion

The article uses only five sub-headings. These appear to be related to the four main areas identified in the abstract, plus what I assumed would be a concluding section ('Pros and cons abound'). I couldn't see a sub-heading relating directly to personal health, but I assumed that this would be discussed in the section headed 'Biological applications'. There aren't any figures to provide further clues.

I could see only a few instances of italicised words but these didn't help me much, and there are no numbered or bulleted lists. On the second page there is a box of large type which confirmed, rather than added to, the impression I'd gained from the abstract.

Activity 3: exploratory

Read all of the introduction, which consists of the first two paragraphs of the article, and the conclusion, which consists of the whole of the final section 'Pros and cons abound'. What additional insights to the article's contents has this given you?

Discussion

My impression from reading the introduction and conclusion was that the article would focus on future applications where miniature devices and increasingly powerful computers are linked into networks to monitor and control aspects of our environment. While identifying many of the advantages this can bring to society, I thought the article would also raise concerns about potential state control and loss of personal privacy that the use of such systems may bring.

Whilst reading the introduction and conclusion you may have noticed some numbers included in the text. Some were shown as superscripts (small figures or characters raised above the normal line of text) and others in square brackets.

Each superscript gives a cross-refrence to an endnote listed at the end of the article. Theses notes give additional information that could interrupt the smooth flow of the document if they had been directly incorporated into the text.

Each number in sqaure brackets gives an index to a reference list at the end of the document. This reference list gives details of all the original sources of information that the author has directly referred to or quoted from in the text. Another commom and often preferred method of indication for an original source is to substitute the bracketed index number for a short reference consisting only of the author's surname and the year of publication of the article – for example, (Allgood, 2001) instead of [1] in the Shephard article – and then to list all the information in alphabetical order of authors' surnames in the reference list.

Another very important reason for getting an overview of a document is that it helps you to avoid taking a passive approach when you read the document in full. A passive reading approach is one where the reader puts in very little effort. The outcome of this sort of reading tends (at best) to be a string of unconnected facts and ideas in the reader's mind, with very little coherence or structure. At worst, it can be a complete blank, where the reader has gone through the motion of reading but has actually drifted off to think of other things.

An active reading approach involves reading in a disciplined manner with some purpose, and thinking continually about what you are reading. As you skim a text, questions will probably occur to you – for example, 'What is the author trying to say here?'; 'What is the evidence for this?'; 'Do I agree?'; 'How do I feel about this?'; 'What more do I need to know?' Seeking answers to questions like these gives focus to your reading.

Activity 4: exploratory

Working from your understanding of the article, how do you think the topics it raises might have an impact on you? What questions do you hope the article will answer? What authority do you think the author has for giving his opinions?

Discussion

Here are my reactions to those questions.

The four main areas the author will be discussing could each have an impact on my life, but 'personal health' and 'personal freedom' sound as though they will have a more direct effect on me. I feel intrigued but slightly anxious. I think that the health effects are likely to be beneficial (possibly providing earlier detection of health problems and faster, better treatment when they arise) but I do feel concerned about privacy and control. Might I have to relinquish some of my freedoms in order to gain benefits? What might these be and what is the pay-off? I notice that the article appeared in Spring 2003 and I wonder how the world has moved on since then. I wonder if the article predicts any changes that have already started to happen!

The IEEE is a reputable professional organisation so I expect that the article would have been reviewed by other professionals in the field. This leads me to feel pretty confident about the authority of the author.

As we said earlier, we're not going to ask you to read through the whole of the article – though of course you may if you wish. (Perhaps you are keen to see if it answers any of the questions you identified in Activity 4.) Instead we would like you to return only to the first two paragraphs because these give a useful introduction to the idea of devices 'talking' to each other. The rather futuristic view presented in this section introduces you to some of the things involved when devices communicate and take actions. It identifies elements that interact with each other to perform some function.

Activity 5: exploratory

What are all the elements mentioned in the first two paragraphs that enable devices to function together as an IT system? Is there anything else you can think of that would be needed?

Discussion

The extract identifies sensors, actuators, computers (processors), storage devices, and databases. But it says nothing directly about what connects all these together – the communication link – and what rules are needed to enable the devices to talk to each other.

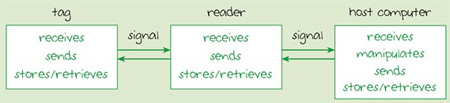

1.4 Communicating devices

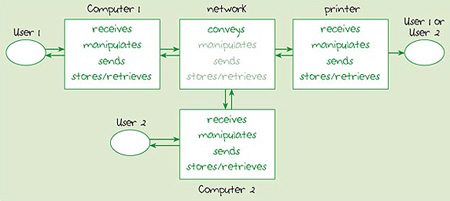

We would like you now to think about a simple IT process you are already familiar with – the process that starts when you click the Print icon on your computer's word-processor screen. For now, imagine that there is simply a point-to-point connection between your computer and the printer (as indeed there may well be) and that the printer is not being shared with other computers. So here there are two devices – your computer and your printer – each communicating with the other. The printer itself is controlled by a processor and it has memory, so you can think of it as an additional computing element. In order to 'talk' to each other, your computer and printer need some kind of communication link between them. They need protocols (rules) to establish a common language and to control the exchange of data (what to say and when to 'speak'). At a more sophisticated level they might also need some way of storing data (for example, what is known as a 'print queue') and some way of recognising and coping with errors.

Figure 1 shows a block diagram representing the computer/printer system. The communication link is point-to-point so there is no requirement for network routing, or for storing or manipulating the data as it travels through the communication link. The computer receives the print command from the user and sends data over the communication link to the printer. The paper copy produced by the printer is an output to the user.

Figure 1

It's likely that the data will need to be held in a buffer – a dedicated portion of the printer's memory – before being processed. Notice how all but one of the arrows between the elements in Figure 1 are shown in two directions. This indicates a communication path from the printer to the computer as well as from the computer to the printer. For example, at some point the buffer may become full and the printer will need to signal to the computer to stop sending data for a while. The final output from the printer is in one direction only.

Figure 2 expands the arrangement of Figure 1 to show a representation of a network where two computers share the services of a printer. Notice how there may now be a need for routing, storing and manipulating data as it travels through the communication links. (This is indicated by the lighter-shaded text in the network box.)

Figure 2

Activity 6: exploratory

Think about the additional complications of receiving and sending the necessary data between the three devices shown in Figure 2. What is needed to avoid confusion?

Discussion

In order for two computers to share one printer, it is important to be able to identify each device so that data can be correctly directed to the intended destination. Protocols are needed to establish how the printer will be shared so that one user doesn't 'hog' the resource, and to establish some way of sharing the communication link (the network) so that data from different devices doesn't become jumbled.

Now imagine that, instead of just two computers trying to share the printer, there are ten, and they are in a busy sales office. The office might use a dedicated computer (a print server) to handle the data flows between the printer and the users' computers. What happens when the printer or print server breaks down, when the network breaks down or becomes so congested that it can no longer cope with the volume of data being transmitted? Perhaps we need two or more printers, a standby server and an alternative way of routing data to the printers? So there are issues to think about like reliability, cost, capacity and speed.

Maybe you hadn't really thought of the example of computers sending data to printers as a system where devices speak to each other without human intervention. After all, it was a human who initiated the exchange by clicking on the Print icon. It also probably seems quite a long way away from the sort of systems being discussed in the extract you read at the beginning of this section. But examining and identifying the building blocks of some simple systems in this way can provide us with tools and a framework to examine more complex systems of the kind hinted at in the article.

In the next few sections you'll be looking at some of these building blocks. We shall also identify some of the human issues that can arise. For example, how does a system of devices sending data to each other affect the way we live? Is it empowering or disempowering? Does it favour some people above others? Does it threaten or enhance our rights and privacy?

Activity 7: self-assessment

Write down two reasons why networked devices need protocols when communicating with each other.

Answer

Networked devices need protocols when communicating with each other to:

-

establish a common language;

-

control use of the communication link.

2 Signals

2.1 Introduction

This section discusses methods of representing data as it travels from device to device, and some of the processes acting on it during its journey. You will be introduced to a way of expressing large numbers using a method known as scientific notation.

2.2 What are signals?

To convey data from one point to another we need to represent the data by means of a signal. We can think of a signal as a deliberate variation in some property of the medium used to convey the data. Some examples are:

-

an electrical voltage travelling along copper wires between your telephone and the local exchange;

-

pulses of light (though we might not be able to see them) in a fibre-optic cable;

-

the radio emissions that are picked up by a mobile telephone or radio receiver.

All these can provide the necessary variations to represent the data. In the first example we can relate the changes in voltage to changes in electrical energy. With the other examples – light and radio waves – we need to think in terms of waves of energy, usually referred to as electromagnetic radiation. Electromagnetic radiation is caused by changes in electrical and magnetic fields. Electromagnetic radiation can support signals even when there is no physical medium (such as a cable) involved.

2.3 Electromagnetic radiation

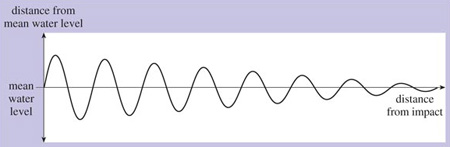

To help explain the nature of the waves of energy known as electromagnetic radiation, visualise a pond into which a stone has been thrown. If the state of the pond is 'frozen' at an instant in time, the height or depth of the water's surface at that moment will vary with distance from the source of the disturbance. If you were to cut a slice through the pond, you would see a wave shape similar to Figure 3

This image shows a ripple diagram, showing waves on a graph. A line follows the width of the diagram, which represents the 'mean water level'. On the left, one arrow points upwards and one points downwards to show the 'distance from the mean water level', above and below the mean water level. A wave runs along the line, first peaking above the mean water level, then below. The peaks decrease as the wave runs along the line. At the end of the mean water level line there is a label indicating that this is the 'distance from impact'.

The left-hand side is the point where the stone entered the water and the right-hand side is the point where the ripples have died away.

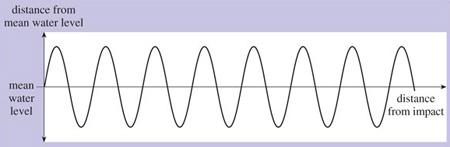

In this example, the magnitude of the peaks and troughs of the wave decreases as we move away from the disturbance and the energy is dissipated. We can say that the wave decays. If the energy wasn't dissipated and there was no decay, the shape would be as shown in Figure 4. Waveforms with a periodically repeating curve of this general shape are known as sinewaves.

This image is almost the same as the previous image, Figure 3. The only difference is that, in this case, the wave does not decrease in size along the 'mean water level' line. Each peak, above and below the line, is the same.

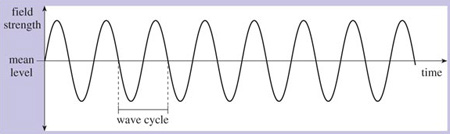

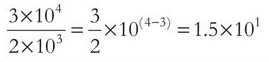

Electromagnetic waves are also sinusoidal (that is, having the shape of a sine wave). If we could freeze an electromagnetic wave at an instant in time, measure its electric or magnetic field strength at different points in space, and plot these measurements on a graph, the shape of the graph would be similar to Figure 4. But it's more usual to measure the strength of its electric or magnetic field at different instants in time as it travels through a single point in space. If we were to do this, measuring the field strength at regular intervals – say every millisecond (one-thousandth of a second) – and plot the results on a graph, it would resemble Figure 5. The wave oscillates regularly and repeatedly with time around its mean value. A single full oscillation is known as a wave cycle.

This diagram is almost the same as the previous one, Figure 4. The difference is that it shows the 'wave cycle'. A dotted line leads down from 'mean level', at the point where the wave drops to fall below the line. There is another line leading down from the 'mean level' at the next point where this occurs. The lines are joined to show that this is the 'wave cycle'.

The frequency of the wave is the number of wave cycles it completes in a single second. The unit for measuring frequency is the Hertz (Hz). For example, a wave that completes one wave cycle every second has a frequency of 1 Hz; a wave that completes 1000 wave cycles every second has a frequency of 1000 Hz or 1 kHz. Higher frequencies can be expressed in terms of MHz (megahertz – 1 000 000 cycles per second) or GHz (gigahertz – 1 000 000 000 cycles per second).

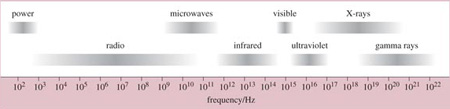

Electromagnetic waves are characterised by their wave frequency. We've already mentioned light waves and radio waves, which are examples of electromagnetic radiation. Other examples are ultraviolet and infrared rays, gamma rays, X-rays and microwaves. These are all names given to groups of electromagnetic waves that behave in a similar manner to each other. Each group occupies a particular space, determined by its range of frequencies, in the electromagnetic spectrum. The term electromagnetic spectrum refers to the entire range of frequencies of electromagnetic waves. This is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6

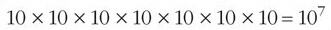

In this figure, the frequency scale is shown in Hertz along the bottom. Notice how the frequencies are expressed – for example, 102, 103, 104, etc. This is a kind of shorthand method – known as scientific notation – of expressing large numbers, which we will discuss in the next section. Notice also how the lines representing a particular group of waves are smudged at either end: this is because there are no clear start and end points to the named groups. For example, X-rays are shown to occupy a portion of the electromagnetic spectrum between about 1017 Hz and 1020 Hz, but at the lower end they blur into ultraviolet waves and at the upper end into gamma rays.

2.4 Scientific notation

To express a number in scientific notation the first stage is to divide it successively by 10 until it is reduced to a number that is less than 10. For example, to express the number 4865 in scientific notation I would divide it successively by 10 until I arrived at 4.865. Usually this will result in a number that includes a decimal fraction (the number that follows the decimal point) as well as a whole number part. In my example, 4 is the whole number part and .865 the decimal fraction.

The next stage is to give some indication of how many times the number would have to be multiplied by 10 in order to return it to its original value. In my example I made three successive divisions by 10, so I would have to multiply by 10 three times – that is 10×10×10 – to return to the original value. So my number could be expressed as 4.865×10×10×10, but this is hardly a shorthand alternative. So instead of writing 10×10×10, I can express this as 103. The first figure (10 in this case) is known as the base and the second figure (3 in this case) is known as the power or exponent (or sometimes the index). The example would be read as 'ten to the power of three'.

The final stage in scientific notation is to join together the results from the two earlier stages using a multiplication sign giving, in my example, 4.865×103.

Any number can be expressed in scientific notation. For example:

This is an equation, which reads five thousand equals five times ten, times ten, times ten equals five times ten to the power of 3.

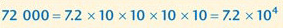

This is an equation, which reads seventy-two thousand equals seven point two times ten, times ten, times ten, times ten equals seven point 2 times ten to the power of four.

This is an equation, which reads eighty-two thousand, six hundred equals eight point two six times 10, times ten, times ten, times ten equals eight point two six times ten to the power of four.

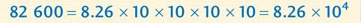

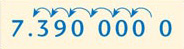

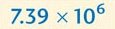

Fortunately, there is a quicker way of doing the conversions than by writing out all of the multiplication stages. I'll use the number 7 390 000 to demonstrate the method. Start by imagining there is a decimal point at the right hand end of the number. (I'll add a final 0 so that the decimal point can be seen clearly. This extra 0 is redundant since it doesn't alter the original value at all.)

Now move the decimal point one place at a time until it sits after the left-most number, and count the number of places the decimal point has been moved:

This image shows the figure seven point three nine zero, then three more zeros, then one more zero. Curved lines with arrows above the figures, from right to left, show how the decimal point has moved 6 places to the left.

(decimal point moved 6 places to the left)

Now remove all the Os at the right-hand end after the decimal point (because these are redundant) and multiply what is left by 10 raised to the power of the number of places the decimal point has been moved.

This image shows the equation seven point three nine times 10 to the power of six.

You will often see a number expressed just as the base and the power – for example 106 and 102. This is interpreted as 1×106(=1 000 000) and 1×102 (=100).

Activity 8: self-assessment

Write the following numbers in scientific notation:

-

34 200

-

5 340 000 000

-

690

-

69

Answer

Answers

-

34 200 = 3.42 × 104

-

5 340 000 000 = 5.34 × 109

-

690 = 6.9 × 102

-

69 = 6.9 × 101

In the answer to Activity 8, notice how the answer to (4) is expressed in base and power notation as 6.9×101 – meaning 'multiply 6.9 by 10 once'. Of course this gives exactly the same result as 6.9×10 and it is just as acceptable to omit the index in cases like these. In fact, it is normal to do so. However we have left it in because we want you to be aware that 101 is simply an alternative way of writing 10. Probably you are now wondering why anyone would want to bother with this, since the 'shorthand' ends up longer than the 'longhand' version. For now, just take our word for it that this method of expressing numbers will allow you to perform some arithmetical 'tricks' that can help to simplify some calculations.

2.5 Working with scientific notation using the Windows calculator

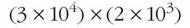

Most electronic calculators will enable you to perform calculations on numbers expressed in scientific notation. This section will take you through an exercise using the Windows calculator to perform the following calculation:

This image shows the following equation: open bracket, three times ten to the power of four, close bracket, times, open bracket two times ten to the power of three, close bracket.

Notice how we have placed the two terms in brackets. Often this is done to ensure that each step of a calculation is done in the right order. Here it isn't strictly necessary to include brackets since, when multiplying together a number of terms, the result is the same regardless of order. However, brackets do help to tidy things up and show which terms belong together.

Start the Windows calculator running on your computer (go to the Start menu and select Programs > Accessories > Calculator) then follow each step shown in the table below. (The > symbol represents the small black triangle shown on the right of a menu item, which indicates a sub-menu.)

| Step | Action | Calculator display |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Make sure the Windows calculator is in Scientific mode by selecting Scientific from the View menu. | 0. |

| 2 | Enter 3. | 3. |

| 3 | Click the Exp button which you will find in the left half of the calculator keyboard. ('Exp' stands for 'exponent'.) This tells the calculator that the next number you enter will be a power of 10 and that you are working in scientific notation. The 'e' now showing on the display indicates that the number you have entered is displayed in scientific notation. | 3.e + 0 |

| 4 | Enter 4. The display is now showing the equivalent of 3×104.You have now finished entering the term in the first set of brackets. | 3.e + 4 |

| 5 | Click the multiply (*) button. This tells the calculator that you want to multiply the number showing in the display by some other number. The display now changes to show the number you have entered in its full form (3×104= 30000). | 30000. |

| 6 | You will now start to enter the term in the second set of brackets. Enter 2. | 2. |

| 7 | Click the Exp button. | 2.e+0 |

| 8 | Enter 3. The display is now showing the equivalent of 2×103. You have now finished entering the term in the second set of brackets. | 2.e+3 |

| 9 | Click the equal (=) button. This tells the calculator that you want it to display the result of the calculation. This is shown in its full form. | 60000000. |

| 10 | Finally, you can force the calculator to display the result of the calculation in scientific notation. Do this by clicking the F-E button which you will find in the left half of the calculator keyboard. ('F-E' stands for 'fixed to exponent') The display is now showing the result in the 'shorthand' form which you can interpret as 6×107. | 6.e+7 |

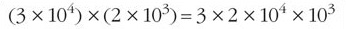

The result of the above exercise shows that (3×104)×(2×103)=6×107. Simple calculations like these can, in fact, be carried out quite easily without the need for a calculator, as we will explain below.

In calculations where terms are multiplied, the order of the terms isn't important and will not affect the result, so:

This image shows the following equation: open bracket, three times ten to the power of four, close bracket, times, open bracket, two times ten to the power of three, close bracket, equals three times two times ten to the power of four times ten to the power of thirty-one.

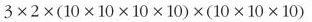

Writing this in full would give:

This image shows the following equation: three times two times, open bracket, ten times ten, times ten, times ten, close bracket, times, open bracket, ten times ten, times ten, close bracket.

Since:

This image shows the following equation: ten times ten, times ten, times ten, times ten, times ten, times ten equals ten to the power of seven.

we hope you can see that:

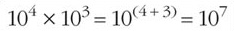

This image shows the following equation: ten to the power of four times ten to the power of three equals ten to the power of, open bracket, four plus three, close bracket, equals ten to the power of seven.

and therefore:

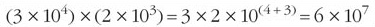

This image shows the following equation: open bracket, three times ten to the power of four, close bracket, times, open bracket, two times ten to the power of three, close bracket, equals three times two, times ten to the power of, open bracket, four plus three, close bracket, equals six times ten to the power of seven.

So when multiplying together two or more terms expressed in scientific notation, a shortcut to the result is to add the powers.

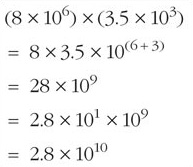

Sometimes the calculation will require a little more manipulation in order to express the result in scientific notation. For example:

This image shows the following equation, worked out over five lines: First line: open bracket, eight times ten to the power of six, close bracket, times, open bracket, three point five times ten to the power of three, close bracket. Second line: equals eight times three point five times ten to the power of, open bracket, six plus three, close bracket. Third line: equals twenty-eight times ten to the power of nine. Fourth line: two point eight times ten to the power of one, times ten to the power of nine. Fifth line: two point eight times ten to the power of ten.

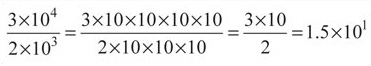

Similar principles can be used when dividing terms expressed in scientific notation. A shortcut to the result is to subtract the powers.

To demonstrate we'll evaluate (3×104) divided by (2×103):

This image shows the following fraction: three times ten to the power of four over two times ten to the power of three. The 10 in the denominator is crossed out. There is a gap, then the following fraction: three times ten, times ten, times ten, times ten over two times ten, times ten, times ten. Both numerator and denominator are followed by the equals sign, linking to the third fraction: three times ten over two. This is followed by the equation: one point five times ten to the power of one.

We hope you can see from this that:

This image shows the fraction: three times ten to the power of four over two times ten to the power of three. This is followed by the equation: three over two times ten to the power of open bracket four minus three, close bracket. The three in the four minus three is crossed out. Following this is the equation: one point five times ten to the power of one.

Activity 9: self-assessment

-

Use the 'short-cut' method to evaluate the following, write down your answers and then check your results using the Windows calculator.

-

(5×102)×(7×103)

-

-

-

Use the Windows calculator to evaluate the following, write down your answers correct to three significant figures.

-

(8.55×104)×(5.04×106)

-

(5.24×102)×(7.53×103)

-

Answer

Answers

-

3.5×106

-

2×103

-

4.31×1011

-

3.95×106

If any of your answers differ from ours, it is probably because you entered an incorrect value or clicked on the wrong key. If this happens, try the calculation again.

2.6 Modifying the medium to carry the message

Earlier we said that we can think of a signal as a deliberate variation in some property of the medium used to convey the data. Such variation needs to be done in a meaningful way. For example, think of the way pulses of light could be used to convey Morse code. (Morse code is a code in which letters and numbers are represented by groups of short dots and long dashes.) The light could be switched on and off so that a short light pulse could represent a dot and a longer pulse a dash. The same principle can be used with an electrical voltage applied to a copper wire. The sequence of on and off periods could be used to represent data, say, a stream of 1s and 0s. These can be detected and decoded at the receiving end in a communication system.

In radio signals, some property of the electromagnetic wave could be varied in a meaningful way – its frequency, for example. This is shown in Figure 7. Here we have indicated a number of equal time intervals. In the first interval, the wave completes three whole cycles, but during the second, third and fourth intervals, the wave completes only one and a half cycles per interval. So in these intervals the frequency of the wave is half the frequency of the first interval. Similarly, during periods 5, 6 and 8 the wave completes three whole cycles per interval, and only half that in intervals 7, 9 and 10. These changes of frequency can be detected and interpreted as data – say a 1 or a 0 depending on the frequency of wave during the measured interval.

Figure 7

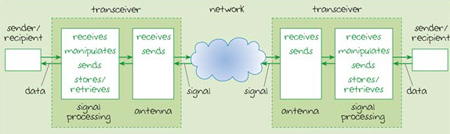

The electromagnetic wave can be described as a carrier because it carries the data. That is, some property has been modified to represent the data. The process of modifying the carrier in this way is called modulation. A transmitter takes the data from the sender, modifies the carrier, and then sends the resulting signal through the communication link. At the receiving end, a receiver takes the signal, and extracts the data by a process known as demodulation, then passes the data to the recipient. The process is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Figure 8 is in many ways similar to the diagrams used earlier in Figures 1 and 2, but it is slightly more abstract in some parts. For example, you are no longer shown, nor are named computing devices like a printer or computer. Instead the end points are rectangles labelled 'sender' and 'recipient'. These rectangles could be computers or printers, but could also be other devices. There may well be human users on the other side of them, but we are not concerned with those in this model so we have omitted them.

Another abstraction is the cloud that represents the network. This has also been done to simplify the diagram. We've chosen to focus on the parts that are most relevant to our discussion (which concerns the transmitter and receiver) and for this purpose we're not concerned with what is happening in the network links. The cloud indicates that there is something going on there but doesn't give any detail of what it is.

Notice in Figure 8 how we've shown the communication to be flowing in one direction only. This is because the transmitter receives data only from the sender and sends it only to the receiver. In this model there is no communication in the opposite direction. Some devices, known as transceivers, perform both the sending and receiving of signals so they could replace both the transmitter and receiver shown in the figure.

Activity 10: exploratory

How would you modify Figure 8 to model the use of transceivers in place of both the transmitter and receiver?

Discussion

The modifications needed would be:

-

the end points both become sender/recipient because both can send or receive;

-

the transmitter and receiver are both replaced by transceivers;

-

the arrows showing the communication flow now run in both directions.

These modifications are shown in Figure 9.

2.7 Propagation delay

The time taken for a signal to travel from its source to its destination is known as propagation delay. This is derived from the verb 'propagate' which in a physics context means 'spread' or 'travel'. The propagation delay depends on a number of factors, including the distance the signal has to travel and the signal's speed.

Contemporary physics states that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (or any electromagnetic wave) in a vacuum which, to the nearest metre, is 299 792 458 metres per second. This is a rather precise measurement and for most purposes we don't need to work to this degree of accuracy. You are more likely to see the speed of light given as 'approximately 3×108 m/s' (that is 300 000 000 metres per second). It's important to realise that not all carriers are able to achieve the speed of light. A voltage pulse travelling in a copper cable has a speed of approximately 2×108 m/s. Signals can also be delayed by the processes required to manipulate and manage them on their journey from sender to receiver.

It is often acceptable to round numbers up or down to make calculations simpler. The result won't be completely precise, but it will probably be close enough for many purposes. The box below takes the idea further and explains the principles.

Rounding numbers

The more digits there are in a number, the less contribution the digits at the right-hand end make to the magnitude of the number. Consider Table 2. Incrementing 9 by 1 results in an increase of the original number by almost one-tenth. Incrementing 99 by 1 results in an increase of the original number by almost one-hundredth, and so on. The longer the number, the less is the effect of an increase in the right-most digit. Or, put another way, the longer the number, the less significant the right-most digit becomes.

| Original number | New number | Fractional increase | Approximate fraction of original number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 10 | 1/9 | one-tenth |

| 99 | 100 | 1/99 | one-hundredth |

| 999 | 1 000 | 1/999 | one-thousandth |

| 9 999 | 10 000 | 1/9 999 | one ten-thousandth |

| 99 999 | 100 000 | 1/99 999 | one hundred-thousandth |

| 999 999 | 1 000 000 | 1/999 999 | one-millionth |

This means that in long numbers we can often disregard some of the digits at the right-hand end because they are not significant. Disregarding them will introduce very little error because they make very little contribution to the overall value. It is the digits at the left-hand end that are significant, and we can select the degree of accuracy required by choosing how many left-hand digits we consider to be significant for our purposes. We call these significant figures. Then we round the original number up or down until all but the required significant figures are shown as 0s.

For example, take the number 3482. Let's say we decide that we need to work with 3 significant figures. In this case we would round the original number down to 3480 because 3482 is closer to 3480 than it is to 3490.

Let's say instead that we decide to work with 2 significant figures. In this case I would round 3482 up to 3500 because 3482 is closer to 3500 than it is to 3400.

When we round a number up or down in this way it is important to indicate what we have done by stating that the rounded number is approximate, or by stating how many significant figures we are working to. Thus 3482 becomes:

3480 (correct to 3 significant figures)

or

3500 (correct to 2 significant figures)

These rules apply just the same when we are working with long numbers that include a decimal point, or with long numbers expressed in scientific notation. For example 2.14565879×108 would become 2.146×108 (correct to 4 significant figures), or 2.15×108 (correct to 3 significant figures).

The speed of light in a vacuum (299 792 458 m/s) gives a good example of why it can sometimes be useful to express how many significant figures we are working to. The figure becomes:

299 800 000 (correct to 4 significant figures)

and

300 000 000 (correct to 3 significant figures)

because the rounding (up in this case) gives a result that might otherwise be taken to be correct to only 1 significant figure.

2.8 Attenuation and distortion

As a signal travels from one device to another it has two problems to overcome. The first is that it gets weaker the further it travels, because some of its energy is absorbed by the transmission medium. This effect is known as attenuation. The extent of attenuation depends on the distance it has to travel and on the type of medium it is travelling through. An amplifier can be used to boost the signal power at the transmitter and receiver, and if necessary at various points in the transmission link, so that signal power can be maintained at a usable level.

The second problem is that the signal can become distorted by external influences as it travels along the communication path. This can be caused by other signals travelling in the vicinity, or by waves of energy such as solar energy, lightning, and pulses of energy from electrical machinery. You might have come across instances of distortion in your own domestic equipment. For example, I have a small TV in my bedroom and when I use my hairdryer nearby I can see spots and lines on the TV screen that are caused by the electromagnetic energy generated by the motor in the hairdryer. If I place my mobile phone next to my radio I often hear 'beeps' on my radio as the phone sends signals to the phone network.

Unless distortion can be removed from the signal at the receiving end then any amplification to overcome the problems of attenuation will also amplify any distortion in the received signal. Binary signals are quite resistant to distortion because they represent only two states that can usually be distinguished quite easily from any unwanted effects.

Activity 11: self-assessment

To test your understanding of what you have read so far about signals, try to write down answers to these questions.

-

The frequency of an electromagnetic wave is measured in units of __________

-

In what portion of the electromagnetic spectrum does an electromagnetic wave with a frequency of 108 Hz lie?

-

What is meant by the term 'modulation'?

-

Why might a signal become attenuated as it travels?

Answer

Answers

-

The frequency of an electromagnetic wave is measured in units of Hertz.

-

An electromagnetic wave with a frequency of 108 Hz lies within the band of frequencies known as radio waves.

-

'Modulation' is the term given to the process of modifying a carrier to represent data.

-

Energy from a signal is absorbed by the transmission medium. This weakens the signal.

3 Wired networks

3.1 Introduction

This section starts by broadly classifying different types of network, first by the nature of the communication links used to connect devices and then by a network's geographical spread. It then examines in more detail a network which uses a cabled communication link.

A networked device is often referred to as a node so we shall use this term in the sections that follow. A node is any device (for example, computer, printer, server) connected to a network, either as an end point (that is, a point where the communication link terminates) or some intermediary point (that is, a point which lies between end points on a communication link). To send data from one node to another there must be some kind of communication path between them. One option is for nodes to be physically linked to each other by a cable – for example, copper or fibre-optic cable. Each node must have a physical connection to the cable in order to send and receive data. Networks that use a physical communication link such as these are known as 'wired networks'. Wireless networks (which we shall discuss in the next section) have no physical connections between the nodes.

Networks can also be broadly classified according to their geographical spread: Local Area Networks (LANs) connect together a number of nodes within a single building or group of buildings situated close to each other. A LAN can connect together as few as two or three nodes or hundreds of nodes. You will also come across references to Personal Area Networks (PANs) which cover small areas such as a home, a single room within a home or even a car. A PAN is a type of LAN.

Wide Area Networks (WANs) connect together two or more LANs that are geographically separated. This is done by using links between LANs. A WAN could connect together all the LANs in offices of a national company and could even cross international boundaries.

This section will focus only on LANs. It will introduce you to the basic principles of operation of wired LANs, and in particular to a network technology known as Ethernet. Ethernet is the dominant technology used in LANs.

3.2 Wired networks – principles of operation

Each node in a network needs processes to control the flow of data over the network. These processes are carried out by a network interface card (NIC), which provides the interface between the node and the communication link. The NIC enables the physical connection to be made to the network.

Each node also needs a way of distinguishing it from all the other nodes on the network. This can be thought of as an address that other nodes use when they want to send data to a particular destination. Each node is assigned an identity number known as its Media Access Control (MAC) address.

Messages between nodes are not sent in one continuous stream but are broken up into small chunks called frames which are sent one at a time. Each frame includes some information which enables it to be routed through the network and delivered to the intended destination. All frames include the MAC address of both the destination node and the sending node. In some networks, frames are not routed specifically to the destination node but are sent to every node on the network. Each node reads the destination address and picks out those frames where the destination address matches its own.

As you learned in Section 2, the signals representing data get weaker the further they travel. This is one of the factors that could limit the maximum length of a communication link in a LAN. This limitation is overcome by the use of repeaters. A repeater increases the practical distance between nodes by regenerating the signal and passing it on.

3.3 Wired network configurations

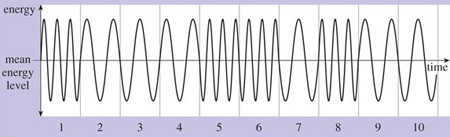

Network nodes can be connected together in different arrangements known as topologies. We are going to describe four common topologies that you may come across.

Figure 10

The simplest type is known as a bus topology. This is one where all the nodes connect to a single network cable and can communicate with every other attached node by placing a message onto the cable. A simplified representation of the layout of a bus topology is shown in Figure 10(a). To understand the diagram, imagine you are floating above the network and looking down. The circles represent the network nodes and the lines connecting them represent the communication links.

In a bus topology, each node connects to the same cable, so a frame sent by one node will arrive at every other node. Each node must read the destination MAC address in the frame to decide whether or not to accept it. If any node becomes inoperable, all the other nodes are still able to communicate with each other, but any cable failure will result in the loss of communication between nodes on opposite sides of the failure point.

In a star topology (Figure 10(b)) each node has its own cabled link to a central point called a hub. All messages are conveyed through the hub and, like the bus topology, will arrive at each node. In this arrangement, any single cable failure affects only one node, but a hub failure would make the entire network inoperable. Typically, the maximum number of nodes that can be connected together in a star topology is 24.

To expand a star network, hubs may be joined together so that nodes connected to one hub can communicate with nodes connected to another hub. This results in an extended star topology (Figure 10(c)).

Depending on the mode of operation, in some bus, star and extended star topologies, only one node at a time is allowed to place a frame onto the network. This means that every node has to compete with every other node for access to the network. As a network grows and traffic increases, a point is reached where competition becomes so great that the network becomes unacceptably slow.

A way of expanding the network to overcome the problems of competition is to stop sending all frames to every node and instead to separate the network into segments. A segment is a discrete portion of a network in which all nodes share the communication link. Segments are then joined together with a device known as a switch or bridge (Figure 10(d)). Such a device will examine each frame as it arrives and read the destination MAC address to establish whether or not to pass the frame onto an adjacent segment. A segment will receive only frames destined for nodes within it or frames that need to be routed through it to reach other segments further along the network. In some networks each segment could contain just a single node.

A mesh network has a web-like structure. In a full mesh topology (Figure 10(e)) each node has a point-to-point link with every other node. In a partial mesh topology (Figure 10(f)) some nodes have connections to a number of other nodes, but some may be connected to only one other node. Data between two nodes may have to travel through intermediary nodes before reaching its destination. In a partial mesh topology the nodes must have some knowledge of the network layout so that messages can be routed correctly. If a node or a communication link fails it is often possible to find another path to the destination, so mesh-type networks have high reliability.

Activity 12: self-assessment

To test your understanding of what you have read so far about wired networks, try to write down a short answer (a sentence or two) to these questions.

-

What is the term often used to describe devices connected to a wired network?

-

What is the purpose of the MAC address?

-

How does a repeater address the problem of attenuation?

-

How does a switch or a bridge make it possible to expand a network?

Answer

Answers

-

The term often used to describe devices connected to a wired network is 'node'.

-

Every node is assigned a MAC address. It is a number that uniquely identifies each node on a local area network.

-

A repeater takes a weak signal and regenerates it before passing it on.

-

A switch or bridge separates a network into segments and only passes on frames that are intended for an adjacent segment or that need to be routed through it. This means that nodes aren't competing with every other node for access to the network.

3.4 Protocols and standards

You have already met the idea of protocols in Section 1 – rules to govern how information is sent, transmitted and received. Protocols can be explained using an analogy with the way people talk to each other. When we talk we don't simply string words together in a random fashion: we have a set of rules (grammar) that determines the order of words and the way sentences are constructed. Understand didn't have other us difficult if it would be quite rules each these for to we. We hope the previous string of words illustrates what we mean! It's a jumbled-up version of the sentence 'If we didn't have these rules it would be quite difficult for us to understand each other.'

We also need to have a shared understanding of what a word means (for example, the word 'trunk' may have quite different meanings in North America and Britain). But we have thousands of versions of these rules – different languages and dialects – so simply having a set of rules isn't enough to ensure good communication. We have to agree to use the same rules (or at least nearly the same rules) or have some mechanism to translate from one set of rules to another.

Fortunately a number of organisations have taken responsibility for ensuring that particular communication protocols are clearly stated, recorded and made available to others. These organisations agree on and produce the necessary standards, which are a kind of technical specification that sets out the rules and requirements to ensure interoperability. A standards document is drawn up with the involvement and agreement of all interested parties, for example representatives of users, manufacturers and government agencies. The dominant standard in wired LANs is one that is commonly known as Ethernet.

3.5 Establishing Ethernet standards

The first Ethernet network was developed in the early 1970s, long before the days of the World Wide Web and personal computers (PCs). It was designed by researchers at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Centre in California, USA to connect the Centre's 'Alto' computers to an office printer.

Ethernet's journey from its modest roots to become the dominant network technology is a fascinating one. One of the main reasons for its success lies with the decision to publish the standard. Standards that are available to anyone in this way are known as open standards.

Activity 13: exploratory

Try to think of a standardised product that you use in your own home. Make some notes about what features of the product are standardised. Why do you think that the availability of open standards helps to establish related products in the marketplace?

Discussion

One simple example of a standardised product that I thought of is the plug that connects my domestic electrical equipment (such as my kettle, hairdryer, table lamps) to the mains electricity supply. In the UK, these plugs have three pins and conform to a standard known as BS1363. BS stands for 'British Standard' and indicates that the standard has been agreed by the British Standards Institute – the national standards body of the UK. BS1363 specifies things like the shape and configuration of the pins, the type of material various parts of the plug should be manufactured from, and the safety features it should possess. Other countries use different standards for their electrical plugs and sockets, so when I travel abroad I generally need an adaptor to use the electrical equipment I take with me.

When a standard is widely available, many different manufacturers are able to produce products that are compatible. This is likely to increase competition and drive down the costs to consumers. It is also likely to increase manufacturers' confidence in the market and so encourages them to invest in and develop products. This in turn is likely to lead to greater reliability.

The standardising body for Ethernet is The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). (You may remember that the article in Section 1, Networked microsensors and the end of the world as we know it, was published by the IEEE.)

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

The IEEE was formed from two earlier organisations: the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) and the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE). As technology developed, the boundaries between these two organisations became more and more blurred and eventually, in 1963, they merged. The IEEE is based in the USA but is essentially a global association of professionals working in technical areas such as computing, telecommunications, power engineering and electronics.

When developing standards, it is usual for the IEEE to establish a committee of interested bodies. This committee forms a working group to collaborate and agree on the details of the proposed standard. The working group set up to standardise network technologies took its name from the month and year (February 1980) of its formation, and became known as the '802 working group'. Task forces appointed to work on particular aspects of networking are each identified by a further number. The Ethernet taskforce and Ethernet standards are all identified by IEEE 802.3.

The IEEE 802.3 standard specifies a total data rate of 10 Mbps, but subsequent developments in technology enable faster data rates to be achieved and so new 802.3 standards have been defined, providing data rates of 100 Mbps, 1 Gbps (gigabits per second) or 10 Gbps. These new standards are identified by adding a suffix to the standard number so, for example, the 10 Gbps Ethernet standard is known as IEEE 802.3ae.

I find that it's quite difficult to get a feel for the magnitude of data rates like those I quoted in the previous paragraph. When I meet a very large number, I find it is helpful to compare it with something relevant that I do have a 'feel' for (for example, something I'm familiar with in everyday life). It doesn't have to be an exact comparison – just an estimate helps. The next activity will give you an example of a simple comparison you could make.

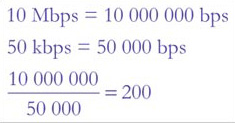

Activity 14: exploratory

Estimate how many times faster the data rate of the original Ethernet standard (10 Mbps) is, compared to the data rate of a modern standard dial-up modem of 56 kbps. (Hint: round down the dial-up modem rate to 50 kbps.)

Discussion

We suggested you round down the dial-up modem rate to 50 kbps becomes it then becomes a much easier figure to work with, so this speeds up the calculations. Because only an estimate is required, you don't need to come up with an exact answer, just one that will help you to make a rough comparison.

First we need to express both figures in the same units. Currently one is expressed as Mbps and the other as kbps, so we will express them both in bps.

This image shows information over the three lines. First line: ten megabits per second. This is followed by ten million bits per second. Second line: fifty kilobytes per second. This is followed by fifty thousand bits per second. Third line: the fraction ten million over fifty thousand equals two hundred.

So the first commercial Ethernet network was about 200 times faster than a modern 56 kbps modem dial-up connection.

Comparisons and estimates are two very useful tools. A comparison with something you are already familiar with can help you to get a feel for new ideas or concepts. (For example, I can get a feel for the size of a hectare once I know it is about the same size as a soccer pitch of international standard.) As well as providing a quick way of making comparisons, estimates can also be useful in checking that the answers you come up with for calculations are sensible.

3.6 Routers

One type of network device we haven't mentioned is a router. This is because a router generally works at the edge of a LAN rather than within it. A router can operate at a level that is independent of specific LAN protocols so it can be used to join an Ethernet LAN with a LAN that uses different protocols. A router holds information about the structure of a network and can make decisions about how data should be routed through it. As well as being used to connect together different types of LAN, a router connects different types of network. For example, a router would be used to connect a LAN to a WAN.

4 Wireless networks

4.1 Introduction

The focus of Section 3 was on LANs that use some kind of physical medium (for example, copper wires or fibre-optic cables) to connect together network nodes. In this section we'll be examining wireless networks – that is, networks that transmit data through the air (or space) using radio waves.

There's nothing new about wireless: the principles of transmitting information using radio waves were discovered over a century ago. However, using radio waves to provide the transmission links in a network is a relatively new and fast-growing technology. It enables us to connect into networks in public places like airports and city centres without needing a wired link.

You may already know a little about using radio waves to connect into a network. You may have heard or read news reports that discuss wireless networks. You may even have some experience of using them yourself. If you use a mobile phone, Bluetooth®-enabled device, or connect your computer to a network using WiFi, then your communications will be using radio waves.

In this and the next section we shall be outlining some of the principles of wireless transmission and then looking in more detail at two particular wireless standards – WiFi and Bluetooth. We'll also be discussing some of the issues arising from the deployment of wireless networks

Activity 15: exploratory

-

Spend a short time – not more than 3 or 4 minutes – jotting down some notes on what you know about how wireless networks operate. (If you don't know anything about wireless networks yet, just move on to the next part of the activity.)

-

Based on what you have learned about wired LANs in Section 3, jot down a few things you would like to know about wireless networks.

Discussion

Of course, we can't guess what you already know or would like to know. Your notes might be about what equipment is needed, what data rates are possible, whether there is a limit on the distance between nodes or a limit on the number of nodes a wireless network can support. Or they might be something different.

The value in this activity is that you have thought about two important questions: 'What do I already know about this topic?' and 'What further things would I like to know about this topic?' Many people find that this sort of approach helps them to become more active in their learning because it gives them a focus and helps them to engage more effectively with the topic. See if it works for you.

4.2 Basic principles of wireless transmission

I've never quite lost the sense of wonder at the way information can be transmitted with no visible link between the sender and recipient. When I was a child I used to think that sound came through the wire linking my family's radio to the mains electricity supply (I was born before the days of battery-powered transistor radios) and I couldn't understand why my parents referred to it as 'the wireless' – since clearly it wasn't. I now know that the wire simply fed the radio with the electrical power it needed. The radio signals were picked up by a special electrical conductor called an antenna. (Another name for antenna is aerial and you are likely to see these terms used interchangeably, both within this course and elsewhere.)

Radio signals arrive through the air as fluctuations in the electromagnetic field of a radio wave. This induces a fluctuating electrical current to flow in the antenna. These fluctuations are detected and translated into data. But an antenna can be used in two different ways. Fluctuations in electrical current flowing in an antenna can also emit a radio signal, so an antenna can be used to both receive and send radio signals. Most devices operating in radio networks are transceivers (that is, they can both send and receive radio signals) and will use the same antenna when sending and receiving. Figure 8 (Section 2) can be developed to represent a wireless network. This is shown in Figure 11 where we have broken down the components within the radio transceiver to show the antenna and the signal processing components.

Figure 11

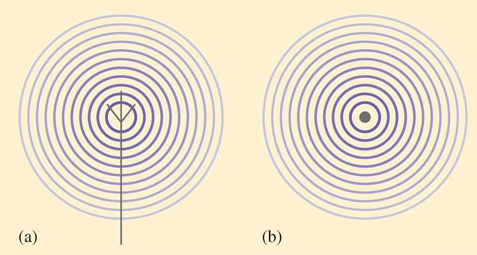

When signals are travelling in cables, they follow the path of the cable, even though this may twist and turn. For this reason, cables are described as 'guided' media. Radio signals are not guided in this way. The electromagnetic waves carrying the signal can propagate in all directions, and may spread out in a spherical pattern as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12

The term 'wavefront' refers to all points on a wave that are equidistant from its source. In this case, the wavefronts are represented by the concentric circles in both figures. Notice how the circles become fainter with distance from the centre, representing the way the signal weakens. Figure 12(a) shows a representation of a side view of an antenna. In practice antennas come in many shapes and sizes, but this representation is often used in diagrams regardless of the actual design of the antenna. In Figure 12(b) we have shown a representation looking down onto the antenna.

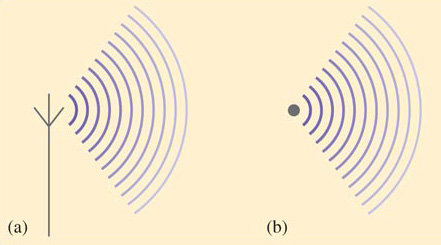

Antennas can be designed to be directional so that the signal power is directed into a beam (Figure 13). This allows the signal to travel further for the same power. However, in general, the attenuation of a radio signal is greater than the attenuation of a signal travelling an equivalent distance via a cable.

Figure 13

The maximum practical distance that a signal can be propagated is influenced by factors such as the signal frequency and strength, the physical environment and the design of the antenna. Low-frequency waves can travel further than high-frequency waves. Low-frequency waves are also more efficient at penetrating physical barriers such as walls and floors – something that high-frequency waves, like visible light, can't do. So it is the waves at the lower frequency end of the electromagnetic spectrum that are used for over-the-air communications. These include the radio and microwave frequencies.

Activity 16: self-assessment

Refer back to Figure 6 in Section 2. Approximately what section of the electromagnetic spectrum is occupied by radio waves? (That is, at approximately what frequency do they start and at approximately what frequency do they finish?)

Answer

Radio waves occupy the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum lying between about 103 Hz (1 kHz) and 1010 Hz (10 GHz).

From the answer to Activity 16, we can calculate the approximate frequency range of radio waves. This is the difference between the highest and lowest frequencies in that section which, in this case, is somewhere around 1010 Hz minus 103 Hz (10 000 000 000 Hz minus 1 000 Hz). If we were to calculate an answer from these figures the result would be 9 999 999 000 Hz or approximately 1010 Hz.

You may have been surprised to find that the result of deducting 1 000 Hz (1 kHz) from 10 000 000 000 Hz (10 GHz) gave an approximate result of 10 000 000 000 (10 GHz). After all, we have taken something away from the original 10 GHz, so how can the answer be approximately the same as the figure we started with? This is because 10 GHz is extremely large compared to 1 kHz – in fact 10 million (107) times greater. So subtracting 1 kHz is insignificant.

4.3 Regulation

Increasing demand for wireless technology means that the radio frequencies must be carefully managed and allocated by governments to satisfy all the different users and to prevent interference between them. (You may remember the UK Government's auction of 3G radio licences in Spring 2000 which raised approximately £22.5 billion.)

Before transmitting radio signals, organisations must usually obtain a licence permitting them to use a specified frequency or band of frequencies. However, one band of radio frequencies is available internationally for unlicensed users. These are the frequencies lying between 2.4000 GHz and 2.4835 GHz. These frequencies – usually referred to simply as the 2.4 GHz frequency band – are collectively known as the industrial, scientific and medical (ISM) radio band. (Some countries also allocate additional frequencies for unlicensed users.)

In the remainder of this section we introduce two wireless standards that are designed to operate within the ISM band of radio frequencies. These are WiFi, developed by The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and covered by the IEEE 802.11 family of wireless LAN standards, and Bluetooth, developed by the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG) and covered by the IEEE 802.15 family of wireless PAN standards.

4.4 An introduction to WiFi

WiFi (from 'Wireless Fidelity') is used to connect devices together in one of two network configurations known as 'ad hoc' and 'infrastructure'. We shall explain these terms shortly. (As a starting point, though, you could look up the terms 'ad hoc' and 'infrastructure' in your dictionary.)

In wireless LANs, nodes are usually referred to as stations – probably because each communicating device acts as a radio station with transmitter and receiver. These functions, and the necessary control functions, are provided by a wireless network interface card (wireless NIC) in a similar way to wired networks.

4.5 WiFi network structure

A WiFi network can operate in one of two different modes: ad hoc mode or infrastructure mode

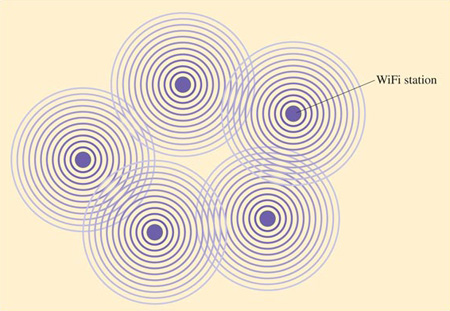

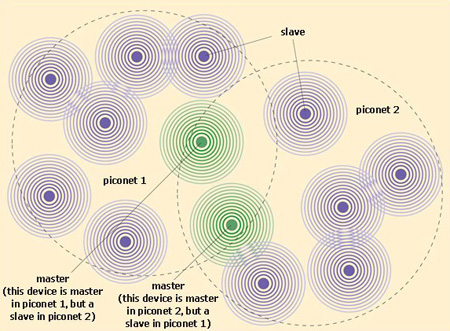

In an ad hoc network, stations communicate with each other directly, without the need for any intermediary or central control. This means that when one WiFi device comes within range of another, a direct communication channel can be set up between them. This is known as peer-to-peer communication. Additional devices can join the network, all communicating with each other in a broadcast fashion. (In this context, 'broadcast' means that a message sent by one node will arrive at every other node in the network, regardless of the destination address.)

Figure 14 provides a diagram of a possible geographical layout of an ad hoc network. This figure is similar to the diagrams of network topologies you met in Section 3.3, in that it is a representation of a network layout viewed as though you were floating above it and looking down. In Figure 14, the dark circles represent WiFi stations. The concentric circles around them show that the communication channel is radio waves. In this case, the diagram indicates non-directional antennas. However, since the focus of this diagram is the network layout, then the detail of whether directional or non-directional antennas are used isn't important.

Figure 14

An ad hoc network is likely to be temporary – for example, a network set up for a business meeting where people want to share information stored on portable devices like lap-top computers and personal digital assistants (PDAs). (If you looked up the term 'ad hoc' in your dictionary you probably found a definition something like 'for a specific purpose, impromptu, not pre-planned'.) An ad hoc network is independent of, and isolated from, any other network.

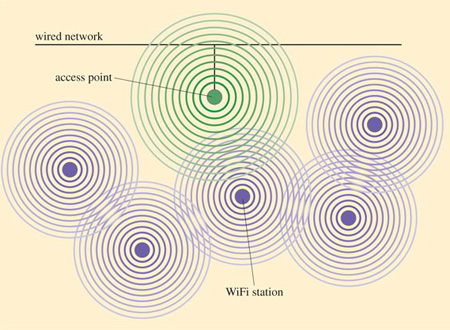

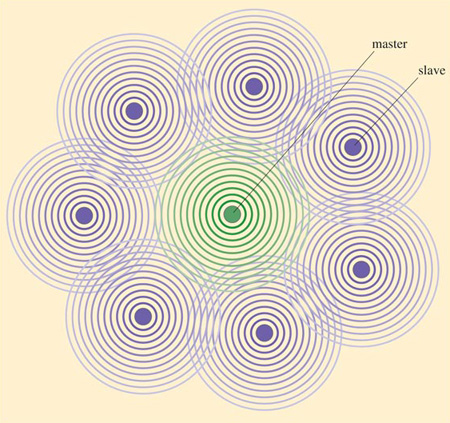

In infrastructure mode (Figure 15), stations communicate with each other via a wireless access point (AP) which also acts as a connector between a wired network and the wireless network. The access point is effectively a base station that controls the communication between the other stations. Access points form part of a wired network infrastructure and are not mobile. (If you looked up the word 'infrastructure' in your dictionary the definition given probably used terms like 'underlying foundation, basic structure, substructure'.)

4.6 WiFi stations

A WiFi station determines whether it is in range of an AP by transmitting an enquiry, known as a probe request frame, and waiting for a response. If more than one AP responds, the station will choose to communicate with the one that has the strongest signal. A probe request frame initiates the WiFi connection and is an example of a management frame – a type of frame that does not carry any message data.

Just like the nodes on an Ethernet network, each station must have a means of being uniquely identified by a MAC address. Every message data frame sent must contain the MAC address of the source, destination and access point, as well as other management data that enables the frames to be correctly sequenced and errors to be detected.

Because all the stations in a WiFi network share the same communication channel, only one station at a time can be allowed to send data. So a station waits until it detects a period of inactivity and then uses a special protocol which prevents two or more stations sending data at exactly the same time. The exchanges involved in these protocols are another example of management data.

The WiFi standards do not define any upper limit on the number of stations that can join a network, though some particular equipment manufacturers may specify a limit. (We've seen one which stipulates a maximum of 128 stations connected to any one AP.) However, as the number of communicating stations increases, the channel capacity available for each station decreases. A point will eventually be reached when the network becomes too congested to provide an adequate service.

4.7 WiFi data rates and operating range

Just as for Ethernet, developments in technology have increased the achievable data rates since the first WiFi standard was developed in 1997. At the time of writing, the latest WiFi standard to be published – IEEE 802.11g – defines a data rate of 54 Mbps.

Activity 17: exploratory

How do you think the rate for transmitting messages between stations is affected by:

-

the management information that is included with each frame;

-

the protocols used to enable multiple stations to share the communication channel;

-

multiple users on a WiFi network?

Discussion

Both the management information and the sharing protocols impose an overhead that uses up some of the capacity of the communication channel. This effectively reduces the capacity available for sending message data (as compared to management data). The effective data rate will, therefore, be lower than the value quoted.

When thinking about the effects of multiple users on the network, it's also important to realise that the data rate quoted is the maximum that can be achieved, and this has to be shared out between all the users of the network. As the number of users increases, the data rate available to each individual user decreases.

The practical message data rate that can be achieved in a wireless network is often described as its throughput. Even in ideal operating conditions, the throughput may be only 50 per cent to 75 per cent of the maximum data rate. For WiFi, throughput is generally about half the maximum data rate possible on the communication channel, giving about 30 Mbps for 802.11g networks, and this has to be shared between all the stations on the network.

The achievable data rate reduces with distance from the AP (or in the case of an ad hoc network, with distance from other stations). Maximum data rates can be achieved only within about 30 m of an AP, tailing off at distances greater than this. For 802.11g networks the data rate drops to as low as 1 or 2 Mbps at 100 m. Physical barriers such as partitions and walls will further reduce the maximum rate possible at a given distance from the AP.

4.8 WiFi – a summary

Activity 18: self-assessment

To test your understanding of what you have read so far about WiFi, say whether each of the statements below is true or false.

-

In ad hoc mode, WiFi stations are connected to a wired network via an access point.

-

All stations connected to a WiFi network in infrastructure mode will be able to achieve identical data rates.

-

Every WiFi station requires a MAC address.

-

Throughput is a term that describes the maximum data rate of a WiFi network.

Answer

Answers

-

The statement is false. In ad hoc mode, the WiFi network is isolated from any other network.

-

The statement is false. Data rate is affected by distance from the AP and the presence of any physical barriers, so stations connected to a WiFi infrastructure network are likely to achieve different data rates.

-

The statement is true. Every WiFi station requires a MAC address so that it can be uniquely identified within the network.

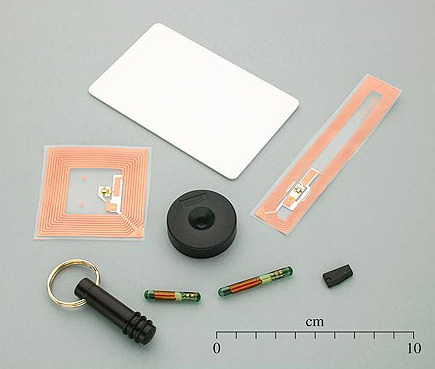

-