Week 3: Double-entry accounting

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 5:39 PM

Week 3: Double-entry accounting

Introduction

As you learned in Week 1, accounting is a process that involves:

- the systematic recording of all relevant financial transactions and events

- classifying, interpreting, summarising and reporting such bookkeeping data

- the production of useful information from that data and its presentation to stakeholders of a business such as owners, lenders and the tax office.

In today’s electronically enabled business world most organisations produce their financial accounts using a computer program known as an accounting package. Such accounting software produces, at the click of a button, all the reports needed from the initial recording of transactions. Understanding and using these accounting packages properly requires a deep understanding of all the accounting knowledge studied in this course. Accountants do not just accept what the computer produces; they have to understand what these packages are telling them. Therefore, as students of accounting, you have to understand the rules of double-entry accounting that will be explained this week. Before learning these rules, you need to understand the fundamental accounting concepts that support the activity of double-entry accounting. Gaining knowledge of such fundamental concepts is the first aim of your learning this week.

3.1 The essential concepts behind double-entry accounting

Three concepts of accounting form the basis of the double-entry bookkeeping system of recording transactions and preparing financial accounts:

The business entity concept:

The business entity concept states that a business is separate from the owner(s) of the business. You were introduced to this concept in Week 1.

The accounting equation:

The accounting equation, for any business, states: Assets = Capital + Liabilities. You were introduced to the equation in Week 2.

The duality concept:

The duality concept means that every transaction has two effects. This is a core concept you will learn about this week.

3.1.1 The business entity concept

The business entity concept states that the business is separate from the owner(s) of the business. Therefore the accounting records for even the simplest business, the sole trader, must be kept separate from the personal affairs of the owner or owners.

There are basically three types of business entity:

- sole trader

- partnership

- limited company.

The principles of double-entry accounting apply to all forms of business organisation, as well as not-for-profit organisations.

As you learned in Week 1, any business starts with no money. It needs resources to be able to operate and those resources have to be financed. Right from the start it often also needs to incur debts or liabilities to buy assets such as equipment and inventory that it will use for future financial benefit. Assets, capital and liabilities are the elements of the accounting equation, which expresses the relation between these elements.

3.1.2 The accounting equation

The financial position of a business is expressed in the statement of financial position, which is more commonly called the balance sheet. The financial position of a business is represented by:

- assets (what the business owns)

- liabilities (what the business owes)

- owner’s capital (the monetary value of the owner’s investment in the business).

As you may remember from Week 2, the accounting equation (also called balance sheet equation), for any business, says:

| Assets = Capital + Liabilities |

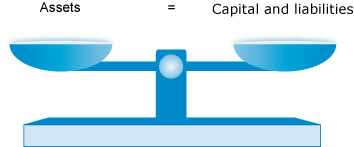

Figure 1 below demonstrates the accounting equation.

This diagram illustrates the concept of the accounting equation.

There is a picture of a set of scales with both sides balanced. The left arm of the scales contains assets. This is balanced by the right arm of the scales, which contains capital and liabilities.

The accounting equation should be kept in balance at all times i.e. the assets on the left side of the equal sign should always be the same as the sum of the capital and liabilities on the right-hand side.

Activity 1 The relationship between assets, liabilities and capital

A business at the end of its first year of trading has assets of £10,000 and liabilities of £8,000.

- What is the capital position of the business at the end of its first year?

Answer

£2,000

Show the position of the business according to the accounting equation.

Answer

Assets of £10,000 = Capital of £2,000 + Liabilities of £8,000

Any change in assets, capital or liabilities in the business has to keep the accounting equation in balance. If, for example, the business buys goods for sale for £200 on credit from a supplier then the accounting equation will look as follows:

Assets of £10,000 + £200 (new asset) = Capital of £2,000 + Liabilities of £8,000 + £200 (new liability)

or £10,200 = £2,000 + £8,200

This increase in both assets and liabilities in this example is known as the dual effect of every transaction. The next activity will help you to understand this better.

Activity 2 The dual effect of any transaction

A business buys a printer for £80 from the cash it keeps available for all expenditure under £100.

- What is the dual effect of this transaction?

Answer

The asset printer increases by £80 and the asset cash decreases by £80.

- What is the effect on the accounting equation of this transaction?

Answer

The accounting equation of the business will stay the same as the figure for assets will stay the same i.e. £80 - £80 = £0.

In the next section, the dual effect – also known as the duality principle – of every transaction will be looked at in more detail.

3.1.3 The duality principle in practice

Whether a business does one transaction or a thousand, the same results of the accounting equation and the duality principle are achieved.

- Each transaction will have two effects in order that the accounting equation is kept in balance.

- Assets or liabilities can further be broken down into the type of asset or liability that is affected.

- For each transaction, as well as for the overall effect of a number of transactions, the figure for capital will reflect the accounting equation: A = C + L.

The next activity should help you to understand how to apply the accounting equation and the duality principle over a number of different transactions.

Activity 3 The accounting equation in practice

Edgar Edwards sets up a small sole trader business as Edgar Edwards Enterprises on 1 July in the year 20X2.

Complete the table below, in which the first six transactions of the business are listed in the left-most column. The effect of the first three transactions, as well as the overall effect of all six transactions, has been completed for you to show you the accounting equation always balances.

Table 2 Completion of double-entry transactions

Answer

| Transactions | Effect on A = C + L | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assets = £ |

Capital £ |

+ Liabilities £ |

|

| 1. The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on the 1 July 20X2. | +5,000 (bank) |

+5,000 | 0 |

| 2. The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on the 2 July 20X2. | +400 (furniture) |

0 | +400 (payables: Pearl Ltd) |

| 3. The business buys a computer for £600 on the 3 July 20X2. | +600 (computer) –600 (bank) |

0 | 0 |

| 4. The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on the 4 July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account. | +5,000 (bank) |

0 | +5,000 (loan) |

| 5. The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 on the 5 July 20X2. | –200 (bank) |

0 | –200 (payables: Pearl Ltd) |

| 6. The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on the 6 July 20X2. | –50 (bank) |

–50 | 0 |

| Summary (overall effect) | +10,150 | +4,950 | +5,200 |

After these six transactions the accounting equation becomes:

| Assets = Capital + Liabilities |

| £10,150 = £4,950 + £5,200 |

The accounting equation remains in balance as every transaction must alter both sides of the equation, A = C + L, by the same amount as a result of the duality principle.

This fact that every transaction has a dual effect on the accounting equation is the basis of the double-entry system of recording transactions.

3.2 The system of double-entry accounting

Rather than keep changing the accounting equation as in Activity 3, every transaction is recorded using an established double-entry system. This system uses pages ruled off in the form of a T, known as T-account, as illustrated below.

The following T-accounts that you will encounter in Weeks 3 and 4 of this course are available to download in a Word document: T-accounts.

These T–accounts are more correctly known as ‘ledger accounts’ as they were originally recorded in a ledger, the old name for a book. Under this system every transaction has two separate and distinct aspects, so two separate T-accounts are involved in each transaction. Monetary values recorded in these T-accounts are recorded either on the left-hand side, known as the debit side, or on the right-hand side known as the credit side. The value of the debits should always equal the values of the credits, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Separate T-accounts are needed for each type of asset and liability and also for capital. At least two accounts are needed to record each transaction.

This diagram illustrates the concept double entry.

There is a picture of a set of scales with both sides balanced. The left arm of the scales contains debit. This is balanced by the right arm of the scales, which contains credit.

Box 1 The difference between debit and credit and debtors and creditors

The term debit has nothing to do with debtors, the amount owing to a business by its credit customers. A debit in a T-account simply means that it is recorded on the left side of such an account. The term credit has nothing to do with creditors, the amount owing to a business by its credit suppliers. A credit in a T-account simply means that it is recorded on the right side of such an account.

3.2.1 Following the double-entry rules

The following example shows how T-accounts work to record a transaction as a double entry.

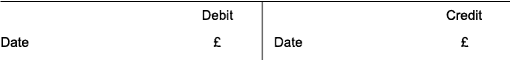

On 1 June 20X5 a business purchases a computer for £7,000 on credit from a supplier, Jones Limited.

According to the duality principle both the computer account (an asset account) and the Jones Limited account (a liability account) will be increased by £7,000 to reflect the credit purchase.

The transaction is recorded in the two separate T-accounts according to certain steps and rules that apply to every transaction.

For every transaction you need to follow three steps:

Step 1: Identify the two accounts affected.

Step 2: Decide the effect on each account. Perhaps one account is increasing and one is decreasing, or both accounts are increasing, or decreasing. (This ensures that that accounting equation A = C + L is always kept in balance after every transaction.)

Step 3: Record the entries.

If a transaction increases an asset account, then the value of this increase must be recorded on the debit or left side of the asset account. If, however, a transaction decreases an asset account, then the value of this decrease must be recorded on the credit or right side of the asset account. The converse of these rules applies to liability accounts and the capital account. These rules are summarised below and should be memorised.

| Account name | Effect of transaction | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset | Increase | Debit | |

| Decrease | Credit | ||

| Liability | Increase | Credit | |

| Decrease | Debit | ||

| Capital | Increase | Credit | |

| Decrease | Debit |

Box 2 Stop and reflect

Why do you think the rules of double entry must be memorised?

These rules of double-entry accounting must be memorised as they form the basis of further work in this course as well any further study you do in accounting. The best way to remember them and to see how they work is to work through the following example and activity, so that double entry slowly becomes second nature to you.

In our example below, and according to the double-entry rules, the increase to the asset account ‘Computer’ must show a debit of £7,000, while the increase to the liability account ‘Jones Limited’ must show a credit of £7,000.

Each T-account, when recording a transaction, names the corresponding T-account to show that the transaction reflects a double entry. So, in the computer account the £7,000 debit is described as ‘Jones Limited’, and in the Jones Limited account the £7,000 credit is described as ‘Computer’.

Box 3 The reason why your bank account says your positive bank balance is a credit

When you have money in the bank, the bank statement shows that your account has a credit balance. This is because when the bank receives money from you they credit your account in their books as your deposit is a liability to them. If you tell them to pay your money to someone else (perhaps a mortgage payment or a mobile phone bill) the bank will have effectively given the money back to you and so the bank will debit your account. According to the same rules of double entry, if you have your own bank account, your deposit will be an asset in your books and thus a debit in your bank account. Any payment from this asset account will thus be a credit entry to show that the asset has decreased in value. Always remember that the bank’s records are a mirror image of your own as your deposit is a liability to them but an asset to you.

3.2.2 Recording transactions using T-accounts

The following activity, which revisits the transactions in Activity 3, illustrates these double-entry rules for asset and liability accounts as well as the capital account. In this activity you will not enter the answer in a box but will instead have an opportunity to work out the answer mentally before you click on the ‘Reveal answer’ button.

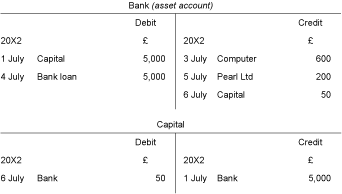

Activity 4 Recording transactions in double entry

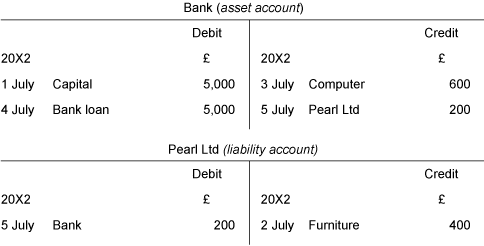

As per Activity 3, Edgar Edwards Enterprises carries out the following six transactions:

- The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2.

- The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2.

- The business buys a computer for £600 on 3 July 20X2 from the bank account.

- The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4 July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account.

- The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 on 5 July 20X2.

- The owner takes £50 from the bank for personal spending on 6 July 20X2.

For each of the transactions above you will be given the two relevant ledger or T-accounts, and you will need to decide the date, corresponding account and the relevant amount in either the debit or credit side of the account. Go back over the rules of double-entry accounting and the layout of T-accounts if you have forgotten them.

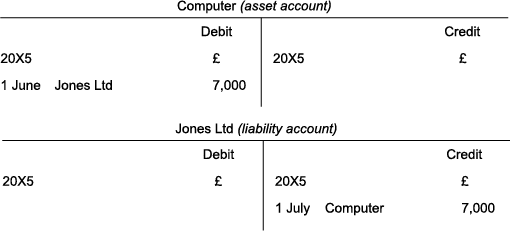

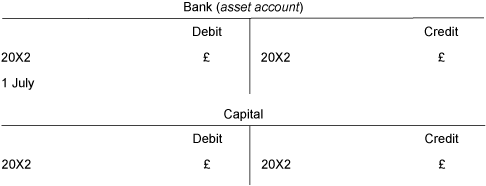

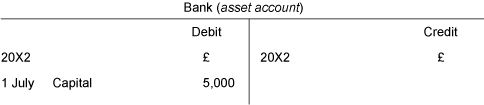

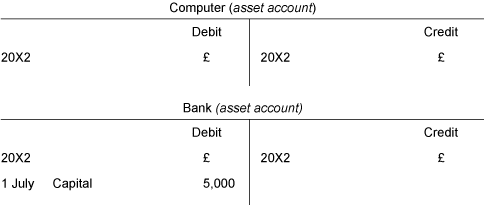

Transaction 1: The owner starts the business with £5,000 paid into a business bank account on 1 July 20X2

Answer

Receipt of money of £5,000 into the bank account is recorded on the debit side of the bank account as the asset of money into the bank has increased.

The capital account is recorded on the credit side to indicate that capital has increased.

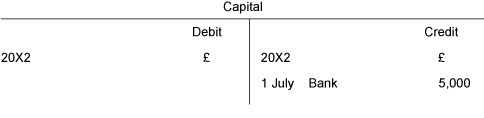

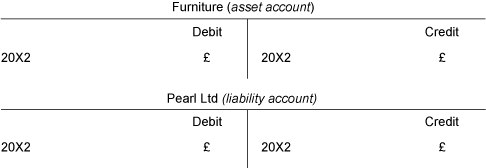

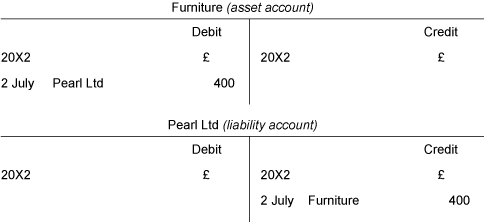

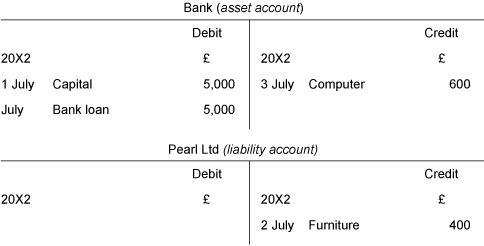

Transaction 2: The business buys furniture for £400 on credit from Pearl Ltd on 2 July 20X2.

Answer

According to the rules of double-entry accounting debit the asset account and credit the liability account.

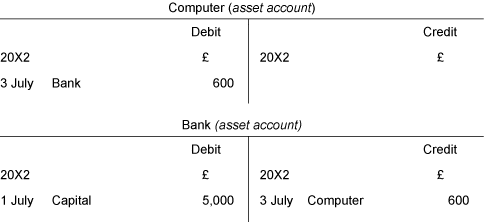

Transaction 3: The business buys a computer for £600 on 3 July 20X2.

Answer

According to the rules of double-entry accounting debit the first asset account ‘Computer’ to show an increase and credit the second asset account ‘Bank’ to show a decrease.

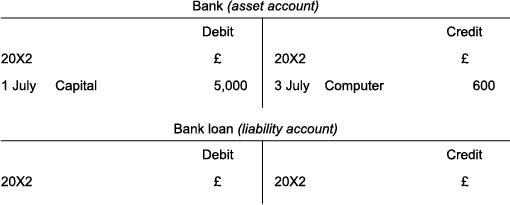

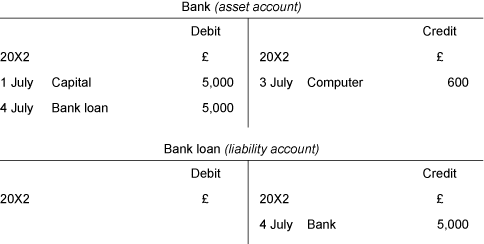

Transaction 4: The business borrows £5,000 on loan from a bank on 4 July 20X2. The money is paid into the business bank account.

Answer

According to the rules of double-entry accounting debit the asset account ‘Bank’ and credit the liability account ‘Bank loan’.

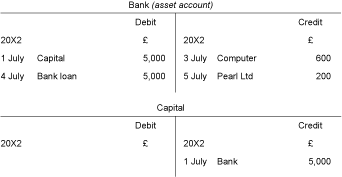

Transaction 5: The business pays Pearl Ltd £200 on 5 July 20X2.

Answer

According to the rules of double-entry accounting debit the liability account and credit the asset account.

In the next and final week you will learn how to work out the balance for each account in order to prepare the trial balance and the balance sheet. As you can see in the bank account above, there may be a number of changes in an account for a period and it is important to know the balance in such an account at the end of a period.

Summary of Week 3

The three concepts that form the basis of double-entry accounting are the business entity concept, the accounting equation and the duality concept. The business entity concept means that a business is separate from the owner(s) of the business. The accounting equation for any business states that Assets = Capital + Liabilities. The duality concept means that every transaction has two effects.

The basic principle of double-entry accounting is for every transaction recorded there should be a debit entry and a credit entry in the relevant T-accounts according to the following double-entry rules:

| Account name | Effect of transaction | Debit | Credit |

| Asset | Increase | Debit | |

| Decrease | Credit | ||

| Liability | Increase | Credit | |

| Decrease | Debit | ||

| Capital | Increase | Credit | |

| Decrease | Debit |

You can now go to Week 4: Preparing the trial balance and the balance sheet.

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Jonathan Winship.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2015 The Open University