Exploring equality and equity in education

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 8 May 2024, 3:24 AM

Exploring equality and equity in education

Introduction

In this free course, Exploring equality and equity in education, you will explore your experiences and thoughts on equality and equity in education and be introduced to different understandings of these concepts. You will start to look at some of the influences on equality which are common across the world and individuals’ interpretations of inequality within their social worlds.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course EE814 Addressing inequality and difference in educational practice.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

delineate different understandings of equality in education

give some examples of inequalities in different cultures and jurisdictions.

1 Equality and you

Across jurisdictions and cultures, there are different policies and practices which result in some people finding it difficult to gain access to education – for example, education may be available in urban areas but not in rural ones, male learners may have priority over female learners, universal education may be limited to primary phase, religious tenets may preclude some learners from participating in education, families in poverty may not be able to have a child in school rather than in labour.

All nations demonstrate some inequality in the quality of life enjoyed by citizens and struggles for equality and justice are widely experienced across the world. A central theme to your study in this course is the idea of ‘equality’ and how we consider achieving ‘equity’ in education and what this means to different people in different places and at different times. Notions of equality in education are not fixed but shift over time and place. The particular meaning ascribed to the concept of equality and how equity can be achieved will be influenced by people’s ideas on the purpose of education, their political priorities and values, expectations from parents, students and other stakeholders in the community or landscape in which they live and practise and prevailing policy frameworks. Thus, your own understanding of what constitutes, creates and perpetuates inequality in education will be informed by your personal history of participation in education and the environment in which you are living and working.

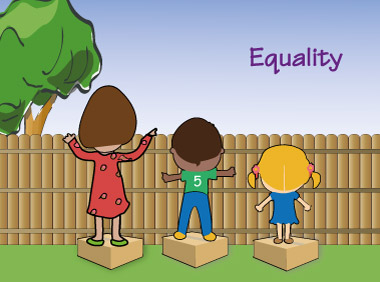

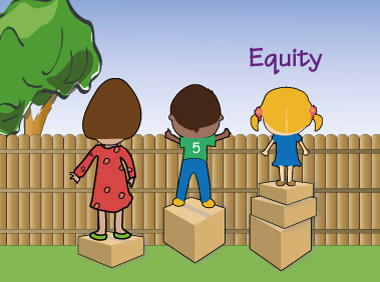

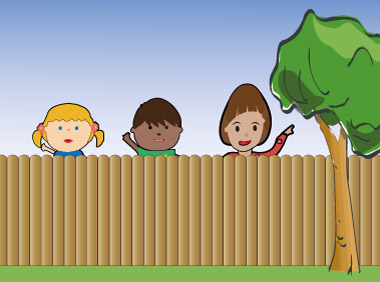

This is a series of three cartoons. In the first, three children of varying heights are trying to look over a fence. Each stands on a box but only the tallest child is able to see over the fence. The cartoon is labelled ‘Equality’.

In the second, the tallest child is standing on one box, the middle-height child on two boxes and the smallest child is standing on three boxes. All can now see over the fence. The cartoon is labelled ‘Equity’.

The final cartoon shows the children from the other side of the fence. All are smiling and their heads appear at equal height above the fence.

Activity 1

- Jot down a few initial thoughts about what ‘equality’ in education means to you.

- If you can, talk to an elderly family member or friend, or someone who has been educated in a country or culture different from yours: ask this person how s/he thinks of ‘equality’ in education

- What do you see as the dimensions of equality which you consider important?

- Now think about an educational context with which you are familiar. This might be the institution in which you practise or an institution you attended, or one which a member of your family attends. What does achieving equity for learners need to look like in this context? What does it feel like for learners/students, teachers, you? Spend a few minutes jotting down your thoughts.

- Compare this description with the account given by the person to whom you spoke for task 2 above.

Discussion

You may have thought about equality in terms of the resources allocated to education for different groups within society: for example, in England, a school usually receives a resource allocation with regard to the number of pupils who are considered to have ‘special educational needs’. Other mechanisms for resource allocation will operate in other jurisdictions. You might have expressed it in terms of students having opportunities to participate in the whole range of education experiences regardless of their backgrounds: for example, you might ensure that all students have access to sporting facilities in their neighbourhood. You might have thought about learner outcomes: for example, do students with a range of socio-economic status seem to be ‘equal’ as regards their transition to university, subject or career choices? You may have found it difficult not to simply describe equality as holding everyone of equal worth. These are all legitimate understandings of the notion of equality and we suggest that by comparing ideas with others, you will encounter a rich array of understandings and experiences.

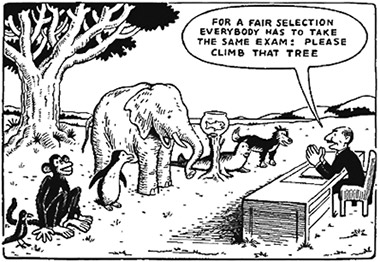

In this cartoon, the outside scene is dominated by a very large tree. A man is seated at a traditional teacher’s desk in front of a row of creatures: a bird, a monkey, a penguin, an elephant, a fish in a bowl, a seal and a dog. The man is saying: ‘For a fair selection everyone has to take the same exam. Please climb that tree.’

2 Other perceptions of equality

The concept of equality and how we should address inequality has been debated over many centuries by philosophers, theorists, politicians and campaigners; its meaning remains highly contested and open to interpretation and negotiation.

Along with a moral imperative to enable everyone to participate in learning, in many countries there is a legal imperative to avoid discrimination against different groups of people. In the UK, for example, the Equality Act 2010 requires education providers to avoid discrimination and make reasonable adjustment for disabled students. Within legal frameworks aiming to protect individuals and groups from discrimination, recent approaches to equality in education tend to fall into two groups – those emphasising equality of opportunity and those focused on equality of outcome. As the illustrations in this course highlight, addressing equality is often far more complex than it might first appear to be. One of the things you are encouraged to do is to challenge ‘simple’ explanations and ‘disrupt’ commonplace assumptions. You may find that this shifts and develops your understanding of ‘equality’ and the aspects associated with it.

The various approaches to ‘equality’ are based on different notions of what is valued and whether individual agency or society structures are seen as the primary force in determining life chances. The approaches fall into two main groups: those that focus on equality of opportunity (i.e. setting everyone off at the same starting point – or ensuring a ‘level playing field’) and those that focus on equality of outcome (i.e. aiming for equal success among different groups in society). Can you think of an example of each of these?

Each of these two main approaches has what is termed a ‘strong’ (or doing the maximum) and a ‘weak’ (or doing a minimum) version. They are usually associated with different political stances.

2.1 Equality of opportunity

Those who take the quality of opportunity approach focus on removing barriers. Thus, to give some examples from education of a weak version of this approach, a grant might be made for families in poverty so that they could afford the uniform for their child to go to a grammar school; or special coaching might be given to ensure that sixth formers from a socially economically disadvantaged area could achieve top grades in 18+ examinations and be in a position to apply for a top university. The problem with this is that it assumes that ‘the problem’ is one merely of functional access and it ignores less visible barriers. Critical theorists such as Pierre Bourdieu argue that individuals are shaped by the structural features of the social context into which they are born and within which they grow up.

In Bourdieu’s terms, we all have different profiles of ‘capital’ and we need particular capital in order to thrive in particular contexts or cultures. Thus, if ‘going to grammar school’ is something alien to the context in which someone has lived, the mere fact of being given the money to buy uniform will be insufficient to encourage the young person to take up the grammar school place. Similarly, if ‘going to Oxbridge’ is not an assumed route in the context in which someone has grown up, s/he will not think about doing it even if s/he has the necessary qualifications. The social structures need changing if behaviours are to change. Aspirations need a process if they are to be realised. A strong version of this approach would look towards ‘positive discrimination’ or compensatory action. Examples from education are the Sure Start programme for early years education in the UK – or Head Start in the US. You will note that these are targeted – rather than universal (e.g. ten hours free child care for all families) initiatives so they can be regarded as operating with a deficit view of some individuals (i.e. ‘you need help’) rather than making radical changes to society and the way things are.

2.2 Equality of outcome

The second approach to equality, with a focus on outcomes and what happens as a result of initiatives to enhance equality, calls for radical change. So if we take our example of university entrance, the radical approach would be to require certain proportions of student background characteristics within a particular cohort of students (e.g. to prevent top universities being entirely dominated by pupils from fee-paying schools) and allow for differential scale of entry qualifications according to this background (i.e. expecting higher grades from those from fee-paying schools). The focus shifts from the individual being conceived as ‘deficient’ to society being perceived as inhibiting to some people. Mere ‘opportunity’ is married with ‘process’ and ‘outcome’.

Within this approach there is a tension, however, between valuing the choices made by individuals and valuing the equality of outcomes – between ‘recognition’ and ‘redistribution’. Should people be allowed to make ‘bad’ choices which may limit what they are able to achieve in life? Thus, for example, should individuals be allowed to reject taking the sort of subjects for 16+ examinations that will allow them to progress to medical school at 18? The critical theorists would argue that social structures may be so powerful as to encourage what some might regard as ‘poor choices’ (i.e. choices which limit long-term achievement). The recognition of individual choice – so that individuals are held responsible for their destiny – can be favoured by governments which do not wish to engage in radical social change (which might give them a less favourable balance of power and disrupt the status quo) but which wish to appear to be promoting equality. Think about the government in the country where you live and work? How would you assess its approach to ‘equality’?

2.3 Analysing perceptions of equality

Now take a look at the following activity, where you will look at perceptions of equality.

Activity 2

Part A

- Look back at your own ideas in Activity 1. Which approach did your ideas most closely match or did you combine elements of both?

Discussion

The notion of equality of opportunity is prevalent in many policy statements, but has been critiqued for reproducing inequalities in educational outcomes. For example, in this approach, if boys are encouraged to take textiles courses, then their educational performance, even if low, is viewed as of little consequence and little attention is paid to their prior experiences and the understandings which they bring to the study of the subject. However, to ensure that ‘disadvantaged’ students have a fair opportunity of reaching a level of educational achievement which enriches their lives (and enables them to contribute to society) – equality of outcome – then it is argued that it is justifiable to have inequalities in ‘distribution’ (Rawls, 1997). For example, recognition of these students’ prior experiences and interests might lead to a change in approach to the teaching of the subject or the provision of additional materials or teaching.

Part B

- Try to find a public expression of an equality policy or statement for an institution where you practise or with which you are familiar. If you have difficulty finding one, you might like to look at the Open University’s policy. To what extent do you agree with the interpretation of equality expressed in the policy/statement you found?

Discussion

Despite almost universal commitment to equality in education, huge differences in the opportunities for, and benefits from, learning remain across the globe. As Wilson and Pickett (2010) comment, with reference to the UK, Western Europe and North America:

Children do better if their parents have higher incomes and more education themselves, and they do better if they come from homes where they have a place to study, where there are reference books and newspapers, and where education is valued.

3 An example of the construction of inequality

You will now read part of a report by Professor Danny Dorling, who is Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford. You will find other examples of his work and views if you put his name into a search engine.

Activity 3

- Read Chapter 2 (pp. 61–9) of Education inequality across EU regions.

- As you read, consider:

- the factors that influence educational disparities across regions and nations

- mechanisms which might be used to offset the impact of neighbourhood on educational opportunities. Which of these do you find most convincing?

Discussion

Educational experience can reflect and compound the effects of wider socio-economic disadvantage, but the extent to which this occurs in a particular locality and for different groups will be influenced by the mediating role played by the state and other bodies responsible for education provision, not only through legal, financial and organisational policies, but also by local history and social relations within that locality.

A key point in Dorling’s article is the way in which neighbourhood identity and its meaning are socially constructed, shaping and being shaped by residents’ aspirations and values around education. Identities are thus dynamic rather than static (p. 63).

4 A human rights approach

Much global discourse on equality in education focuses on a human rights approach, drawing on the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), although a number of scholars have argued that it is the existence of the UDHR, and subsequent documents drawing on it, rather than the moral arguments about rights, which frequently provides the rationale for the importance placed on education (Unterhalter, 2007).

In this human rights approach to education the emphasis is on the state’s role in guaranteeing education rights for all its citizens. These can be seen as rights to education, rights in education and rights through education (Subrahmanian, 2002) and embrace both negative rights, such as protection from violence, and positive rights, such as the use of the learner’s home language in school (Tikly and Barrett, 2011). This approach places the individual learner at the centre of the education process with a focus on meeting the needs of the learner. So a human rights perspective on education supports learner-centred practices and democratic school structures (Tikly and Barrett, 2011). Whilst the notion of ‘learner-centred’ pedagogy remains open to multiple interpretations (Schweisfurth, 2013) there are commonly accepted key features, such as valuing the prior knowledge and experiences of the learner, and seeing learning as ‘active’, involving learners in solving problems and constructing meaning.

The human rights approach has successfully raised issues of equality of access and focused attention on addressing structural inequalities for under-represented groups. But this focus on access rather than educational success can legitimise inequalities of output as people are seen to participate according to their own self-determined effort. The approach treats learning situations – whether school classrooms, nurseries, MOOCs or workplace learning situations – as isolated from the wider society in which they are situated. It is argued that the approach fails to take account of the lived reality of learners beyond the confines of the specific space within which they are learning. There is no basis for analysis of the social, cultural, historical and political influences from the wider context which impact on both learners’ participation and teachers’ practices (Tikly and Barrett, 2011). Thus learner failure and inequality are seen as primarily a result of specific practices within the institution or classroom.

5 Inequality in different contexts

In the following activity, you will read three contrasting articles, all of which illuminate aspects of inequality in education and explore policy, practice and pedagogical considerations in different contexts – rural India, Australia and New Zealand.

Activity 4

Part A

Read Kelly, O. and Bhabha, J. (2014) ‘Beyond the education silo? Tackling adolescent secondary education in rural India’, British Journal of Sociology of Education, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 731–52.

In this article the authors research the school attendance of adolescent boys and girls in villages in Gujarat, exploring the reasons for observed differences in participation in secondary education. It is not important for you to be familiar with the details of Indian education policy, but as you read this article you should make notes on the factors which are identified as restricting girls from benefiting from widened access to secondary education in this context.

You will notice that the authors draw upon the work of R. W. Connell, particularly on one influential book which stresses the socially constructed rather than biologically innate views of gender – for example, in relation to class and socio-economic structures in society. We will explore the ways in which taken-for-granted categories are socially constructed (for example, teachers’ assumptions about different types of learners) later in the course. After you have read the article, see what you can find out about Connell’s 1987 book (see the reference list) and the stance it takes in relation to investigating equality and gender.

Think about how you can find out more about Connell and her work via the internet, book reviews etc.

Think, too, about what you think are important aspects of power and sexual politics which have been taken up from Connell into the Kelly and Bhabha article.

Part B

Read Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T. and Teddy, L. (2009) ‘Te Kotahitanga: addressing educational disparities facing Maori students in New Zealand’, Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 25, pp. 734–42.

This case study from New Zealand describes an initiative designed to improve the educational outcomes of Maori students in secondary schooling. Again, it is not necessary to be familiar with the detail of the project. As you read the article you should note down what is identified as constraining participation in learning for Maori students and consider:

- whether there are other factors involved

- what lessons might be taken from this project for other settings, including perhaps your own practice

- what challenges there might be in adopting this approach more widely.

You will notice how the authors of this paper draw on the ideas of Freire in their arguments; Paulo Freire was an influential educator whose ideas on critical pedagogy are explored in detail in Section 2.

Part C

Read Fleer, M. (2003) ‘Early childhood education as an evolving “community of practice” or as lived “social reproduction”: Researching the “taken-for-granted”’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 64–79.

In this article, children’s access to early years provision is assumed to be unproblematic and the focus here is on the educational practices within such settings in Australia and similar highly resourced environments. The author problematises prevalent pedagogic approaches and the culturally specific origins of these practices. Note down what you perceive to be the notions of equality and/or equity embedded within the practices described by Fleer. What might be the implications of her analysis for your own practice or for a learning environment with which you are familiar?

Part D

You should now revisit the views of equality that you noted in Activity 1. Is there anything you would like to add to these views?

Note down any questions that you would like answered.

Compose a short message (max. 100 words) to summarise one thought from your reading this week and one question that you would like to explore more.

Discussion

Kelly and Bhabha (2014) argue that issues of equality in education cannot be seen in isolation from wider society and that merely ‘opening’ up education provision to offer formal equality of access may actually increase inequalities in participation between different groups of learners. The authors question whether the current strategy of the Indian government will be able to deliver equal educational opportunities for girls. They argue that, without recognition that boys and girls start from different positions and are constrained in different ways in their participation in education, there is a danger that the initiative may result in further marginalisation for some pupils based on their gender, class and caste. Thus this research points to the need to consider notions of equity as well as recognising equality, as indicated in Figures 1 and 2 of this course. However, addressing inequality through recognising the need for equity is usually a much more complex undertaking than just considering addressing equality.

At this point, take another look at Figures 1 and 2 and reflect on why it is more complex to consider equity rather than just equality in addressing issues such as access to education, disability, injustice and gender.

The issues explored in the article by Kelly and Bhabha are far from unique to rural India. Globally, one in four adolescent girls is not in school: many drop out during the transition from primary to secondary school, some drop out in primary school and a number have never been to school at all. Although education is potentially offering these girls new opportunities, the persistence of poverty and factors such as parental illness and environmental issues – drought and flooding, for example – can force families into balancing the need for survival in the present with any potential future gains that may come from supporting their daughters through school. The realities of daily life can overwhelm their own commitment to their daughters’ education and national provision and legislation.

These factors are exacerbated by being poor, living in a rural area and coming from an ethnic group that is discriminated against or excluded:

In Nigeria, for example, girls from a poor rural household will, on average, get fewer than three years of education, while in urban areas, girls in the same wealth bracket will get more than six years. If the girl is also from an ethnic minority, she will receive less than one year of education.

This intersection of gender, poverty, rurality and ethnicity acting to increase disadvantage and inequality is seen in many contexts. For example, a UNESCO report highlighted the fact that, at the time of the study, in Kosovo only 56 per cent of Roma women aged 15 to 24 were literate compared to 98 per cent of the rest of the population and only 25 per cent of Roma adolescents attended secondary school (UNESCO, 2008).

Interestingly, in this article Kelly and Bhabha do not explore the identities or views of the teachers at the secondary schools in the study; there is some evidence that increasing the number of female teachers in secondary schools serves to reassure parents and support girls’ school attendance (UNESCO, 2006) and the approaches taken by teachers within schools can enhance or constrain learners’ participation.

In the case study from New Zealand (Bishop et al., 2009) the focus is on teachers, their attitudes and behaviours within the classroom. The Te Kotahitanga project is not uncontroversial: teachers and teacher unions in New Zealand have challenged the way in which the project switches the location of the ‘deficit’ from within the Maori child to within the teacher and his/her practice. These critiques argue that this can make it difficult for teachers in the project to dialogue, work collaboratively and acknowledge the complexities surrounding Maori student/teacher/societal relationships.

The inclusion of this article, therefore, in no way indicates endorsement of this particular project; rather, it is intended to raise pertinent questions about the ways in which schools can act to constrain or limit participation in productive learning by some groups of pupils. Although the Te Kotahitanga project has been critiqued for focusing on one minority ethnic group in New Zealand, its initial activities highlight the important role accorded to teachers by parents and students in influencing student educational success. Further critique of the project centres on the way in which responsibility for Maori student success or failure has been placed on the teacher without consideration of the broader structures within which teachers practise, including the demands of formal assessments and the prevailing regimes of accountability in the profession. However, by placing a shift in the relationship between teachers and learners (ontological change) at the centre of the initiative it is aligned with a dominant global discourse of ‘learner-centred’ education (Schweisfurth, 2013). The legitimisation in teachers’ practice of individual students’ ways of knowing and being and recognition that these experiences mediate learning, act to reduce their positional identity as unsuccessful students and their subsequent marginalisation within the learning environment.

Marilyn Freer’s article challenges us to examine the beliefs and perceptions of childhood that we bring to practice in early years settings, arguing that what is understood as ‘good’ or ‘best’ education practice is based on a particular set of cultural practices and thus has the potential to position some children differently and inequitably. Freer invites practitioners and policy-makers to work towards more inclusive early childhood provision, paying attention to other world-views of constructs of childhood and childcare practices. In this course we are wary of identifying ‘good’ or ‘best’ practice; rather, we show how situations can be problematised so that practitioners can scrutinise the practice pertaining to their setting at a particular time.

In the next activity, you will look at an OECD report and consider how education is presented within it.

Activity 5

Read the OECD report ‘Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools’ (2012).

You do not need to pay great attention to the tables in the report (although you might like to consider what exactly they tell you), but as you read, make notes on:

- the way education is conceived

- the purposes that it is seen to serve

- the way in which inclusion is presented

- the sort of data presented to support the arguments

- the distinctions made between ‘input’ and ‘outcome’

- how success is ‘framed’

- the location of ‘deficit’

- the relationship with economic efficiency and political interest

- the way in which civil society – and criminality along with it – is presented

- assumptions about background characteristics

- considerations of the distribution of resources.

How would you summarise the OECD perspective on ‘education’ as presented in this report? What seems to be prioritised and what is not mentioned?

Conclusion

The readings you have encountered in this free course, Exploring equality and equity in education, all raise the key global and local issues associated with inequality and highlight the importance of considering not only the need for ‘inclusion’, but also of reflecting on and clarifying what we mean by related concepts such as equality, equity, democracy, participation, diversity and ‘education for all’, because how we develop our understanding of these concepts will drive how we go on to think about transforming our own practice to develop inclusive practice and address issues relating to inequality.

This course has also explored the ways in which the traditional views of ‘inclusion’ raise issues regarding how it may often prioritise the need to address equality, rather than provide deeper insights into how we can address equity given the complex and dynamic nature of the relationships and interactions between learners and educators within the constraints of their particular contexts.

If you enjoyed this free course, you might be interested in extending your learning by signing up for the Open University course EE814, of which this course is an extract. In this course, we extend the notion of ‘inclusion’ to a broader concept of ‘inclusive practice’. We argue that this is necessary because of the complexity and problematic nature of addressing educational inequality for learners within educational settings and workplaces which are in turn linked to the wider complex social relations of the local and the global world in which we live.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Felicity Fletcher-Camp.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course image

Adapted courtesy © Mary Quandt and Neil Mitchell.

Text

Activity 4; Part A: Kelly, O. and Bhabha, J. (2014) ‘Tackling adolescent secondary education in rural India’, British Journal of Sociology of Education, vol. 35 no. 4, pp. 731–752.

Illustrations

Figure 1: adapted courtesy © Mary Quandt.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University