7 Symbolism

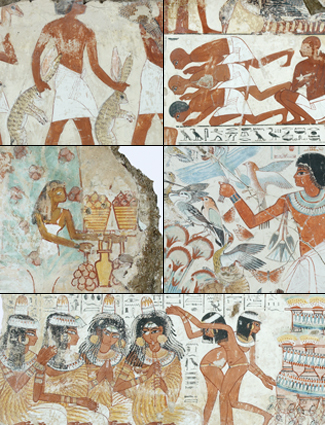

Just as the paintings in the tomb were not simple depictions of flowers, food, animals, recreation and work activities, but also carriers of a supererogatory symbolic range of meaning concerning progress into the afterlife, so too the tomb itself was not merely a physical space into which the mummies were placed. Like a Christian church in the shape of a cross, it too had a symbolic dimension. The organisation of the space, no less than its painted decoration, represented the transition from life to death, or more accurately, from life into the afterlife.

Watch this video in which Richard Parkinson and Paul Wood talk about the purpose of tomb-chapels.

Transcript

Melinda Hartwig, who has made a recent detailed study of Eighteenth Dynasty tomb-chapels, makes clear their great importance in ensuring the transition of the ‘justified’ individual into the afterlife. Their functioning had two distinct aspects, albeit connected: on the one hand to project the deceased through to the afterlife, on the other to commemorate his existence to those still living – the more to ensure that they keep up the various forms of commemoration that alone can ensure successful entry into the afterlife. ‘Remembrance was vital for the time after death, because the dead who were venerated and commemorated were retained in the community of ordered being. Those who were not commemorated were cast off into the land of non-being and relegated to an existence as ghosts.’

In short, the whole success of his ‘afterlife project’, so to speak, for any one individual depended on the efficacy of his tomb-chapel: both the beauty of the paintings and the power of their accompanying texts to generate the necessary admiration, prayers and recitations of his name, and the stranger, magical sense in which the images could assume the reality of the things they depicted in order to assure the spirit’s survival in the underworld. There was a tradition of visiting old tombs to admire their paintings, so that the quality and beauty of the paintings – that is, their purely aesthetic aspect – was integral to their memorial aspect.

The tomb-chapel is in effect an absolutely critical life-support system (or more aptly, afterlife-support system) for the akh, the transfigured being, on its journey to eternal life (Figure 24). There could hardly be a more compelling reason for getting the decoration right.