3 Contrasting purposes

Neither this difficulty of interpretation, nor the difference from the type of pictures with which we are familiar in our own culture, nor again the massive, powerful effect of the sculpture, mean that Egyptian art is unpopular. Quite the reverse is true; it is widely admired, and frequently evoked in many modern designs. Figures 4 and 5 are photographs of an office building in London that was built in the 1930s.

Very few people would ever associate Egyptian art with those conditions that Baudelaire picked out as defining his world and its art: the ‘ephemeral, the fleeting and the contingent’.

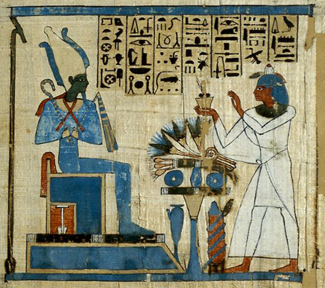

Indeed it is quite true that while Impressionist paintings seek to give a vivid representation of contemporary reality, Egyptian paintings are doing something very different (Figure 6). Most surviving examples are from the walls of tomb-chapels. Some do contain striking details of daily life, fashionable clothes and jewellery, scenes of leisure, scenes of work. But the balance is different. A nineteenth-century painting of modern life sets out to tell us the truth of that form of life. For Baudelaire and those artists who answered his call, the truth of modernity was intended to replace the worn-out myths of classicism and religion. If what Baudelaire called ‘the eternal and immutable’ came into it at all, it had to come through the modern.

In Egyptian paintings in tomb-chapels it is almost exactly the other way round. Representing the experience of daily life, particularly the good things of that life as it was lived by the wealthy, was a way of helping ensure their continuation in the afterlife. The paintings’ apparent concern with the here and now is not to be taken at face value.

Key point

Despite the sometimes naturalistic detail, what drives this art is an underlying concern with eternity, with humanity’s relationship to the gods, with life on Earth not regarded on its own terms as we would understand it, nor indeed as simply followed by the afterlife, but informed by it at every turn.

The sense of this is conveyed by a harpist’s song from a generation or so after Nebamun.

No one can linger in the land of Egypt ... The time of deeds on earth is only the occurrence of a dream.