8 Selection based on subject

Undoubtedly, one main concern for d’Athanasi in selecting fragments would be basic and physical, i.e. the size of pieces that he could transport, as well as what would literally hold together. The fragments were fragile, their paint surfaces even more so, and transport conditions were primitive. This in itself would have constrained what he was able to remove.

There is, however, something more consistent about what was omitted. Mostly it seems to have been elements that would have diminished the naturalism of the scenes. Salt and d’Athanasi would have had considerable knowledge of ancient tomb-chapel art. To them, the large, static figures would have been the most formal, conventional and common; that is, they would have been the least interesting and appealing, despite the significance they would have originally had in producing the meaning of the compositions. To take the most obvious example, the servants, hares and gazelle, so attractive to d’Athanasi, would have been meaningless in the original scheme without the figure of Nebamun to accept them as a form of tribute.

By the early nineteenth century, the western, post-Renaissance, Academic tradition of art had been in place for over three hundred years. In a very powerful sense, it was what ‘Art’ was. Things that fell outside it were not really regarded as art at all (and certainly, things that we regard as art would not have been either). The cornerstone of that tradition was lifelikeness, especially in painting: the production of credible illusions of objects and actions in three dimensional space on a two dimensional surface; believable, that is, from the viewpoint of the picture’s spectator.

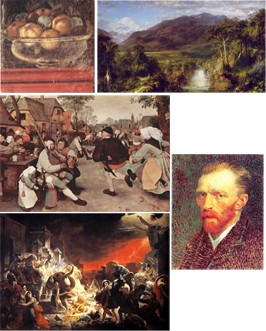

That was not the end of the matter however. For the Academic system was itself internally articulated. Alongside the various technical requirements needed to produce credible and engaging illusions – such as modelling, composition and so forth – the subject matter that was to be depicted was itself arranged into various categories (Figure 29).

These categories were known as the hierarchy of genres. In ascending order of importance they were:

- Still-life

- Landscape

- Genre (here meaning scenes of ordinary life)

- Portrait

- History (meaning complex multi-figure compositions combining attitudes of stasis,

- Movement, clothed figures, nude figures etc, usually of Biblical or Classical subjects)

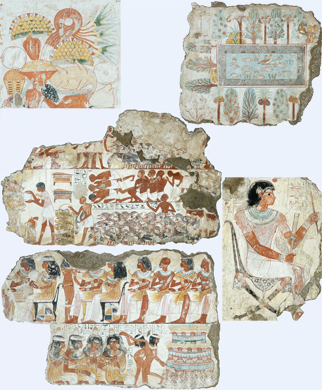

One of the most arresting features of the surviving fragments of the Nebamun tomb paintings is the extent to which they conform to these categories (Figure 30).

- The offering table functions as a still-life.

- The garden of the west is a sort of landscape.

- We have two ‘portraits’ of Nebamun, overseeing the produce and hunting in the marshes, one at work and one with his family.

- The scenes of the farmers with their cattle and geese, the offering bearers with the hares and gazelle, and the images of harvest are all genre scenes.

- The banquet functions as a particular type of multi-figure composition combining clothed and nude figures in a way that would have been appealing to nineteenth-century gentleman connoisseurs.

This is not, of course, to say that d’Athanasi went looking for a landscape or a portrait, let alone set out to recreate the whole hierarchy of genres. What it perhaps does say is that the ‘period eye’ of the early nineteenth century unconsciously thought of ‘art’ in more or less those terms. What was interesting to look at, what was arresting ‘as art’, was interesting or arresting according to such categories and criteria.

Fortunately we do have a fairly well-developed idea of what an early nineteenth century European would have found interesting or arresting in the field of visual imagery. It is also worth bearing in mind that ‘interesting visual imagery’ would have been inseparable from two dimensions whose very pervasiveness make them easy to overlook: time and space. Or more particularly, history and geography, in respect of both the interestingly, even challengingly exotic, and the reassuringly familiar.

The next three sections explore the ‘discourses’ of early nineteenth century art that are particularly relevant here.