2.4 Other differences

Greco-Roman literature, art and archaeological remains give us an indication that people lived with many other types of bodily differences. For example, there exist depictions of people with achondroplasia, commonly known as dwarfism. These are found on Greek and Roman vase paintings. There have also been a few skeletal remains of people with the condition found buried in Roman necropoleis.

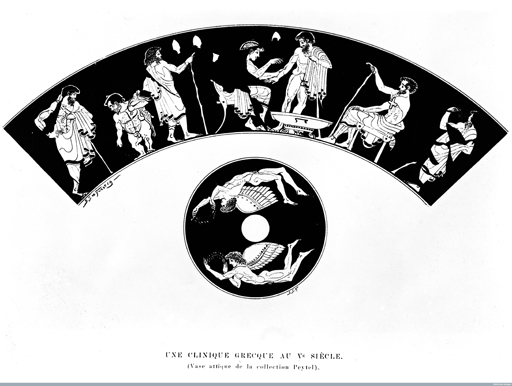

Figure 12 is from a fifth century BCE pot (an aryballos), which you saw in Week 1, Knowing what’s normal [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . It shows people using walking aids and a person with achondroplasia. It seems to present a doctor’s surgery, with the doctor letting blood from the arm of one patient. The other people there include a man leaning on a staff and a dwarf. Is the dwarf a patient, or is he a servant or slave of the doctor?

In the Hellenistic period – after Alexander the Great – there was a tendency towards more realism in sculpture. From this period, and from the Roman era, there are small statuettes which show people with gibbosity, or a hunched back. This was a problem known to affect people in their old age, and sometimes paintings on Greek pots depict older men with hunched backs using a walking stick to aid them. In the first century BCE bronze statuette shown in Figure 13, the outstretched right hand may have held a stick.

Depictions in art also show people with obese and emaciated bodies. Obesity was a sign of excessiveness, as discussed in Week 3, and therefore a lack of balance. Emaciation was sometimes associated with envy. However, it was likely suffered by anyone who was unable to get food, which is an indication of a social problem rather than a moral one.

Hermaphroditism, a congenital condition where a person is born with both male and female genitalia, was known about in the ancient world. The term comes from the name of the god Hermaphroditos, who was the child of two Greek deities: Hermes, the messenger god, who was also known for his tricks; and Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Hermaphroditos (Figure 14) had both sets of genitalia. He was often depicted in art with a feminine body, but with male genitalia.

Other known bodily differences have to do with sensory perception. Blindness was a problem, as you have seen in Week 2. Deafness was also a problem people had to face in the ancient world, though as far as we are aware, there existed no means to help people with weak hearing. There is little written on the subject in ancient texts, but what does exist indicates that people with deafness were usually unable to speak. The Greeks may have thought people with this combination of problems – deafness and muteness – lacked the capacity for reasoning. Speech, like the ability to use one’s hands, was seen as an important distinction between humans and the rest of the animal world.

In contrast to being mute, stuttering was also a problem known to have affected some people. The Emperor Claudius, as previously mentioned, had a stutter. The Greek historian Plutarch said that Demosthenes, an Athenian politician and orator (c. 384–322 BCE), was afflicted with speech problems as a child. He is not specific, except to say that the condition led to a weak and unpleasant voice. In societies as focused on the skill of public speaking as ancient Athens and Rome, it’s impressive that anyone with a speech defect could nevertheless work as an orator.

A speech made in fourth century BCE Athens, Lysias’ On the refusal of a pension to the invalid, provides evidence that some people who were adunatoi – a word which means literally ‘without power’ and which has been translated as ‘disabled’ – received some money from the state. Another source, Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians, says this pension was given to the poor and those ‘incapacitated by a bodily infirmity’ (Constitution of the Athenians, 49.4). Lysias contrasts those who are hygiainos (in good health) and those who are adunatos (disabled) (Lysias, 24.13), and the latter should be regarded as deserving of pity.