4.1 Brain structure and function

Research into the structure and function of the brain draws extensively on a range of

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) monitors brain activity while a person is performing psychological tests, such as recognising faces, responding to emotional stimuli or understanding language.

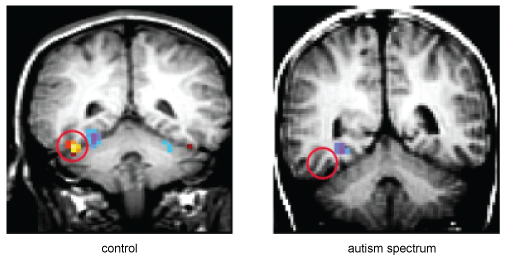

The patterns of brain activity revealed by fMRI may differ in people with autism, compared to the neurotypical population. For instance, there may be reduced activity in a brain region called the

Atypical patterns of brain activity are also observed when autistic people perform tasks such as the ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ test illustrated earlier.

(See Lai, Lombardo and Baron-Cohen, 2013, for an overview of findings like those discussed in this section.)