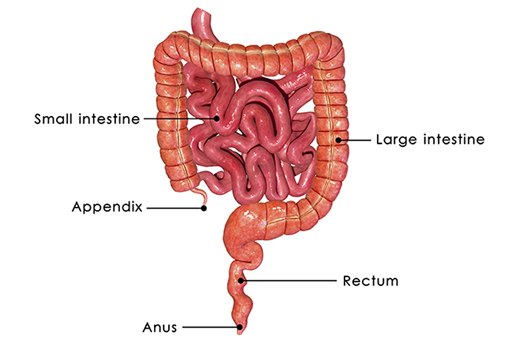

3.5 The large intestine

Once most of the ‘goodness’ has been absorbed from the food through the walls of the small intestine, the fibre part of the diet and lots of water are left in the large intestine (Figure 11). If you have ever had diarrhoea, you know what the large intestine contents are like before they are properly processed. The inside surface of the large intestine is much flatter than that of the small intestine. This is because water is much easier to absorb into the blood than nutrients.

Also making their home in the large intestine are enormous numbers of microbes. Although people can survive without any bacteria in their large intestine, these microbes perform several really useful functions. For example, they can help to break down some food molecules that were not susceptible to breakdown by the digestive enzymes, particularly some carbohydrates, including cellulose. People who eat a high-fibre diet often have more of these sorts of bacteria.

Microbes in our large intestine are also the source of some vitamins – such as biotin and vitamin K. They play an important role in keeping any dangerous microbes under control that might get into our gut in food and manage to escape being destroyed by the stomach acid. Taking antibiotics for an unrelated infection can destroy these ‘good’ microbes and cause diarrhoea, particularly in hospital patients and elderly people.

Once the water has been absorbed in the large intestine, fibre and a lot of dead bacteria are left, to be disposed of by the body. Peristaltic movements compress these into faeces, which are about one-third bacteria and two-thirds fibre and other undigested food. They are stored in the last part of the large intestine – the rectum – before being expelled from the body through the anus.