4.1 Satellites – the next big advance in citizen science?

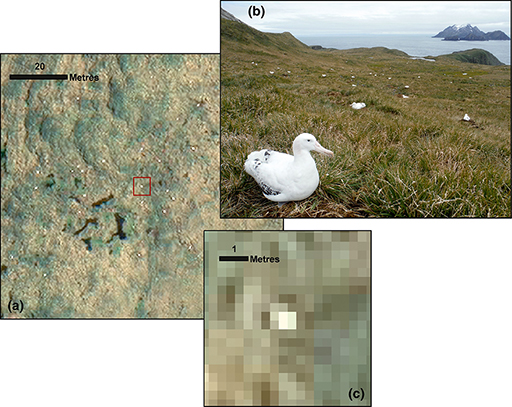

The definition available in satellite images has recently increased to the point where large animals such as albatrosses are visible as individuals. The northern royal albatross shown in Figure 7, for example, is one of the world’s largest birds, with a wingspan of 3.2 m, and its size makes it just visible on satellite images. Each of the white dots in the WorldView-3 images of an albatross colony in Figure 8 appears to be a single bird.

Activity 4 Satellite pros and cons

Now that you are nearly at the end of this course, take the albatross example as a guide and then consider the problems that might arise when setting up a citizen science project to estimate the population size in a hypothetical species of light-coloured animal using satellite imaging. Think about how you might maximise the accuracy of the data gathered and about whether there is any way to check that the data derived from photographs is a true reflection of the real population.

Answer

In the images in Figure 8, each bird is shown as a small, light dot. Asking more than one person to count the number of dots on the photograph by eye and taking the mean value increases the confidence in the data. However, as each animal is just a dot, it is possible to include in the count other species that are light coloured, or even light-coloured patches of rock. Also, it would be impossible to separate breeding and non-breeding individuals via this method.

If the actual site surveyed was accessible, it would be possible to compare a ground survey with a satellite survey of the same area on the same day. However, as you would swiftly appreciate, that is a daunting task, and of course it might be a cloudy day!

Refer to Fretwell et al. (2017) to find out more information about how the albatross survey was carried out.

You will realise from the albatross study that aerial imaging has great potential and that the technique is likely to be applied to other populations. The photographs produced by this study were assessed manually, but in future it seems reasonable to expect that fully automated counting will be possible, although doubtless at some cost. Where large amounts of data are being collected, however, there is a role for volunteer citizen scientists, and the role they play – the role you could play – will develop alongside the application of technology.