Introducing environmental decision making

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 24 April 2024, 7:35 PM

Introducing environmental decision making

Introduction

We all make decisions in everyday life, both as individuals and in groups. These range from simple – for example, choosing what to eat, which route to take to work, which products to buy in the shop – to complex decisions about changing jobs, moving house, choosing schools and participating as a member of a local community in planning decisions and improvements.

What processes do we go through in making these decisions about different possible courses of action? Are they the same every time? Are they the same for everyone?

Just as there are different types of decision, there are also different approaches to decision making that are relevant in different circumstances.

Some decisions are made rationally and logically, while others are made more instinctively or less consciously, sometimes based on the smooth performance of a practised skill. Yet others appear not to be made intentionally at all, but are dictated by sudden changes in knowledge or circumstances – for example, when trying to decide between one route and another and finding that one way is blocked. In practice, other options may still be available but it appears as though the decision has been made for you. Variation in choice may also mean that one person has a decision to make and another does not. (My examples, above, of choosing what to eat or buy assume that I have a choice.)

Individuals and groups also have different preferences for how they make decisions and articulate what they do. Decision making is, at times, such a dynamic process that it can be difficult to tell whether a decision is being made or not. Whether we are directly involved in decision making (and in what capacity) or how we are affected by decisions others appear to have made, also affects our perspectives on decision making.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 3 study in Environment & Development

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

recognise and explain some different approaches to decision making

recognise and explain some major factors that influence decision making

recognise and explain what is understood by environmental decision making and several key concepts that are relevant to it

recognise and explain how to identify some environmental issues that are of interest or concern and explain why

recognise and explain what the authors of the course mean by a system, its boundary and environment.

1 Introduction to decision making

1.1 Approaches to decision making

Think about some of the decision-making processes in which you have been involved. Do you recognise any of the following four approaches to decision making?

(i) Rational choice

There are many variations on this theme. The aim is to identify and choose the best option in a particular set of circumstances by systematically going through a series of steps such as:

- Consider the situation as a whole.

- Identify the decision(s) that need(s) to be made.

- Collect data on the range of alternatives.

- Develop criteria for assessment of the alternatives.

- Assess the alternatives against the criteria.

- Choose one alternative.

- Monitor the outcome of the decision.

In practice, you will rarely be making a decision in a static situation and may need several iterations of this type of process before you reach a decision. This is mainly because new alternatives or criteria emerge at a later stage. One example might be in deciding which computer to purchase to serve a group of people. Sudden availability of a cheaper or more powerful alternative, or changes in the composition of the group it has to serve, are examples of the sorts of change that can occur that will affect the outcome of the decision.

(ii) ‘Rational up-to-a-point’ decision making

In situations where there is more uncertainty and limited data available it might only be possible or desirable to approach certain stages of the decision-making process rationally. Say, for example, you are allocating some small grants for local community improvements. You assess the proposals systematically and still end up with six very worthy projects from which you can choose only one. Some people would claim that you could continue to apply rational choice by going through further iterations of developing criteria and collecting data, but there will probably be diminishing returns from the additional effort. Another approach would be to select one of the final six quite randomly. Any of them would satisfice (represent an adequate or ‘good enough’ decision), at least from the perspective of those disbursing the grants. The term satisfice describes a course of action that satisfies the minimum requirements to meet a goal rather than trying to achieve the maximum (biggest) or optimal (best) outcome. It was first coined by a key contributor to decision-making literature, Herbert A. Simon, in his Models of Man 1957.

(iii) Decision making in disorder – the ‘garbage-can’ decision process

James March has written several critiques of ideas on rationality in decision making. The following quote and the idea of ‘garbage-can decision making’ comes from his 1982 article ‘Theories of choice and making decisions’.

Theories of choice underestimate the confusion and complexity surrounding actual decision making. Many things are happening at once; technologies are changing and poorly understood; alliances, preferences and perceptions are changing; problems, solutions, opportunities, ideas, people and outcomes are mixed together in a way that makes interpretation uncertain and their connections unclear.

The garbage-can metaphor describes the messy, complex and disordered way in which, at a particular moment in time, all decision makers are simultaneously involved in a range of activities and not just in a single decision-making process. These concurrent activities are all thrown together in the minds of decision makers, like in the jumble of a garbage can. March suggests that in such messy situations particular ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ often become attached to each other because of their spatial and/or temporal proximity to each other, not because of rational choice.

This implies that understanding why decisions are made in one area frequently requires an understanding of what is going on elsewhere at the same time. The original work of March and his colleagues was done in the context of some university organisations. They described a situation where:

Recent studies of universities, a familiar form of organised hierarchy, suggest that organisations can be viewed for some purposes as collections of choices looking for problems, issues and feelings looking for decision situations in which they might be aired, solutions looking for issues to which they might be an answer, and decision makers looking for work.

It is not difficult to identify similar contexts today, with an environmental dimension, though not necessarily at the level of a single organisation, for instance when considering our use of technology in the context of climate change.

(iv) Personal beliefs approaches to decision making

There are many other personal theories and beliefs around decision making, based on an individual’s experiences of decisions. Here are just a few:

- ‘... toss a coin to make the decision, if you then want to make it the best of three you know which decision you want to make’

- ‘... always dismiss the first and choose the next option that is better’

- ‘... better to make any decision than no decision at all’

- ‘... you never need to actually make any decisions if you just keep on endlessly collecting views and feeding them back to people until the decision is made’

- ‘... you can tell whether it’s the “right” decision by how you feel about it’.

Activity 1 Consider your own decision-making experience

Consider your own experience of making decisions, or perhaps in actively refraining from making decisions. Note down examples where the (a) rational, (b) rational up-to-a-point, (c) garbage-can and (d) personal beliefs approaches to decision making seemed to apply (one for each).

Discussion

- (a) I used rational choice to help in deciding which applicant to appoint to the post of ‘field assistant’ on a project I was managing. Detailed criteria were developed for both person and post and all applicants were assessed against those criteria.

- (b) Rational up-to-a-point decision making helped me decide which plants to grow in my garden this summer. Several plant varieties met all my criteria. There was uncertainty about weather conditions and my time and inclination for weeding; clarifying these uncertainties would have helped me further with rational choice but I did not bother to follow these up, so in the end my final selection was partly arbitrary.

- (c) The decision for the complete removal of an old hedgerow on farmland opposite my house this spring as the birds were nesting seemed to me to be an example garbage-can decision making. The hedge certainly needed attention at some stage as part of it was dead. However, uprooting the whole hedge rather than removing the dead sections, possibly at another time of year when it might have had a less damaging effect on birds, was due to the availability of a contractor’s time and equipment, as a job elsewhere on the farm had been finished early. This factor was combined with the absence that afternoon of others both on and off the farm who would have made a different decision. (My ‘conservation of birds’ values are showing here. Someone more concerned with other aspects of the impact of the decision, such as the costs of equipment hire, would perhaps judge it differently!) The action of pulling up the hedge at that time resulted from the combined set of circumstances, not a ‘hedge-centred’ decision-making process!

- (d) I subscribe to the view that ‘You can tell whether it’s the “right” decision by how you feel about it’. I decided recently that I could not go to a conference I was invited to attend – lack of both time and money meant that I felt the only rational decision was to decline the offer. I then realised I was disappointed about the decision and that it did not seem the ‘right’ decision for me at that time, and that if I thought about it differently and considered it as an opportunity to progress several things I was working on, I could probably find away to go. I eventually reversed my decision. This could be thought of as a second iteration in rational decision making, in that what I had done was to assess the decision against new criteria that had emerged, but in practice I reversed the decision because of how I felt about it, not because of rationality!

In practice, most decision making involves a combination of approaches. So, why are people not completely rational in their decision making? James March in another paper, ‘Limited rationality’ (1994), claims that although decision makers try to be rational, in a particular context, they are constrained by limited cognitive capabilities and incomplete information, so although they often intend to be rational, their actions are often less than rational. Not being entirely rational is just part of being human! In this paper, March does not discuss the role of emotions in affecting rationality in decision making but he has written on this topic elsewhere (March 1978). There is a lot of literature on emotion and decision making related to understanding human cognition (the mental process of knowing and developing knowledge) and what motivates human behaviour, particularly in the areas of medical decision making and psychology (e.g. Schwarz (2000) and Ubel (2005)).

Activity 2 Information constraints

Read the extract below from March (1994) and complete the following activity. What are the four main information constraints that March believes face decision makers in organisations? In your experience, are these constraints also relevant in non-organisational settings?

Discussion

- (a) problems of attention;

- (b) problems of memory;

- (c) problems of comprehension;

- (d) problems of communication

Organisations impinge on so many aspects of our lives it is sometimes difficult to tell when we are outside an organisational setting! But if, for example, I consider a decision at home where there are many options, such as ‘How will I reduce my use of energy (electricity and gas)?’, I seem to run into all four of the information constraints March refers to, just because I make a wide range of choices in this area. I have many electrical appliances (fridge, cooker, television, etc.), and both electric and gas heating, so deciding what and how to change, to reduce my overall use of energy, is a fairly complex task.

1.2 Factors that influence decisions

Now that these different approaches to decision making have been considered it is possible to extract a number of linked factors that influence decisions:

- The decision makers

- The decision situation

- Thinking in terms of a problem or an opportunity

- Decision criteria

- Time

- People affected by the decision

- Decision support – theories, tools and techniques.

Let us briefly consider each of these factors in turn.

1 The decision makers

Different people approach decision making in different ways. Individuals are unique in terms of their personalities, abilities, beliefs and values. They also each have traditions of understanding out of which they think and act. Even when the same data is apparently available to all, people will interpret and assimilate the data in different ways and at different speeds. Some people are very confident about weighing up a situation and making decisions, others less so. Some like to take more risks than others. Competences, such as the ability to listen to other people, also vary. Social pressures affect everyone to varying degrees and the approval or disapproval of friends and colleagues may be more important to the decision maker than being ‘right’ every time. Political beliefs also vary and people will rank differently, for example, individual and social gains from a situation.

Each individual develops personal beliefs and values, including those relating to their environment, through different life experiences, and hence brings a different perspective to a decision situation. Some people will also have more at stake in a decision outcome than others. There are therefore many issues around who is involved in decision-making processes and how they participate.

2 The decision situation

The garbage-can approach to decision making showed that the decision situation is often messy and complex and that apparently unrelated events can affect decision outcomes, depending on what else is going on at the time the decision is taken. For any individual or group there will be both ‘knowns’ and ‘unknowns’ in a decision situation. In the examples so far, in the text and in the answer to Activity 1, the unknowns range from prices and models of computers to weather conditions and availability of people. It is not always easy to work out which aspects of a decision situation are relevant.

Elements of change, risk and uncertainty are common in decision situations and recognising and making sense of these elements are two of the main challenges that decision makers face. Risk implies that we know what the possible outcomes of a decision may be and that we know, or can work out, the probability of each outcome. Uncertainty, on the other hand, implies that there are unknowns and that we can at best guess at possible outcomes and their probabilities or consider a range of imagined scenarios. There are ways of reducing some of these unknowns by using relevant data, techniques (for example, ‘what if’ modelling) and the experience of participants. Many of the ideas and techniques outlined in this course are intended to help you recognise and evaluate different aspects of decision situations, to work out which are relevant and what you can do about them.

3 Thinking in terms of a problem or an opportunity

When you have started to consider an issue and are approaching a decision, do you think in terms of opportunities, problems or both?

A potential problem can often be turned around by thinking about it differently.

For example, Shields Environmental in the UK has developed a business that provides two specialist services – reuse/recycling of mobile phones and reuse/recycling of telecommunications network equipment. Fonebak was one scheme they have developed. It was the world’s first mobile phone recycling scheme to comply with all legislation. Over 18 million phones each year were being replaced in the UK around 2000 and without opportunities for reuse and recycling would have probably gone as potentially hazardous waste to landfill. In Fonebak’s first two years of operation (2002– 04) the company processed 3.5 million mobile phones for reuse and recycling, from 10,000 collection points across Europe. Many phones were reused to provide affordable communication in developing countries and those that could not be reused were recycled, with their materials put back into productive use. In taking up this opportunity Shields Environmental has not only developed a successful business but also enabled others to comply with environmental regulations.

Robert Chambers, in his book Challenging the Professions (1993), argues that there are two main disadvantages to thinking of a situation as a problem rather than as an opportunity. First, it has negative connotations, and second, it can lead to misallocation of resources if we think in terms of problem solving rather than seeking out new opportunities. Problems and opportunities seem to have other characteristics also, which are listed in Table 1. Do you agree with them? Can you think of any others?

| Problem | Opportunity |

| Negative connotation | Implies positive action |

| Often used with adjectives like ‘worrying’ or ‘difficult’ | Often used with adjectives like ‘exciting’ or ‘new’ |

| Needs solving? | Implies choice |

| Can confine both thinking and action | Can liberate enthusiasm for dealing with a situation |

| Recognises constraints | Recognises new directions |

| A situation of disadvantage | Turning situation to own advantage |

This is not to suggest that all problems can be turned into opportunities. One person’s problem may well be another’s opportunity, which will not always help the person with the problem. But it is worth remembering that how a decision-making situation is thought of can affect what actions are taken, and that there might well be opportunities in what appears to be a problem situation.

4 Decision criteria

The criteria that are established and used to evaluate alternative courses of action in decision making will certainly affect the outcome of a decision. Different criteria will be appropriate in different situations but are often needed both to help make a decision and to make apparent the basis on which it is made.

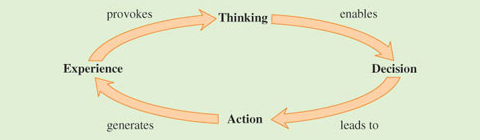

In group decision making, exploring and deciding on criteria is one way of developing a shared understanding of a situation. Different decision makers with different beliefs and values are likely to identify different criteria and give a different weighting to them (see Figure 1). For example, finding an option for a new housing site that will satisfy (a ‘good’ decision) or at least satisfice (an ‘adequate’ or ‘goodenough’ decision) all those involved will usually mean compromises or trade-offs.

Specific criteria can help to identify areas where there is agreement and disagreement. Criteria for the new housing site might include, for example, how existing land use is valued and by whom, services and housing provision available in the vicinity, likely disturbance or enhancement of the area and implications for road safety. There will be different views on what is acceptable for each of these aspects and often a need for negotiation. Criteria such as these are frequently worked out at different levels, as part of the regional as well as more local planning processes.

5 Time

A decision is made at a particular time in a particular set of circumstances. The decision situation can change very rapidly so what appeared to be a rational decision at one time might later appear to be anything but that.

One aspect of the time dimension that is particularly apparent in the ‘garbage-can’ decision-making approach is that the outcome of a decision may be affected by concurrent, but otherwise only marginally related, events. One example of this might be the unexpected availability of additional resources or a reduction in resources because of another project going on at the same time elsewhere. Another example might be the way that strong opposition to, or support for, a new development may unexpectedly surface because of events elsewhere.

Time is also a factor that can affect the nature of people’s participation in decision making. Skills are needed to be able to judge the urgency of decision-making processes, who needs to be involved in which stages of decision making within a particular time and resource frame and to what extent timing can be negotiated and with whom.

6 People affected by the decision

People who are likely to be affected by a decision can have considerable direct or indirect influence on the outcome of a decision. There are many ways in which this can happen. People affected might be ‘shareholders’ or ‘stakeholders’. Shareholders’ interests are economic; stakeholders’ interests in the decision are much broader than economic. Stakeholdings may be direct or indirect. Ways in which people affected can influence the decision range considerably. They may participate actively or proactively from the start, for example by being involved in the design of decision-making processes or in deciding on policy, or at other stages, e.g. through campaigning to try to overturn specific planning decisions, such as road building, industrial or housing development, or participate passively by withdrawing cooperation after the decision has been reached, such as refusing to use a facility that has been provided. There are issues of power to take into account in considering the nature of the influence that people affected by a decision can have.

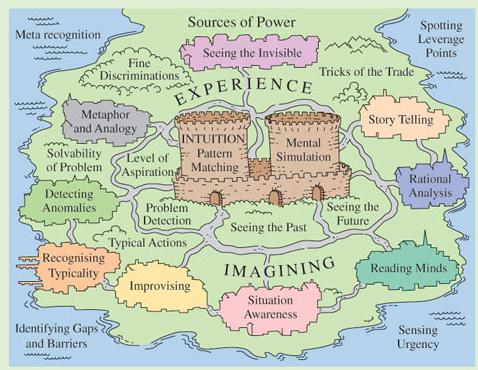

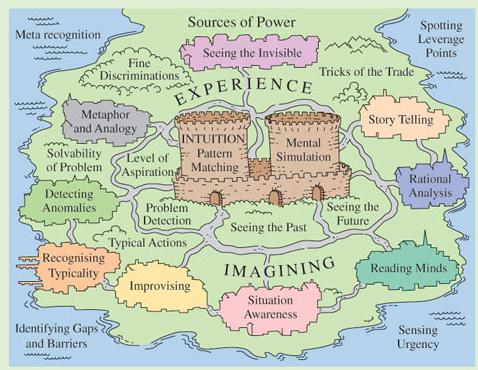

7 Decision support – theories, tools and techniques

Many theories, tools and techniques have been developed to support and explain decision making, for example in medical, legal and organisational contexts. They may offer support to decision-making processes, depending on how they are used. For instance, the ability to model aspects of a situation may address some of the information constraints mentioned in Reading 1. But note also that March (1991) commented that ‘any technology is an instrument of power that favours those who are competent at it at the expense of those who are not’.

Power relations, the role of different stakeholders and expertise in decision making and use of models for decision support must be taken into consideration. A great deal of literature also exists on areas such as decision theory and behavioural research on how decisions are made.

1.3 Decision making and policy making

Decision making is such an integral part of most people’s everyday lives that it is sometimes difficult to tell where decision making starts and ends.

An activity closely allied to decision making, yet different, is policy making. Policies are plans, courses of action or procedures that are intended to influence decisions. As such, they form part of the context for decision making, often providing guiding principles. But decision making is also a part of policy making and there is a dynamic relationship between decision making and policy making.

These two activities differ mainly in their purposes. A decision will usually be specific to a situation, even though it will be linked to other decisions in other situations. A policy however may apply more generically. Why does this difference matter? It matters when a decision made in one situation sets a precedent that may become a ‘de facto’ policy.

Examples where this has happened can be found in planning processes where precedents set are taken into account when appeals are made regarding granting planning permission. De facto policy also applies in some countries regarding prosecution of small scale polluters, where it is not practical to implement environmental legislation in a literal sense in all cases. Developing policy for dealing with diffuse pollution (i.e. from multiple sources) within water catchments is an example where decision making interacts with policy making. Problems of diffuse pollution are widespread, and where practical ways of improving diffuse pollution situations have been found, these have influenced policy options.

2 What do we mean by environmental decision making?

2.1 Concepts of environment

Activity 3 Your understanding of environment

The term ‘environment’ is used in many different ways and in many different contexts. Take a few minutes to write down two or three sentences that describe your own understanding of it.

The way in which our environment is perceived is central to the way in which we approach environmental decision making, so the concept of environment will be explored iteratively in this course. At this stage, I simply want to introduce the concept, to encourage you to be critical of how the term is used and to explain the way the term will be used.

The words ‘environment’ and ‘environmental’ appear a lot in everyday language. For instance I picked out reference to the environment, learning environments, the business environment, my home environment and environmental schemes in a couple of magazines I was reading recently. But in going on to read the articles in which those words appeared it became clear that those terms had little in common beyond a generic meaning of ‘contexts’ or ‘surroundings’ .

Activity 4 Substituting words

Read the following paragraphs. Write down some other words that you think could be substituted for the words ‘environment’ or ‘environmental’. Comment on how easy or difficult you found it to do this exercise and why.

(a) Concerns that the environment is being down-graded in EU policy-making have been fuelled by reports that major initiatives from the European Commission are to be delayed, and potentially watered down.

ENDS Report 366 (July 2005)

(b) The Court of Appeal has recently been required to consider the compatibility of the Environmental Assessment Directive with the UK system for dealing with outline planning applications.

Macrory (2005)

(c) Lack of Public Sector Transparency Distorts the Business Environment.

The Development Gateway Business Environment web page (2005)

(d) Hydro-electric power is pollution free and safe once it’ s up and running, although in creating it there can be tremendous disruption and upset to the environment, animals and nearby residents.

BBC Weather Renewable Energy – Water web page (2005)

(e) It brings together games players, makers, thinkers and artists in a unique environment where games fans and novices alike can experience a mix of old and new, fun and discussion in the context of cinema and media.

BBC website advertising the event ‘Screenplay 2004’

Discussion

- (a) protection of natural resources and management of wastes;

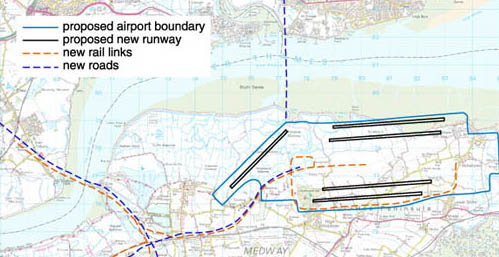

- (b) effects of new developments such as dams, motorways, airports or factories on their surroundings;

- (c) set-up or context

- (d) physical and biological elements;

- (e) context or ‘space’.

In each case the word environment or environmental seemed to be used in a broad sense so I didn’t find it easy to find substitutable words. However, there were different emphases and adjectives in each paragraph so I deduced that the words had different meanings, dependent on the context within which they were used. Considering these different paragraphs suggests to me that people use the term in different ways.

David Cooper (1992) contrasted a distended notion of environment, where each person’s environmental concern is supposed to extend everywhere ‘from street corner to stratosphere’, with the idea of a ‘milieu’ in which a person belongs and which they make their own. Their environmental concerns will begin ‘at home’ with their environments and the networks of meanings with which they are daily engaged.

Activity 5 Which issues are yours?

Which environmental issues are yours? Look at the list below. It is extracted from the BBC News website (in 2005). I searched for ‘environmental’ and a long series of headlines appeared including those below. You could generate a similar list yourself. Notice the wide range of issues that are considered to have an environmental aspect.

Which of the issues mentioned in the news headlines below seem distant or close to you? Which issues interest or concern you? (If none of these do, then try generating your own list to widen your selection.) Select three examples and note why they are of interest or concern to you.

- New-look [greenest] road on award shortlist

- Fury as greenfield homes approved

- Call for changes to housing plan

- Sewage study creates red (River) Clyde

- Campaigners fight nuclear reactor

- Environment award for youngsters

- Gold mine sparks battle in Peru

- Timber scheme wins national award

- Formal warning for cement works

- Anti-social behaviour inherited

- What really goes into a nappy?

- Protests as furnace plan unveiled

- General Electric doubles spend on green agenda

- Azerbaijan’s post-industrial hangover

- Pollutant affects sex chromosome

- Climate change message for city

- Greenpeace opposes wind farm plan

- Biodiversity project gets funding

- Online campaign seeks fishing ban

- Protestors arrested at G8 summit

- River Jordan nearly running dry

- Eco-Islam hits Zanzibar fishermen

Discussion

Issues that seem distant to me are gold mining in Peru and Azerbaijan’s post-industrial hangover. Some that seem close are those about home building on Greenfield sites, environmental awards for youngsters and opposition to windfarms. Three examples of issues of interest or concern are:

- The idea of an award for ‘greenest’ roads. I am curious to know what is meant, and as a road and car user concerned about the impact of road building and use, I’m interested to hear more about what sounds like a move to limit detrimental effects.

- Greenpeace’s opposition to a windfarm plan also interests me because I lived for sometime in Denmark where a lot of energy is generated by wind turbines where there seems to be a lot less opposition to them. To me, windfarms provide a better alternative to power stations, which seem to have more damaging environmental effects (such as coal or nuclear). So I’m interested to know the nature of Greenpeace’s objections.

- The online campaigns seeking a fishing ban also interests me. My perspectives are both as a consumer of fish and someone who enjoys seeing fish and other freshwater and marine life in their natural habitat in different parts of the world. I am also interested in the role of the Internet in environmental decision making.

In doing Activity 4 and Activity 5 you will have encountered some different ideas about what constitutes ‘environment’ and ‘environmental’ and thought a little about what the terms mean to you and what aspects interest or concern you. But how will these terms be used throughout this course?

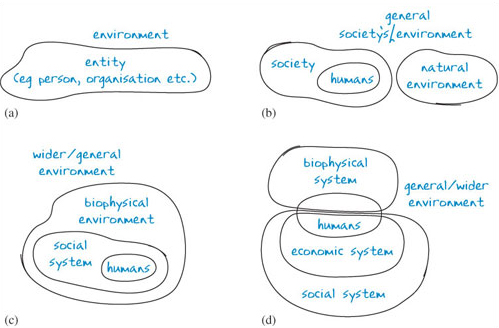

The environment of an entity can usually be described as that which surrounds it, affects it and in most cases is affected by it. The entity concerned may refer to an individual (as in my environment) or a group of living and/or non-living things (as in an organisation’s environment). Used in its narrow and ‘natural’ sense ‘the environment’ often refers to our biophysical surroundings. But humans are part of nature. People are in continuous interaction with their environment as they depend directly or indirectly on it for food, water, air and shelter for their very existence. It is our life-support system and at times its physical elements will be part of us. As well as sharing our environment with other people, we share it with other living things (both animals and plants) on which we depend.

However, the relationship between people and their environment has many dimensions – physical, biological, social, psychological, emotional, economic, even temporal – in terms of how we are currently affected by past decisions and how our decisions will affect us and other generations in the future. This unit will generally use ‘environment’ in this broad sense acknowledging its many dimensions.

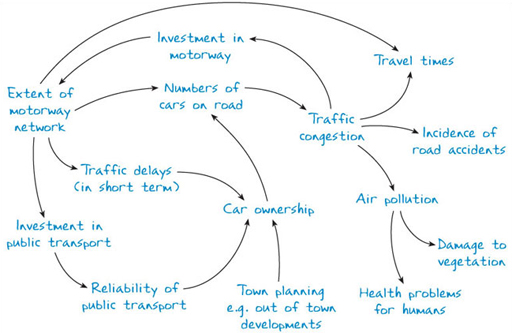

One useful way of representing the relationships between entities and their environment is to use a diagram – in this next case a systems map. Click on the following link to view a PDF on this diagramming technique.

Figure 2 uses systems maps to represent some different interpretations of the word environment and to experiment with boundaries. It is deliberately in draft form as it is trying to capture and represent a series of ideas about the concept of environment, from different perspectives, rather than showing a situation at a particular moment in time or a single system of interest, which would have a clear whole system boundary.

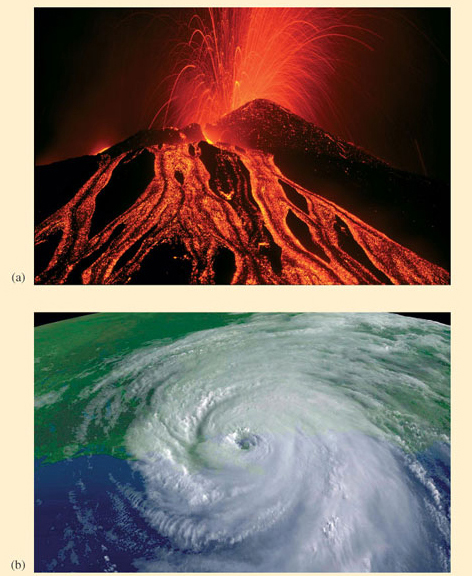

There is much criticism of anthropocentric (human-centred) definitions of ‘the environment’ because they emphasise its utility value to people rather than recognising it has value in its own right (i.e. intrinsic or inherent value). These definitions also fail to recognise the way in which people are always in their environment not able to be separated from it. Human-centred definitions are also often thought to imply control by humans of physical and biological processes that we cannot control. They also fail to acknowledge the many feedback loops in our relationship with our environment. However, humans exist in societies, most of which use technology, and we certainly have the ability to affect some natural processes in our use of that technology, depending on how we choose to use it. For example, temperature, rainfall, sea levels and the composition of the atmosphere have all been affected by people’ s activities, such as burning fossil fuels for energy and transport or changing land use. Our use of ‘green’ technology, e.g. for renewable energy, might have less effect on natural processes, depending on how it is used (Figure 3).

There are many possible choices about how we live and these choices are not simple to make, not least because the organisation of human societies is experienced by many as complex. Humans also affect and are affected by their environments just by living – breathing, eating, drinking, producing wastes, etc. – not only in their use of technology. In order to understand better the effects of our decisions and actions and how we might make necessary changes there is therefore a need to focus on what surrounds and affects humans, as well as their relationships with their environments. But it is important to keep in mind that there are many definitions of ‘the environment’ and to recognise that there are limits to what humans control (Figure 4).

2.2 Environment and system

We have already used the word ‘system’ in this unit several times. The word system is used extensively in our 21st Century vocabulary. For instance we refer to ‘the transport system’ or ‘a home entertainment system’ in a general way, not being specific about what we mean by system. Figure 2 used draft systems maps to explore some of the relationships in different definitions of ‘environment’. It shows ‘systems’, their sub-systems and their boundaries with the system’s environments. In experimenting with these diagrams we used the term ‘system’ in a different way from the general sense, to think in terms of systems. For now, you should note that it was possible to focus on some different systems, boundaries and environments in the different definitions, even though they started with the same word. Consider these further examples of systems from Sir Geoffrey Vickers, who was thinking of a school as a system:

A school is a physical system which even small children can represent by a map. Its buildings are spatially related to each other. It has an apparent perimeter, but this dissolves on examination. For it is intersected by sewers, water mains, power lines, roads, each of which makes it part of some other system. To the school these are its physical support sub-systems. But to those who manage these supporting systems, the school is a component, making demands but also subject to demands, such as for example the demand to economise water in a drought. It may not readily occur to a child or even a teacher that for other professionals as estimable as they the school may properly be regarded as a generator of sewage. ... A school is far more than a physical system, supported by other physical systems. It is also an educational system, a social system, a financial system, an administrative system, a cultural system, all with an historical dimension.

A system is not a fixed entity but the boundaries are identified by the observer and linked to purpose. Using the idea of a system raises some challenges for our use of the term ‘environment’. Identifying the school’ s environment, if thinking of a school as a system, becomes a specific exercise of judging what lies within the system and what lies in its environment and the boundary between the two will vary with the observer’ s perceptions and articulation of the system’ s purpose.

Systems concepts and techniques have been found useful by many for identifying what is relevant in a particular situation and what may be changed. They are an essential part of this course and using the concept of system/boundary and environment is at its core.

In general terms there are some simple principles implicit in the idea of a system:

- A system is an assembly of components connected together in an organised way.

- The components are affected by being in the system and are changed if they leave it.

- The assembly of components does something.

- The system has been identified by someone as being of interest.

2.3 Characterising environmental decisions

Ken Sexton and his colleagues wrote a book called Better Environmental Decisions – Strategies for Governments, Businesses and Communities (Sexton et al., 1999) in which they characterise environmental decisions (see Table 2). They had a particular purpose in mind in doing this:

Although the list is not exhaustive, it offers insight into the formidable task of categorising and evaluating different types of environmental decisions.

They structured their table around six dimensions:

- At what social level does the environmental decision occur?

- What are the important substantive aspects of the environmental decision?

- What is the social setting for the environmental decision?

- What is the mode of environmental decision making?

- What are the assumptions about underlying causes of the environmental problem?

- What criteria are used to evaluate the environmental decision?

suggesting that

Answers to these and related questions allow us to determine which disciplinary approaches, analytical methods and decision-making tools are most appropriate for evaluating and improving specific decisions. But we must recognise that the categories and sub-categories in Table 2 are artificially systematic and unrealistically precise devices that allow us to construct an easy-to-apply framework for conceptualising the important components of environmental decision making. The simplified framework, whilst useful, cannot completely describe the complexity and interconnectedness of many real-world decisions.

| I | Social Level of the Environmental Decision | |

| 1 Individual | 3 Organisation | |

| 2 Group | 4 Society | |

| II | Substantive Domain of the Environmental Decision | |

| A Type of issue | ||

| 1 Air quality control | 7 Urban infrastructure/growth management | |

| 2 Critical natural areas | 8 Waste management | |

| 3 Energy production/distribution | 9 Water allocation | |

| 4 Green technologies | 10 Water quality control | |

| 5 Natural resource management | ||

| 6 Historic, cultural and aesthetic resources | ||

| B Spatial extent | ||

| 1 Socially constructed scales, e.g. neighbourhoods, cities, states, countries | ||

| 2 Natural system scales, e.g. watersheds, airsheds | ||

| 3 Geologically based scales, e.g. plains, valleys, continents, earth | ||

| C Temporal factors | ||

| 1 Persistence | 3 Cumulative effects | |

| 2 Reversibility | 4 Context (past, current, future decisions) | |

| III | Social Setting for the Environmental Decision | |

| A Key Decision Maker | ||

| 1 Individual acting as an independent agent | ||

| 2 Individual acting as a member of a group or organization | ||

| B Decision Participants | ||

| 1 Governments | 4 Environmental advocacy groups | |

| 2 Regional governmental organizations | 5 Community/neighbourhood groups | |

| 3 Business associations | 6 Affected or interested individuals | |

| C Urgency of decision | ||

| 1 Urgent | ||

| 2 Deliberative | ||

| IV | Modes of Environmental Decision Making | |

| 1 Emergency action | 4 Elite corps | |

| 2 Routine procedures | 5 Conflict management | |

| 3 Analysis-centred | 6 Collaborative learning | |

| V | Assumptions about Basic Underlying Causes of Environmental Problems | |

| 1 Lack of scientific knowledge and understanding about natural systems or impacts of technology | ||

| 2 Imbalanced or inappropriate economic incentives | ||

| 3 Misplaced belief system and core values | ||

| 4 Failure to use comprehensive approaches (overly narrow perspective) | ||

| VI | Criteria for Evaluating Environmental Decisions | |

| A Decision process | ||

| 1 Fair | 3 Informed | |

| 2 Inclusive | ||

| B Decision outcome | ||

| 1 Workable | 4 Efficient | |

| 2 Accountable | 5 Equitable | |

| 3 Effective | 6 Sustainable | |

Activity 6 Engaging with multidimensional characteristics

Look at Table 2 above from Sexton et al. (1999):

- (a) Are there any words in the table that are not familiar to you? If so, list them to look them up in a dictionary or online search, or make a note to come back to them when you have finished the unit and see if their meaning has since been made clear.

- (b) Sexton et al. use the (italicised) categories of level, domain, setting, mode, assumptions and criteria in grouping dimensions of characteristics of environmental decision making. Work through each category selecting some of the levels, domains, settings and modes you have direct experience of and which assumptions and criteria you have come across before. Given that the list of categories and sub-categories is not intended to be comprehensive, are there any you would add?

Discussion

- (a) I have come across all the terms in the table before but I do wonder what the authors mean by words such as ‘elite corps’, ‘deliberative’, ‘natural systems’, ‘persistence’ and ‘critical natural areas’. There is some qualification of these terms in the text of their book, so I have either looked these up there or made some assumptions about what is meant:

- Elite corps – seems to refer to senior members of responsible organisations. This mode of decision making is one where those who do not fall into that category do not participate in the decision process.

- Deliberative – organised for a process of deliberating or debating, which as it’s in a category about urgency implies a longer time period is available than the ‘urgent’ category.

- Natural systems – I assume here that ‘natural’ as opposed to ‘manufactured’ is meant and that system refers to an assembly of interconnected components that does something. But I’m aware that ‘natural’ and ‘made’ distinctions often get blurred and ‘system’ is often used in a vaguer sense. The examples given regarding ‘natural system scales’ in the table are watersheds and airsheds, and while water and air are what I think of as ‘natural’, there is a lot about their use and management that isn’t. I wasn’t familiar with the term ‘airshed’ (other than as sheds that house aircraft!) so I looked it up and found it to mean an area where common weather conditions behave in a coherent way with respect to air pollution in the atmosphere. As such it provides a unit for analysis or management in the way that a water catchment area does. My understanding of ‘watershed’ in this context is also what I would think of as a water catchment, i.e. an identifiable area rather than a boundary. My understanding is that terms such as watershed, water catchment and airshed are used in a range of different ways in different countries and traditions.

- Persistence – I presume this refers to elements that persist over along time rather than breakdown, as with radioactive particles or some kinds of pesticides.

- Critical natural areas – I assume this refers to ‘critical’ in its ‘crucial’ rather than its ‘finding fault’ or ‘evaluating’ senses. But critical for what? Looking it up in their book, I note that Sexton et al. have given a definition as ‘issues concerning the protection of are as such as coastlines, floodplains, wetlands, ecological bio-reserves, parks, and the habitats of endangered species’.

- (b) A few examples of dimensions I have direct experience of:

- Levels – all the social levels;

- Domain – issues of critical natural areas and natural resource management: neighbourhoods (villages) and countries, watersheds; persistence (nuclear power issues) and context (my interest in ‘trajectories’ of decisions which in corporate past, present and future);

- Setting – individual acting as member of an organisation; environmental advocacy groups, community groups and affected or interested individual; urgent and deliberative decisions;

- Modes – emergency action, routine procedures and collaborative learning;

- Assumptions – I have come across all the assumptions about basic underlying causes of environmental problems (though I’m not entirely sure what’s behind ‘failure to use comprehensive approaches’ so would need to check that one);

- Evaluation – I have also come across all the evaluation criteria.

From my own experience I would add ‘multi-agency’ as a social level of the environmental decision. I would add ‘rural’ tour ban infrastructure/growth management from a UK context, and I would add ‘ethical’ to the criteria for evaluating environmental decisions.

2.4 Environmental decision making in the context of sustainable development

In simple terms, environmental decision making is taken to mean decision making that has an effect on our environment, however it is defined. If adopting a broad definition of environment, it could be said that nearly all decision making comes into this category. So why do we need to talk about environmental decision making at all rather than simply decision making? It is because there is increasing recognition that many of the decisions we make and actions we take, both individually and in groups, have an effect on our environment and yet economic and political considerations often dominate in a way that seems to exclude environmental considerations. By environmental in this context, I mean that which surrounds and affects us including our physical and biological life-support base alongside social, economic, cultural, political and institutional factors.

We are mainly taking into consideration those decisions which have local dimensions but are related to worldwide environmental issues, and where individuals and groups have choices they can make to maximise positive environmental outcomes, improve our environment and limit detrimental effects. Examples include our use of transport, making consumer decisions, planning new or improved developments and managing natural resources.

Whilst accepting that there are widely divergent views about what environmental decision making implies, we believe that the main challenge seems to be not one of replacing economic, political and social considerations, which currently prevail in much decision making, with an environmental agenda but one of bringing these factors together in every decision-making process. A note of caution is needed however: singling out one area for special attention might on occasions have the effect of separation rather than integration. In order that we might more fully explore this integration of environment with the other factors prevalent in decision making, we perhaps need to begin by taking the position that we cannot afford to exclude environmental concerns if we are to meet basic human needs both now and in the future. This is based on an assumption that the rate at which we are using some of our natural resources (such as oil, water or land) and polluting air, soil, fresh waters and oceans is unsustainable. Hence we will consider environmental decision making in the context of sustainable development and will now go on to explore what that means.

2.5 Sustainable development

2.5.1 Development

‘Development’ is another term that is used frequently in the context of environmental decision making. Like the term ‘environment’, it is a word that has many different meanings and understandings. One of its original meanings was as a biological notion synonymous with the natural progression of growth and differentiation to a stage of maturity. We will use it in several different ways:

- In a general sense, to denote progress or the gradual unfolding and filling out, usually used in a positive sense. For example, ‘the development of a proposal’ or the ‘personal development of an individual’.

- To refer to plans. Development plans, which often refer to built structures, have come to have a specific meaning and connotations because in many countries they are subject to legislation and regulation. For example, in the UK development plans are covered in a range of planning acts, regulations and guidance documents including The Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004, The Town and Country Planning (Local Development) (England) Regulations 2004 and The Town and Country Planning (Transitional Arrangements) Regulations 2004 and Planning Policy Statement 12 (PPS12): ‘Local Development Frameworks’ 2004.

- To describe particular site-based infrastructural projects, such as roads, buildings and dams, in the sense of ‘new developments’ or redevelopments.

- To refer to ‘world’ development, where there is also a range of different perspectives:

Development can be seen in two rather different ways: (i) as an historical process of social change in which societies are transformed over long periods and (ii) as consisting of deliberate efforts aimed at progress on the part of various agencies, including governments, all kinds of organisations and social movements.

Development is not synonymous with economic growth, though the two are often confused. Economic growth refers to a quantitative expansion of the prevailing economic system. Development is a qualitative concept which incorporates ideas of improvement and progress and includes cultural and social as well as economic dimensions.

In the context of environmental decision making, the term ‘development’ is often used with the adjective ‘sustainable’.

2.5.2 Sustainable development

Several events in the 1970s and 1980s emphasised the global nature of environmental issues and the links between environment and development, which in turn led to the emergence of the concept of sustainable development. These events included:

- the production of the World Conservation Strategy in 1980 (by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP);

- the Brandt Commission on North/South relationships, chaired by the former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, which reported in 1983;

- the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), which produced the report ‘Our Common Future’ in 1987 – also known as the Brundtland Commission, after Gro Harlem Brundtland, the then Prime Minister of Norway, who chaired the Commission. The Brundtland definition of sustainable development became particularly well known:

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

This definition embraces at least three concepts that can be interpreted differently by different individuals: those of development, needs and intergenerational equity.

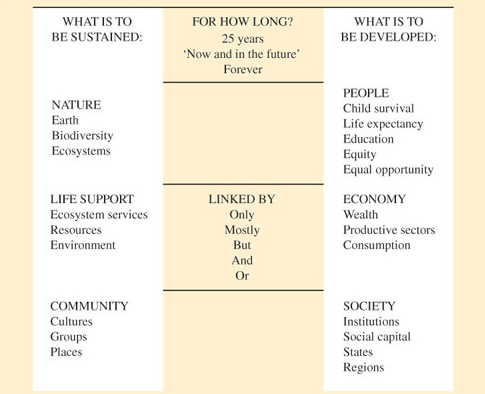

There have been many more definitions of sustainable development suggested since 1987. Figure 5 is a diagrammatic representation of one that came from the US National Research Council, Policy Division in 1999 (reproduced in Kates et al., 2005).

The ‘linked by’ section in Figure 5 refers to the different emphases in combining what is to be sustained with what is to be developed ranging from ‘sustain only’ or ‘develop mostly’ to combinations of what is to be sustained and developed using words such as but, and/or.

Activity 7 Concepts associated with sustainable development

List all the concepts included in the definitions of sustainable development given in this section so far, including Figure 5 (by concepts I mean ideas or notions, usually captured by key words or phrases, e.g. ‘development’ or ‘life expectancy’).

Discussion

The Brundtland definition incorporates the concepts of development, needs and intergenerational equity. The US National Research Council definition includes concepts of nature (earth, biodiversity and ecosystems), life support (ecosystem services, resources and environment), community (cultures, groups and places), people (child survival, life expectancy, education, equity, equal opportunity), economy (wealth, productive sectors, consumption) and society (institutions, social capital, status, regions).

However it is defined, sustainable development is a concept that has been in use since the mid 1980s and is still very much in evidence. Many people have at least partially accepted it, as was shown by the work done before, during and after the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) – the Earth Summit – in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg. (Both of these initiatives will be discussed later in this section.)

Does it matter that the concept of sustainable development is open to interpretation? Is it important that people share an understanding of this concept or is it more a question of how people use it? Some people consider sustainable development to be a rather vague ideal with implications we have yet to understand, while others have used it to develop clear plans of action with achievable goals.

Here is one view from Sir Martin Holdgate when he addressed the UK Royal Society of Arts in 1995 in his role as President of the Zoological Society:

My conclusion is that the concept of ‘sustainable development’ is less novel than has often been made out. It is, in fact, a synonym for ‘rational development’, because it is a process of making the best practicable use of natural resources for the welfare of people. Its goal must include economic advancement, and there seems no fundamental reason why market economic systems cannot be adapted to generate sound growth while conserving our environment. But the goal of sustainable development is to deliver quality of life, and here we must pause. For there are indefinable qualities in the world that are not easily susceptible to economic valuation, and can easily be swept aside by the tide of expediency. Yet the richness and beauty of nature and the wonder of great landscapes can fill the dullest mind with awe. The development process must value these things, too, and it will indeed be a test of success if a century from now a stable world human population enjoys a quality of life far better than today’ s average, in a world with something near today’ s diversity of plant and animal species. It can be done. It will not be easy. The slower we are in adapting the more costly and difficult it will be.

Here is another view from Wendy Harcourt from her book Feminist Perspectives on Sustainable Development:

Development = economic growth is at the centre of development discourse. Even though many commentators point out that development is far more than economic growth but extends to social, political, cultural, environmental and gender concerns, economic growth remains firmly entrenched as the stated goal of development from which modern critiques of development begin.

Over the last few years, this approach to development had been criticised and challenged by a number of development economists interested in revising economic theory and methodology to include environmental considerations. They have been joined by development professionals concerned that poverty alleviation and the basic needs approach of development programmes are not bringing about the hoped-for end to mass poverty and environmental deterioration. Women working in development are also part of this debate in their argument that the fundamental gender bias of development thinking and practice prevents gender equity and ignores women’ s contribution to the economy and their role in the management of the environment. And radicals in both industrialised and developing countries enter into the debate questioning the whole modernisation process and Western knowledge systems on which development is based.

These thinkers and activists have found their voices in the recent policy debates on environment and development labelled ‘sustainable development’. They have used the political platform created by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED)... to bring their particular concerns about the thesis that development = economic growth to the public arena.

Activity 8 What does sustainable development mean?

- (a) Read the two quotes from Sir Martin Holdgate and Wendy Harcourt. Make a list of the words or phrases that strike you as particularly relevant to the concept of sustainable development. (You could begin with your answer to Activity 7 if you find it difficult to start this activity.)

- (b) Look at your list and try to group similar or related words together. Write alongside them what train of thought you were following. (Do not try to use all the words.)

- (c) Write a couple of sentences about your own perspective in relation to Holdgate’s and Harcourt’s. Do you identify with any of the points they have made through your own experience?

Discussion

- (a) sustainable development; rational development; natural resources; welfare of people; economic advancement; market economic systems; sound growth; conserving our environment; quality of life; indefinable qualities; world; economic valuation; expediency; richness and beauty of nature; wonder of great landscapes; development process; test of success; stable world human population; diversity of plants and animal species; it can be done; won’t be easy; adapting; costly; difficult; economic growth; development discourse; social, political, cultural, environmental and gender concerns; critiques of development; criticised and challenged; include environmental considerations; development professionals; poverty alleviation; mass poverty; environmental deterioration; gender bias of development thinking and practice; management of the environment; questioning the whole modernisation process and Western knowledge systems on which development is based; thinkers and activists have found their voices; political platform created UNCED; bring their concerns to the public arena.

(b) My train of thought – economic?

Economic advancement; market economic systems; economic valuation; costly; economic growth.

My train of thought – what adjectives?

Rational; sound; indefinable; world; economic; development; value; stable; costly; difficult; social, political, cultural, environmental; mass; whole; Western; public.

My train of thought – how?

Economic advancement; sound growth; expediency; value; it can be done; won’t be easy; adapting; critiques of development; criticised and challenged; include environmental considerations; poverty alleviation; management of the environment; questioning the whole modernisation process and Western knowledge; bring their concerns to the public arena.

- (c) One gap I noticed was that the perspectives of young people seem to be missing, although the Agenda 21 process and those that succeeded it did include ‘youth’ as a major group. There is also something about quoting from articulate people who have written their contributions, or had their words written down and reported, that makes me wonder whether there is a big gap in terms of the perspectives of the many people who do not communicate much in text, or who have never heard of the concept of sustainable development but still might make points for and against it if they had the chance. Perhaps some of the issues that might be of concern to them are here but how can I tell if I do not hear from them directly?

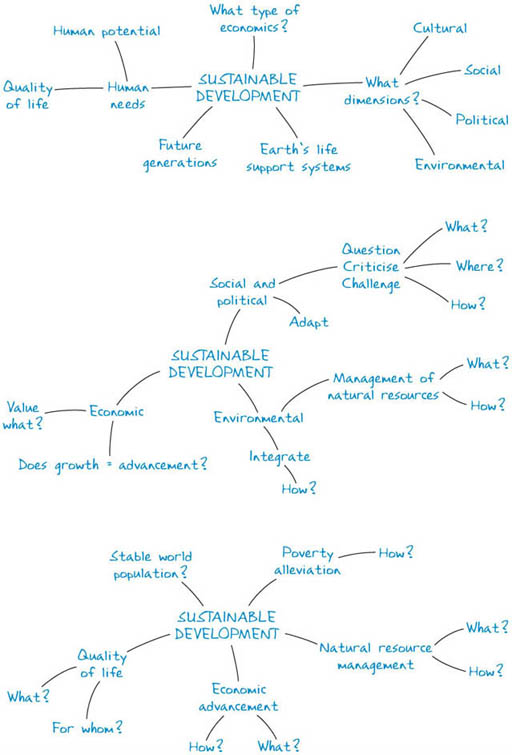

Activity 9 Raising questions about sustainable development

Now use your answers to Activity 7 and Activity 8 to focus on those aspects of sustainable development that raise questions for you so that you can pursue them later on. Use one or more spray diagrams to help you clarify, organise and develop your thinking. If you have not used spray diagrams before, first read through Box 1 and then follow the guidelines in the PDF below.

Discussion

Box 1 Why use diagrams?

Diagrams have already been used in this unit but this is the first time we are asking you to draw your own, which is why this box appears here.

Diagrams can help you to clarify, organise and develop your thinking and to explain to others how you are thinking. They also enable you to represent simultaneous processes or ideas, in a way that is very dif. cult in sequential prose. They can be used to help simplify and summarise a complex situation, which has the advantage that it can make it easier for others to understand and the disadvantage that in selecting what you include and leave out you oversimplify a situation, which can mislead.

One point to note is that the process of diagramming is often more important than the product. Think carefully about the purpose of your diagram. If it is to be used to communicate your thoughts to other people, you may need to show them the stages you have gone through, not just the final product. Where you have included opinions and judgements for your own purposes, you may need to prepare an edited version before you show it to others. You will also find it helpful to give a meaningful title to your diagrams. You will use diagrams in this course in two ways: firstly by drawing your own; secondly by interpreting those drawn by others. These are two separate but linked skills. Critical consideration of the nature of a diagram drawn by someone else can help to develop your own diagramming. There are many different types of diagram and many different ways in which they can be used. More will be said about these in later books.

2.5.3 United Nations initiatives for sustainable development and decision making

Out of UNCED emerged conventions on climate change and biodiversity, a set of guidelines of forest principles, a declaration on Environment and Development, and an extensive international agenda for action for sustainable development for the 21st Century – Agenda 21. From WSSD came reaffirmed commitment to sustainable development, including a declaration that committed to ‘a collective responsibility to advance and strengthen the interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars of sustainable development – economic development, social development and environmental protection – at local, national and global levels’ (the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, 4 September 2002). WSSD also produced a plan of implementation. Between these two international Summits came the UN’ s Millennium Summit when Heads of State adopted a series of goals with targets concerning peace, development, environment, human rights, the vulnerable, hungry and poor, Africa and the United Nations.

These initiatives are inter-related and each has built on what had been done before. Their significance for environmental decision making is that, in common with some other international initiatives, they have attempted to address issues that cannot be addressed at just one level (local, national or regional). National-level programmes (e.g. Local Agenda 21 (LA21) programmes) have been linked to the international level. In all three of the UN Summit processes, concerns about and recommendations for decision making were included.

Agenda 21 was developed well over a decade ago, for UNCED in 1992 (Quarrie, 1992), but it had a long-term horizon with targets for implementation and monitoring of progress and dealing with changing priorities that took place through the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development. It therefore became an ongoing process and although the language of Agenda 21 is less in evidence now than it was in the 1990s many of the principles and agreements reached in the Agenda 21 process are still relevant.

Agenda 21 was published in some 40 chapters, each presented with a basis for action, objectives, activities and an estimate of financial costs. It had four main focuses:

- Social and economic dimensions

- Conservation and management of resources for development

- Strengthening the role of major (stakeholder) groups

- Means of implementation

Two chapters to note in the context of this course are:

- Chapter 8, ‘Integrating environment and development in decision making’, which considers integrating environment and development at the policy and management levels, providing an effective legal and regulatory framework, making effective use of economic instruments and market and other incentives, and establishing systems for integrated environmental and economic accounting.

- Chapter 40, ‘Information for decision making’ , which considers bridging the data gap between the so-called ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ worlds, and improving availability of information that could be used for the management of sustainable development.

After UNCED the many recommendations in Agenda 21 were taken up in varying degrees. There was a series of issues around implementation ranging from finance to participation. However, many people worldwide were involved in the overall process of Agenda 21 and it has been a major focus in many different countries for a great deal of activity on environment and development. LA21 programmes were developed in several countries.

In September 2000, at the UN Millennium Summit, 147 Heads of State and Government agreed to a set of development goals, with targets, for combating poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation and discrimination against women. These goals became known as the Millennium Development Goals (see Box 2).

Box 2 The Millennium Development Goals

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger:

- Reduce by half the proportion of people living on less than a dollar a day;

- Reduce by half the proportion of people who suffer from hunger.

- Achieve universal primary education:

- Ensure that all boys and girls complete a full course of primary schooling.

- Promote gender equality and empower women:

- Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015.

- Reduce child mortality:

- Reduce by two-thirds the mortality rate among children under five.

- Improve maternal health:

- Reduce by three-quarters the maternal mortality ratio.

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- Halt and begin to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS.

- Halt and begin to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases.

- Ensure environmental sustainability:

- Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes; reverse loss of environmental resources.

- Reduce by half the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water.

- Achieve significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers, by 2020.

- Develop a global partnership for development:

- Develop further an open trading and financial system that is rule-based, predictable and non-discriminatory. Includes a commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction – nationally and internationally.

- Address the least developed countries’ special needs. This includes tariff- and quota-free access for their exports; enhanced debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries; cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous official development assistance for countries committed to poverty reduction.

- Address the special needs of landlocked and small island developing states.

- Deal comprehensively with developing countries’ debt problems through national and international measures to make debt sustainable in the long term.

- In co-operation with the developing countries, develop decent and productive work for youth.

- In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries.

- In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies – especially information and communications technologies.

A further plan of implementation of action for targeting specific areas of sustainable development emerged from the World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002.

From the Johannesburg WSSD process came a range of outcomes including:

The Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, the official declaration made by Heads of State and Government

The Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, negotiated by governments and detailing the action that needs to be taken in specific areas

Type 2 Partnership Initiatives, commitments by governments and other stakeholders to a broad range of partnership activities and initiatives, adhering to the Guiding Principles, that will implement sustainable development at the national, regional and international level.

An explicit reference to decision making was made in the Johannesburg Declaration:

We recognise that sustainable development requires a long-term perspective and broad-based participation in policy formulation, decision-making and implementation at all levels.

Decision-making processes, including environmental decision making, are implicit in ideas of public– private and other multi-agency partnerships which are mentioned both in the Millennium and the Johannesburg Declarations. As ‘Ensuring environmental sustainability’ is one of the eight Millennium Development Goals (see Box 2), environmental decision making is also implicit.

Activity 10 Environment and the Millenium Goals

How is the term ‘environment’ used in the Millennium Development Goals?

Discussion

Three bullet points are included under the ‘environmental sustainability’ goal. All three seem to assume anthropocentric definitions of ‘environment’. The first is about integration of sustainable development into country policies and programmes with an emphasis on reversing loss of ‘environmental resources’. It is not specific about which resources, but given the context of the goal I assume that it is linked to issues of livelihood. The second highlights ‘sustainable access to safe drinking water’ as a part of environmental sustainability and the third focuses on quality of life.

How does environmental decision making link up with decision making for sustainable development? Are they the same thing? The short answer is ‘No’. For example, a social services department might decide to use more transport to allow more people to have access to basic services. This decision may be in direct conflict with their stated environmental aims to reduce transport-related emissions and yet it is in some ways a sustainable development improvement. This single decision is focused more on social sustainability than environmental sustainability. However, a social services department committed to sustainable development might, as a whole, make a series of trade-offs between environmental, social and economic considerations, so it is misleading to consider the single decision out of context.

I mentioned previously that the focus on environmental decision making in this course is to ensure that environmental considerations are not forgotten. However, I also pointed out the need to integrate environmental, social and economic considerations. In some cases this means that decisions can be made that have positive effects in all three of these areas, such as the win– win situation of an environmental business that provides employment. In other situations it means choices between one aspect and another, involving trade-offs, as in the example of the social services department. Sustainable development is the context for environmental decision making.

In some cases, LA21 programmes were adopted by governments, authorities and organisations that had already developed environmental policies and plans. For instance, nearly all UK local authorities produced LA21 strategies by the end of 2000, although they did vary in form and quality (Webster, 1999). The process they have had to go through to change course from a focus on environment to one on sustainable development has generally been one of moving out boundaries to include a broader range of both people and ideas in decision making. The UK Local Government Act 2000 meant that UK local authorities had a duty to promote economic, social and environmental well-being and sustainable development of their areas in their community planning although they did not have the power to raise money specifically for this activity. Environmental decision making can take place within the context of sustainable development. The process needs to start with groups of people thinking critically and systemically and working out what is relevant in a particular situation, rather than trying to think about everything at once.

The way that the use of the sustainable development concept has brought people with environmental, social, political and economic agenda into the same forums for discussion and action is a very important part of the context of environmental decision making.

3 Values, power and evolving discourse in environmental decision making

3.1 The importance of values

The values of decision makers were briefly mentioned in previously in the unit as a factor that influences decisions. Value is used here not in its numerical sense, but to mean something that an individual or group regards as something good that gives meaning to life. Values can also be thought of as deeply held views, of what we find worthwhile. They come from many sources: parents, religion, schools, peers, people we admire and culture. Examples of values an individual may hold are those associated with: creativity, honesty, money, nature, working with others.

Activity 11 Identifying your values

Write down three values that are important to you. Give an example of how one of these values affected your recent decision making.

Discussion

Three values of the kind suggested that are important to me are to do with nature, diversity and equality. While I find it fairly easy to identify these in a general sense, the detail of these values only becomes evident when I consider how I think and act in a particular situation.

In recent decision making, my valuing of ‘nature’ was a key factor in how I spent my time at the weekend, walking in the countryside. I am wondering about what I mean by ‘nature’. (I am thinking of places where trees, flowers, birds and animals thrive and where I can see the sky and rural landscapes.) I also wonder if my example suggests a value that has more to do with ‘experiencing nature’ than actively doing something about enabling it to thrive!

Values that affect decision making may be collective as well as individual. The following set of values has been identified by a collective process as those underpinning the United Nations Millennium Declaration. They are clearly thought by a group of people, not just an individual, to be important.

Activity 12 Recognising consistency in values

Read through the values underlying the Millennium Declaration in Box 3. Bearing in mind that this is only part of a document, and that objectives to translate these shared values into actions were also listed in the document, do you find that these values are consistent with each other, or not? Write a few sentences highlighting some examples of any consistencies or anomalies you find.

Discussion