👉 Find out about The Open University's Geography courses. 👈

Social decline in the West of Ireland was not, however, just a local or regional problem. It was a national political issue. Although peripheral to modern social and economic development, the West was of central importance in the realm of Irish politics as the repository of cultural survival and rural ideals which were fundamental to Irish nationalism, statehood and independence. The Irish Folklore Commission, set up in 1935, collected stories extensively from local people in the West of Ireland, especially from Irish speaking areas. The older people especially, were seen as the repository of an ancient tradition that was under threat but was vital to preserve. Another important source was the 1938-9 Schools Collection, where pupils of the National Schools recorded stories from the people of their area (University College Dublin, n.d.).

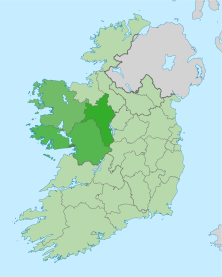

For the West to be declining was an affront to the national image, challenging such key elements of Irish culture as religion, the language and the family farm. Decline and the population appeared synonymous, and it was in the West that the losses were greatest as can be seen in the map, population decline in the West between 1891 and 1961 was commonly over 40%.

Imagine that you were travelling across Ireland observing not landscape but how population change had affected the country. Using the map and moving on a line north west from Dublin (A to B) describe the pattern you observe. The aim is to gain an impression of the impact that population decline can bring to an area. (Map source)

Emigration and employment

It was in the national political interest that emigration be stemmed. The factor most closely linked with emigration and decline was employment, so saving the West meant creating jobs in the West. Even with considerable structural reform, agriculture was unlikely ever to provide sufficient jobs and the obvious answer seemed to lie in industrialisation. However, most of the manufacturing industry attracted to Ireland in the 1950s and 60s had located in Dublin, the main ports and a few of the larger towns. This created a new pattern of rural to urban migration within Ireland that took the place of some of the traditional emigration from Ireland, so the West still experienced a loss of population.

"The factor most closely linked with emigration and decline was employment, so saving the West meant creating jobs in the West."

As a result, in the mid-1960s the government sponsored Industrial Development Authority (IDA) was charged with taking jobs to the people which meant attracting employment to areas outside Dublin and the other major centres, and especially to the West. Many of the firms successfully attracted to the West by the IDA were foreign-based, mainly in Britain and America but also Germany and Japan. They were certainly drawn by the government incentives, but also by location relative to the EU and by ‘green labour’, a workforce with no prior industrial experience or skills. This ‘green’ labour existed largely because Ireland had not been industrialised in an earlier period.

So labour, which had for generations migrated from Ireland to the centres of industrial capitalism, became a major factor in a new pattern of industrial location. The West of Ireland which had long exported labour, now imported jobs. In other words the failure of the region within the previous economic order became an attraction within the new: apparent disadvantage became advantage; but in the not altogether flattering terms of the non-unionised tradition and low expectation in wages. In short, one layer produced conditions for the next.

Modernisation

In the West of Ireland a history of rural poverty and resulting emigration contributed to a spiral of social decline. This affected the traditional culture that was central to Irish nationalism, which in turn is of central importance to the existence of the Irish state. In this sense, the state as a whole is dependent on a cultural identity which survives most strongly in the West. To prevent further social decline in the West, the state-sponsored modernisation through industrialisation, has paradoxically endangered the surviving traditional culture.

Industrialisation has also opened the West of Ireland to a new interdependence within the international economic system. Economic relationships have been important to the region’s interdependencies: for example, in agriculture, relationships with Britain and Europe have dominated; while labour, previously supplied to Britain and America is now an attraction to foreign industry. But industrialisation has not made the West the same as everywhere else. The combination of new, external factors with existing characteristics is unique. Central to the uniqueness of the region has been the survival, albeit in modified form, of elements of the traditional culture.

The introduction of new economic and social relationships through the political process of the wider society (and new layer) was affected by the local culture and became established as a unique combination of elements (although individual elements were also found elsewhere) and local characteristics. That new layer presents the conditions for the next layer. Through the process of change culture is modified as well as being a modifying influence. The landscape is modified also. These local changes occur through interaction with more general and widespread social processes.

This series of articles on The West of Ireland: Dimensions of distinctiveness has discussed various interacting processes which have all contributed to the unique and changing character of the West of Ireland.

- Make a list of the key processes which have been identified, noting an example in each case.

- Thinking of your own home place (or another area which you know well), now see if you can find parallel examples.

- Identify at least two examples of interdependence between the West of Ireland and the wider world.

References for this series

- E. Estyn Evans, (1957) Irish Folk Ways, p 268, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Irish Times (1943) 'RUNDALE IN COUNTY MAYO: 25 years' struggle ends', The Irish Times, Jan 12, 1943. [Online] http://search.proquest.com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/hnpirishtimes/docview/523275403/fulltextPDF/88B03FC8BB1C45BFPQ/1?accountid=14697

- Dale (2010) 'The Rundale System of Land Holding in County Mayo, Ireland', County Mayo Beginnings. [Online] http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~irlmayo2/rundale_system_mayo.html

- University College Dublin (n.d.) 'Schools’ Folklore Scheme (1937-38)', National Folklore Collection. [Online] http://www.ucd.ie/irishfolklore/en/schoolsfolklorescheme1937-38/

Acknowledgements

This material draws from an Open University course based on the work of Pat Jess.

-

Jess, P. (1985) ‘Unit 17 Local Change in the West of Ireland’, in The Open University (1985) D205 Changing Britain, Changing World: geographical perspectives, Broadcast Handbook, Milton Keynes, The Open University Press.

-

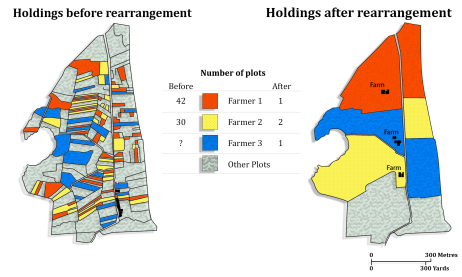

In 'The rural dimension – rundale in the West of Ireland' - Figure 8c ‘An example of the effects of reorganisation: Cloondeagh County Mayo’, p. 20

-

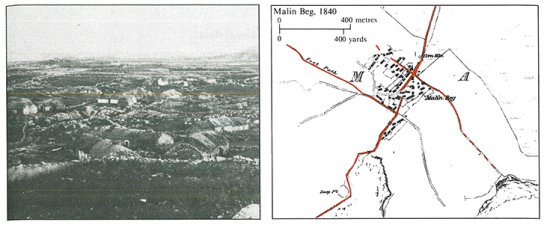

In 'The rural dimension – after rundale' - Figure 3 ‘Settlement and Landscape’, (a) Rundale cluster,(b) Dispersed farmsteads, (c) Ladder farms, p. 11

-

In 'A changing uniqueness – The changing ‘place’ of the West' - Figure 1 ‘The delimitation of the West of Ireland as a region’, p. 8

-

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews