There is often concern about the fact that we don’t seem to be able to get people to volunteer to run clubs and societies in the way that was once the case. David Cameron’s suggestion that he wished to appoint a ‘neighbourhood army’ which would consist of ‘5000 community organisers’ has failed to materialise. To account for the decline in civil engagement, people have suggested the culprits could be the development of the notion of the teenager male who did not wish to ape his father's habits, the growth of interest in social media, greater mobility and urban sprawl. It is women being in paid work, not baking cakes for the bazaar say some. It is men working long hours, commuting and then slumping in front of the television, not running the local Scout Troop, say others. The list goes on. Some have suggested that the ‘Big Society’ (to use a phrase associated with the Prime Minister) is being squeezed by the Big State.

There is often concern about the fact that we don’t seem to be able to get people to volunteer to run clubs and societies in the way that was once the case. David Cameron’s suggestion that he wished to appoint a ‘neighbourhood army’ which would consist of ‘5000 community organisers’ has failed to materialise. To account for the decline in civil engagement, people have suggested the culprits could be the development of the notion of the teenager male who did not wish to ape his father's habits, the growth of interest in social media, greater mobility and urban sprawl. It is women being in paid work, not baking cakes for the bazaar say some. It is men working long hours, commuting and then slumping in front of the television, not running the local Scout Troop, say others. The list goes on. Some have suggested that the ‘Big Society’ (to use a phrase associated with the Prime Minister) is being squeezed by the Big State.

A recent study made in the USA adds to the explanations for the weakness of voluntary associations, democracy and what has been term ‘social capital’ by arguing that the enforcement of stricter drink-drive legislation is a cause of the decline. This sounds like a cautionary tale of the unintended consequences of a public good. Worried by the prospect of getting stopped for being over the limit, people go out to drink less, they socialise less and their clubs, many of which raise large sums for charity, wither away.

There is anecdotal evidence that alcohol can lubricate sociability and collaborative learning. The scientist Sir Peter Medawar OM, CBE, FRS set up a bar specifically so that scientists would collaborate and build knowledge together. At the Open University, one of the founders, Jennie Lee, found some funding in order to have a cellar converted into a bar for staff at Walton Hall. It was felt that they were somewhat isolated on the greenfields site before most of the town of Milton Keynes was built and the aim was to ‘establish friendly contacts with members of the general public and other institutions in the area’ as the Vice Chancellor’s report put it.

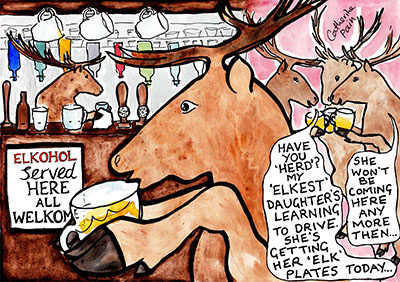

This latest study, by John C. Mero is called Under the Influence. A Case Study of the Elks, MADD, and DUI Policy (Lanham, Maryland, USA, University Press of America, 2015) and readers based in Britain may need a translation if they are to get to grips with the title. The Elks of the title refers to the US-based, men-only (until the 1990s) fraternal and charitable body, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. The acronyms stand for the legislation Driving Under the Influence and the advocacy group, Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the phrase ‘under the influence’ can refer both to the impact of alcohol and the role of MADD.

Social scientists might also be interested in Mero’s methodology. He considered relevant arrest rates and Elk membership rates over a 20-year period for 27 U.S. states. He examined the rise in the number and location of MADD Chapters and he spent a lot of time online, checking newspaper reports of drink-related stories and how MADD presents itself. He bulked out a rather thin book with lengthy reproductions of material which is available online. Perhaps most of the interest is the interview material. You might think that the observer would go down to these bars to imbibe a bit of the culture of these places but instead, he rang officers in the Elks. Some of the 55 ‘Exalted Rulers’ (the chair of the ‘lodge’ or branch) who he telephoned sound like they are drinkers eager to complain about the self-righteously sober. One is quoted as saying ‘I’m sitting at the bar getting a little inebriated’.

While some drinkers (and smokers restricted by bans) might take comfort from a theory that sophisticated, integrated lobbyists are pitted against the convivial and charitable, that the old ways are being undermined by women seeking retribution, Mero’s thesis, that social drinking can help build communities, might have been more convincing if he had compared the decline of the Elks with that of the teetotal Sons of Temperance. The Sons were, like the Elks, a popular fraternal body in the nineteenth and early twentieth-century America. Initially, only white men were members of the Elks and the Sons but both came to admit black men and then women. Membership of both has been in decline of late. While the drinkers might have withdrawn from civic life, disgusted that the government no longer trusts them, the same is unlikely to be the case with the advocates of temperance. Nevertheless, there is a wider message we might take from this. It is that this evidence from the USA suggests that if we wish to rebuild communities, renew social capital and encourage reciprocity we need to recognise that each person can have a variety of identities and that we take seriously not just that we need to meet but how we associate with one another.

This blog post is part of Society Matters. The blog seeks to inform, stimulate and challenge our understanding of this changing world and of our humbling role within it.

Want to know more about studying social sciences at The Open University? Visit the Social Sciences faculty site.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Society Matters posts are those of the individual authors, and do not represent the views of The Open University.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

First of all, studying those men-only clubs is not going to bring useful results. Membership of those things has (thankfully) declined probably because people are not so narrow-minded in that way anymore. They don't serve a function anymore.

Secondly, civic participation is still fine in many places. In certain locations it has declined significantly maybe because of a withdrawl of useful public services and places to go. Some people have never wanted to go to the pub. And many people can be co-operative and sociable without being a little bit drunk.

I would suggest David Camerson's suggestion for that army didn't materialise because people thought it was, like the majority of his 'social' ideas, farcical.

The article seems to exclude a huge proportion of society in its research and outlook.