8.1.2 Contesting political representation in Wales

Historically, several different groups have contested the system of political representation in Wales. For example, in 1925, Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru (later to be known as Plaid Cymru,) was established in defence of the Welsh language and to demand ‘freedom’ for Wales to decide on its own political affairs. Plaid Cymru, along with its Scottish counterpart, the Scottish National Party (SNP), played an important role in putting the issue of devolution onto the UK political agenda in the 1960s and 1970s. Partly in response to the growing electoral threat of Welsh and Scottish nationalism, the British Labour Party committed itself to a programme of devolution for new democratically elected bodies in Scotland and Wales. These plans were presented to Scottish and Welsh voters in a referendum in 1979.

Activity 23

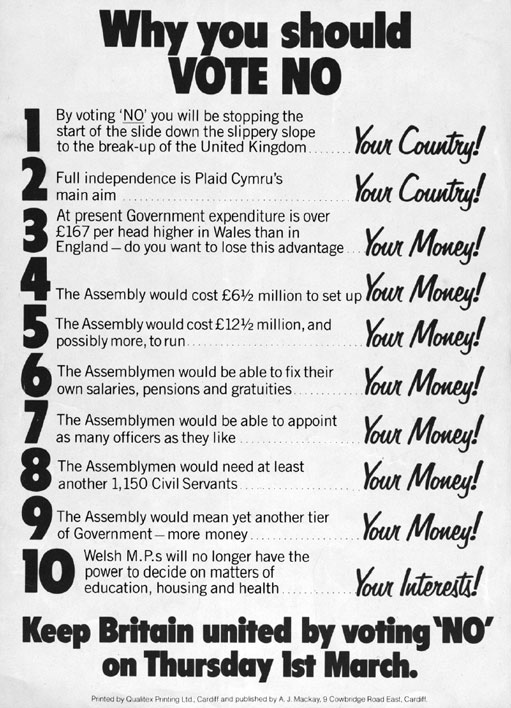

Figure 16 is a facsimile of a pamphlet summarising some of the main arguments put forward by opponents to devolution in the 1979 referendum on Welsh devolution. As you read it, consider how persuasive these arguments are, and what kind of arguments supporters of devolution might have made in response to these claims.

Discussion

You may agree or disagree with these arguments against devolution to Wales. But in 1979, those plans were firmly defeated. These results, and the election of a new Conservative government in 1979 which had little interest in such issues, meant the issue of devolution was off the British political agenda for several years. And yet, it was during the eighteen-year reign of the Conservative Party – from 1979 to 1997 – that concerns about the legitimacy of political representation in Wales grew to such levels that by the mid-1990s, there were renewed demands for devolving power to a democratically elected Welsh Assembly.

The concept of legitimacy is an extremely important term in politics, but it can be difficult to agree on a single definition of the term. One way of thinking about it is in terms of ‘rightfulness’ (Heywood, 2000, p. 29). So, for example, if we wanted to assess the legitimacy of a political system, we would want to know to what extent people living in that system think that the ways in which political decisions are taken are ‘right’. If a political system produces fair policy outcomes that are accepted and (in the case of laws) obeyed by the people living in the system, then we would say that this is a legitimate political system. This is because the members of the political community accept to be governed in a particular way, and obey the political decisions made by those that govern. A political system which lacks legitimacy would be one where there is a feeling that those in power do not have a right to take political decisions on behalf of people living in that community.

In order to help you think about the legitimacy of a system of political representation, it is helpful to think in terms of the ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ of any process of political representation (Judge, 1999, p. 21).

- The ‘inputs’ refer to elections, and here we are interested in the ‘rightfulness’ of the way in which representatives are elected (e.g. are the elections fair, open and transparent?), the degree to which representatives reflect the policy preferences of voters, and who the representatives are.

- The ‘outputs’ refer to what representatives do once they have been elected; here we are interested in whether or not our representatives have acted responsibly and in a way which corresponds to our preferences.

In Wales by the mid-1990s, it is arguable that political representation suffered from problems of both input and output legitimacy. With regard to input legitimacy, there were two main issues of concern. The first related to the political preferences of Welsh voters, and how these were reflected (or not) in the government that ruled in Westminster.

Table 2 provides the general elections results for Wales between 1979 and 1997. If you look in particular at the row for ‘Conservatives’, you will notice what happens to the party’s electoral results between 1979 and 1997. Compare this then to the row for ‘Labour’ and you will notice that the biggest difference in the electoral performance of these two parties is that the Conservative Party has never had an electoral majority in Wales.

| 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1992 | 1997 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats |

| Labour | 47.0 | 22 | 37.5 | 20 | 45.1 | 24 | 49.5 | 27 | 54.7 | 34 |

| Conservative | 32.2 | 11 | 31.0 | 14 | 29.5 | 8 | 28.6 | 6 | 19.6 | 0 |

| Liberal Democrats | 10.6 | 1 | 23.2 | 2 | 17.9 | 3 | 17.9 | 1 | 12.4 | 2 |

| Plaid Cymru | 8.1 | 2 | 7.8 | 2 | 7.3 | 3 | 8.8 | 4 | 9.9 | 4 |

| Others | 2.2 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 3.4 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 36 | 100 | 38 | 100 | 38 | 100 | 38 | 100 | 40 |

Footnotes

Thrasher and Rallings, 2007, p. 223.The Conservative Party’s levels of electoral support declined from 1983–1997. This is in contrast to the Labour Party, which strengthened its dominant position in Welsh politics over the same period of time. So, Wales was being governed by a political party that did not enjoy the support of Welsh voters. The growing frustration caused by this situation was expressed clearly by Ron Davies, Labour Party MP for Caerphilly and one of the main architects of Welsh devolution:

In 1987 and again in 1992 I clearly remember the sense of despair not only at the return of a Conservative government but the consequences of Wales having so clearly turned its face against the Tories yet still facing the prospect of a Tory government, a Tory Secretary of State and Tory policies imposed on us in Wales. I vividly recall the anguish expressed by an eloquent graffiti artist who painted on a prominent bridge in my constituency, overnight after the 1987 defeat, the slogan ‘we voted Labour and we got Thatcher’.

This feeling of being governed by an ‘unelected’ political party was aggravated by the fact that many secretaries of state appointed to the Welsh Office – and therefore affecting the substance and style of policy making affecting Wales – were MPs from English constituencies. Only one of the six Conservative Welsh Secretaries between 1979 and 1997 held a seat in Wales.

As far as output legitimacy is concerned, the Conservative Party’s policy decisions were frequently felt to be imposed on Wales against the will of the Welsh voters. This was aggravated by the fact that the Welsh Office was at times under the leadership of individuals – notably John Redwood – with pronounced Thatcherite views that were manifestly at odds with Welsh political values. Other policy decisions taken by the central government – including the poll tax and the privatisation of heavy industries such as coal – were also deeply unpopular. Conservative Party rule also oversaw the growth of so-called ‘quangos’ in Wales (quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations). These are independent bodies under the leadership of government appointees and responsible for regulating newly privatised industries, overseeing cultural and scientific activities and advising the government on policy. In Wales, this included bodies such as the Welsh Development Agency, the Welsh Language Board, the Welsh Tourism Board, and various regional Health Authorities. The growth of the quangos exacerbated the feeling that Wales was increasingly being governed by an ‘unelected state’ (Morgan and Mungham, 2000, pp. 45–67).

Add to these concerns about input and output legitimacy the fact that the Labour Party had been in opposition in the House of Commons for almost two decades, and it is not difficult to understand why this party committed itself to a programme of devolution if it were elected to power. This happened in 1997. Once in office, Tony Blair’s New Labour began a significant and wide-ranging programme of constitutional change, one outcome of which was the creation of the National Assembly for Wales (NAW) in 1999. The next section outlines how these changes came about, and provides an overview of the main powers of the National Assembly for Wales.