In 2000/01, 79% of waste collected from English households was disposed of at landfill with only 12% recycled. By 2013/14, landfill had fallen to 31% and rates of recycling had increased to 43%. Such statistics reveal a dramatic shift in the management of household waste. Consumers across England have been called upon to separate, to wash and to squash their paper, plastics and cardboard from the rest of the waste they throw into their black bag. By sorting this waste for recycling, consumers perform vital and unpaid work which is crucial to the operation of waste management systems.

Recycling provides just one example of a larger trend in which consumers are expected to carry out unpaid work in order to consume or dispose of goods and services. You will likely be familiar with self-service in supermarkets, with online checking-in and with self-assembly equipment. The growth of the internet has introduced new kinds of work for consumers, like booking holidays or managing finances online. Consumption work is growing and yet little academic attention has focused upon this. Consumers make an important contribution to economic processes and the work they do interacts with other types of work conducted in the public, private, and voluntary sectors.

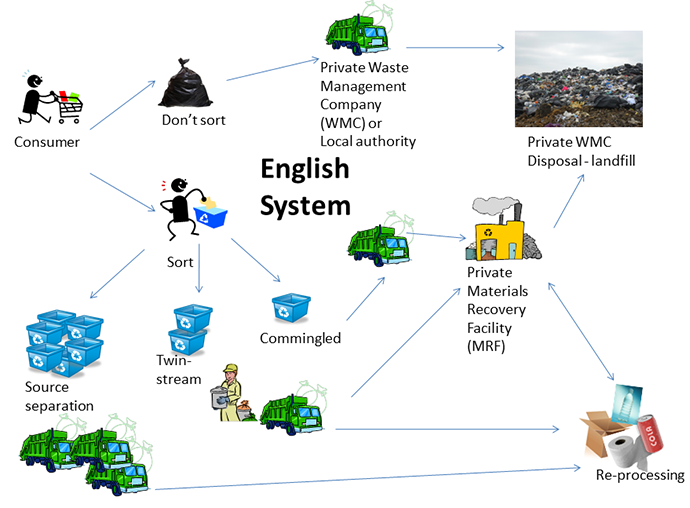

In the case of waste management, placing all waste into a black bag (e.g. not sorting it for recycling) implicates the consumer in one chain of processes, whereas separating the waste for recycling involves the consumer in a very different chain of processes. The journey of waste from household to disposal/re-use is summarised in the diagram below.

When waste is placed into a black bag, it is usually collected by the local authority or their contracted representative and deposited at a private waste management company landfill site for which a £80 per /tonne tax is imposed in addition to a gate fee. This is a very expensive route for the local authority and it is for this reason (as well as EU legislation) that alternatives, like incineration and mechanical biological treatment plants (for disposal) and recycling systems have been developed. Recycling offers local authorities the opportunity to save on the landfill taxes and (sometimes) benefit from the sale of materials.

But decisions about how to sort or whether to sort are not always straightforward. Because of the way that recycling systems developed in England, there is a great deal of variation between local authorities, both in terms of what is collected and how it should be sorted. Some councils expect consumers to sort into multiple bags, boxes and bins, whilst others place all their recyclables into one bag/bin. When the consumer sorts their waste into different fractions, this can be delivered to a reprocessing plant and local authorities generally receive good returns on the sale of this source-separated material. Comingled, or mixed, recyclables, on the other hand, need to be sorted into separate fractions before they can be reprocessed. Materials Recovery Facilities (MRFs) sort mixed recyclables through technological and labour-intensive systems and local authorities have to pay to use them. Whether they benefit from the sale of the processed materials depends on the terms of contract they have with the private company. Twin-stream systems offer a compromise, with the consumer doing a basic sort into two boxes and collection operatives then sorting the waste into specialist vehicles at the kerbside or at a MRF. All of these systems rely on different degrees of consumer labour and relate to the value that can be generated from the waste.

With so much variation, it is not surprising that consumers sometimes struggle to know what is and isn’t recyclable. Listen to the extract below, in which a couple discuss the difficulties they have in identifying whether a plastic bag that surrounds a batch of apples is recyclable.

Getting it wrong does have implications for the processes that follow, to a greater and lesser degree. For example, stones caught up in glass reprocessing systems can create imperfections when melting down, and the wrong type of plastic delivered to a MRF unable to process it can result in contamination. Whereas, metal is less susceptible to consumer error.

With the EU Waste Framework Directive calling on all member states to reach a 50 per cent household recycling rate and halve the waste it sends to landfill by 2020, it is clear that the work of consumers will continue to be crucial for the success of the waste management sector.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews